CHAN Taw Kuei

Department of Physics, Faculty of Science (FoS)

Taw Kuei discusses how the shift from face-to-face to remote learning has made an impact on students’ academic workload, and what educators can do to address these issues and offer support.

Chan T. K. (2021, Aug 27). Student academic workload during the COVID-19 pandemic. Teaching Connections. https://blog.nus.edu.sg/teachingconnections/2021/08/27/student-academic…ovid-19-pandemic/.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced most teaching and learning to be conducted remotely over online platforms. A common teaching practice adopted during the pandemic is a 100% continual assessment (CA) structure, where face-to-face final examinations are replaced with multiple learning tasks such as quizzes and assignments. These learning tasks may be designed as enquiry-based learning, which require a sustained effort at group discussions, literature review, designing, content creation, and writing. With the pandemic forcing almost all modules into remote learning simultaneously, many students were suddenly swamped with many time-consuming online learning tasks along with a long chain of deadlines throughout the semester.

Many students may encounter difficulties handling this deluge of tasks expected of them, and may go into “survival mode” where their focus is no longer in engaging in meaningful learning, but in performing the bare minimum of work to meet the next deadline. This adversely impacts the quality of learning, as students operating in this mode may adopt the surface learning approach (Biggs & Tang, 2011, p. 25) as a coping mechanism to manage their workload. Some may become discouraged and disillusioned, resulting in a severe reduction in the situation-specific state of motivation to learn (Brophy, 2010, p. 12). With the new normal of remote and hybrid learning, we should consider the level of academic workload students face and its impact on their learning behavior and the quality of their learning.

Personally, I have observed and also received feedback in my courses over the last year that highlight the heavy CA workload students experience, such as:

- Experiencing difficulties in organising group discussions over Zoom,

- Forgetting to attempt online quizzes,

- Facing back-to-back and conflicting deadlines across multiple modules,

- Facing increased workload during certain weeks of the semester,

- Seeking extensions for submission deadlines,

- Completely giving up and not submitting the assignments at all.

While students that report such difficulties may form the minority, our considerations should extend to them as well, to ensure that no student is left behind.

