Andi Sudjana PUTRA

Dean’s Office, College of Design & Engineering (CDE)

Andi explores how the purposeful use of learning spaces in his project-based design module can enhance student learning.

Putra, A. S. (2022, Sept 28). A reflection on classroom layouts in a design class. Teaching Connections. https://blog.nus.edu.sg/teachingconnections/2022/09/28/a-reflection-on-classroom-layouts-in-a-design-class/

Classroom Layout in Design Engineering Education

The impact of classroom layouts to students’ learning experience has been the subject of a number of studies (e.g., Barrett et al., 2015; Strickland & Kapitula, 2014). These studies conclude that designing classroom layouts intentionally provide more effective teaching and learning across multiple outcomes, such as creativity, motivation, engagement, achievements and learning progress. For example, Rands and Gansemer-Topf (2017) investigated how a redesigned active learning classroom (with moveable chairs, portable whiteboards, tables for group work) affords learning behaviours and teaching practices. They found that the open classroom design fostered a greater sense of community and provided more flexibility for teacher-student and student-student interactions.

To explore the purposeful use of learning spaces, I decided to adopt a more flexible and open learning environment in my project-based design module, EG2201A “User-centred Collaborative Design”, by providing moveable furniture, and allowing students greater freedom to position themselves physically during the group discussion. I further conceptualised the students’ design learning activities in relation to Problem Space (involves discovery and definition) and Solution Space (involves development and delivery) (Tschimmel, 2012, see Figure 1 and Appendix for a description) and observed how learning spaces promote or hinder these activities. In the following paragraphs, I share my observations about three common layouts, and the way students responded and interacted in these spaces.

Classroom Layouts

A. Instructor-centric Layout

Prior to designing, students clarified what they needed to do with the instructor. The classroom layout is depicted in Figure 2.

The following observations were made:

- Students’ gaze: Towards the instructor

- Students’ actions: Minimal, such as annotating or note-taking

- Instructor’s engagement: Dominant

This layout is effective for conveying information from the instructor to students. To enhance student engagement in this layout, the instructor needs to gradually step back and allow students to take charge of their learning.

B. Student-centric Layout in Problem Space

In the Problem Space, students work on abstract concepts such as insights. The classroom layout is depicted in Figure 3.

It can be observed that:

- Students’ gaze: Towards other students and their own digital devices.

- Students’ actions: Towards their own digital devices, for example a laptop or a tablet, as the avenue to access a shared virtual working space.

- Instructor’s engagement: Facilitates students’ learning but does not interfere in their learning.

This layout is effective for intangible collaboration among students. The instructor needs to regularly check in on students’ progress, despite the work on virtual space, to provide timely guidance.

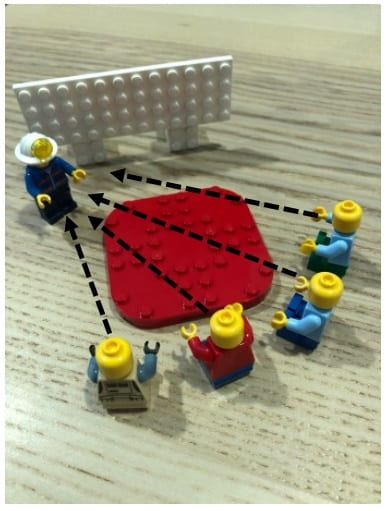

C. Student-centric Layout in Solution Space

In the Solution Space, students work on concrete prototypes. The classroom layout is as depicted in Figure 4.

It can be observed that:

- Students’ gaze: Towards other students and towards the shared objects (e.g. a prototype).

- Students’ actions: Towards the shared objects.

- Instructor’s engagement: Facilitates students’ learning but does not interfere in their learning.

This layout is effective for tangible collaboration among students. Students are mostly independent in their learning.

My observations thus far are preliminary and qualitative, but consistent throughout the class. The design of different learning spaces may promote or constrain students’ active interactions. Therefore, there is a need for teachers to carefully consider the learning spaces and environment when engaging students in active learning.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the teaching team of EG2201A: Dr. Tang Kok Zuea, Ms. Lee Hyun Ju, Mr. Lim Shi-Chong, Ms. Sarupraba D/O Arjunan, and Mr. Pok Ruey Jye.

References

Barrett, P., Davies, F., Zhang, Y., & Barrett, L. (2015). The impact of classroom design on pupils’ learning: Final results of a holistic, multi-level analysis. Building and Environment, 89, 118-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2015.02.013

Rands, M. L., & Gansemer-Topf, A. M. (2017). The room itself is active: How classroom design impacts student engagement. Journal of Learning Spaces, 6(1), 26-33.

Stricklan, A., & Kapitula, L. R. (2014, June 14). How classroom design affects student engagement. Steelcase Education, 1-6.

Eder, W. E. (2005). Survey of pedagogics applicable to design education: An English-language viewpoint. International Journal of Engineering Education, 21(3), 480-501.

Tschimmel, K. (2012). Design thinking as an effective toolkit for innovation. In: Proceedings of the XXIII ISPIM Conference: Action for Innovation: Innovating from Experience. Barcelona. ISBN 978-952-265-243-0.

Appendix. Double Diamond Framework

- The Double Diamond design methodology, developed by the UK Design Council, consists of four stages of: (1) Discover, (2) Define, (3) Develop, and (4) Deliver.

- Discover is the stage where designers are searching for new opportunities, markets, trends and insights.

- Define is the stage where designers distil information from the Discover stage to formulate the design project, including its project development and project management.

- In the Develop stage, designers iteratively develop and test solutions.

- In the Deliver stage, designers take through the polished concept into production and launching.

About the Author

|

Andi Sudjana PUTRA is a Senior Lecturer in the Innovation and Design Programme (iDP), College of Design and Engineering (CDE). He has been teaching design and engineering to students and professionals for more than 10 years. His expertise is in mechatronics design. His designs have been applied in healthcare and community settings. Andi can be contacted at andi_sp@nus.edu.sg. |