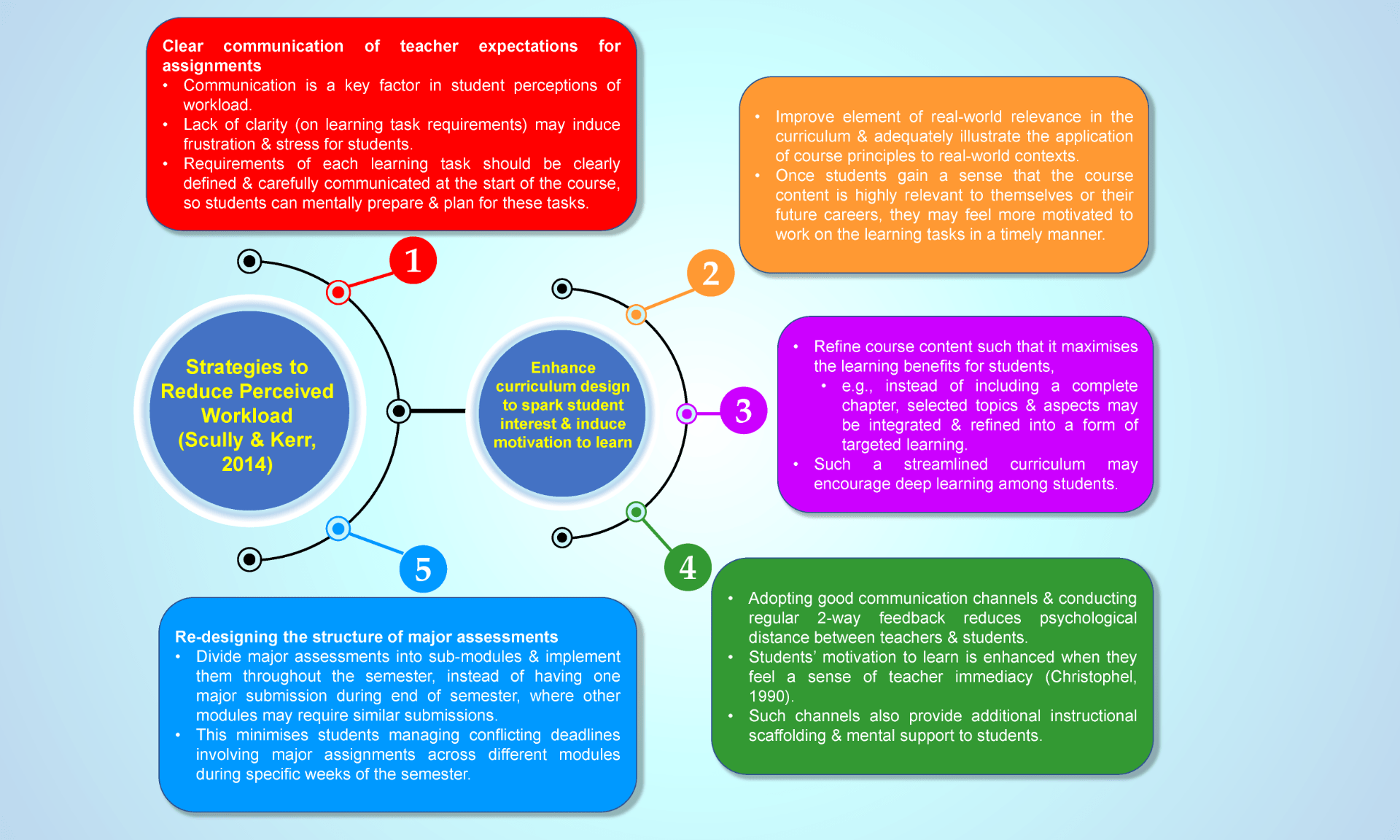

As instructors, we design our learning tasks and module structure based on a set of intended learning outcomes and we envision how students are to achieve these outcomes. We implicitly understand the actual workload and task complexity in our design. However, there may be a disconnect between our intended designs and student perceptions. Students come into each course with a wide spectrum of time management skills and motivation to learn. Given a set of tasks, students perceive the involved workload differently. When faced with a heavy perceived workload, students may no longer engage in the learning activities in the intended manner. Scully and Kerr (2014) provided a few strategies to reduce the perceived workload (Figure 1):

Students may also be encouraged to adopt good time management practices to manage their workload. Indeed, Häfner et al. (2015) observed in their study that students who attended a time management training programme reported significantly lower perceived stress and higher perceived control of their time. While it is not feasible to provide time management training in every module, instructors may encourage good time management behaviours by sending regular reminders for learning tasks, not only for final submission of the completed work, but also for the timely embarkation of each learning task. In addition, emphasising the importance and relevance of each learning task and carefully illustrating how each task is aligned with the module’s intended learning outcomes, may motivate students to work on the tasks early and reduce procrastination.

As the pandemic wears on with no immediate end in the horizon, educators have to be cognisant of the unintended effects of the universal shift into remote learning on students’ perception of workload and stress. The carrying over of pre-pandemic practices into today’s pandemic era may have a significant role in causing students to face conflicting deadlines, especially during periods within the semester where such deadlines are customarily set. For example, midterm tests traditionally take place during instructional Weeks 7 to 8, followed by submission deadlines for major assignments and projects. It is perhaps time to consider a paradigm shift in our design and traditional implementation of learning tasks to an assessment model that is closer to the spirit of continual assessment, where learning tasks are spread over the semester and assessments are administered continually in a progressive manner in multiple, smaller stages, instead of assessing discrete, major pieces of work or events. This is an important consideration for us educators while we continue to ensure students have a positive learning experience, maintain their mental wellbeing and their motivation to learn.

|

CHAN Taw Kuei is a senior lecturer at the NUS Department of Physics. He began teaching at the Department in 2010 and joined as a lecturer in 2013. His research interests include authentic and experiential learning, teacher immediacy, as well as theories of motivation in education psychology. Taw Kuei can be reached at phyctk@nus.edu.sg. |

References

Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University (4th Ed.). New York: Open University Press.

Brophy, J. (2010). Motivating Students to Learn (3rd Ed.). New York: Routledge.

Christophel, M. C. (1990). The relationships among teacher immediacy behaviors, student motivation, and learning, Communication Education, 39(4), 323-340. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529009378813

Häfner, A., Stock, A., & Oberst, V. (2015). Decreasing students’ stress through time management training: an intervention study. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30(1), 81-94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-014-0229-2

Scully, G., & Kerr, R. (2014). Student workload and assessment: Strategies to manage expectations and inform curriculum development. Accounting Education, 23(5), 443-466. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2014.947094