Susan LEE

Centre for English Language Communication (CELC)

In a situated learning environment, Susan considers how to further challenge students to become more deliberate in their application of interpersonal communication skills through practice, observation, and reflection.

Recommended Citation Lee, S. (2021, May 19). Cultivating the deliberate learner and practitioner. Teaching Connections. https://blog.nus.edu.sg/teachingconnections/2021/05/19/cultivating-the-deliberate-learner-and-practitioner/

The module ES2007D “Professional Communication”, customised for students from the Department of Real Estate, adopts situated learning principles (McLellan, 1996) in its iteration of tasks and assignments to create a learning environment that simulates workplace reality.

This practice is examined by Trede and McEwen (2016), which suggests a need for “academic redesigns that prepare learners as deliberate professionals” (Boud, 2016, p. 157) to address the “risk that students will be trapped in current knowledge without the capacity to move beyond what they have been taught” (p. 158). Authors advocate for “curricula spaces for deliberative thinking and deliberate action(s) (that) have an impact on the nature of knowledge and types of learning that students experience” (Harland, 2016, p. 175).

To enable students to apply their learning experience beyond the classroom, ES2007D designs immersive skills practices in teaching interpersonal communication skills for interest-based negotiation. Interest-based negotiations focus on collaborative problem-solving to achieve an outcome that best satisfies both parties’ needs and concerns. In contrast, positional negotiation works on gaining a win-lose outcome or a weak compromise where both parties give up part of their needs.

Evoking Imagination

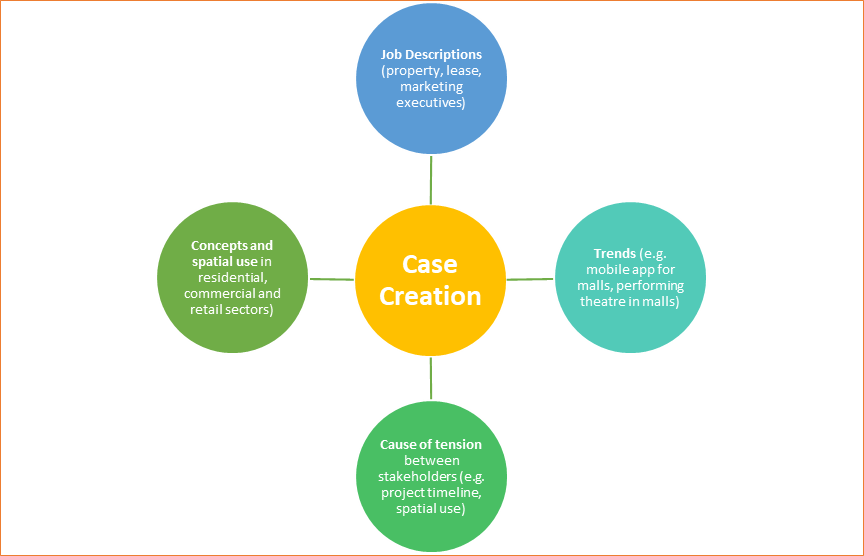

To develop negotiation cases that mirror authentic workplace exchanges (Herrington & Herrington, 2006), I researched industry trends and job descriptions for a realistic representation of issues (Figure 1). An example of a negotiation case is provided in the Appendix.

Tutors and students have found the cases imaginative and rich. The case discussions have brought unexpected incidental learning (McLaughlin, 1965), as students shared informal feedback on applying the skills in their work in start-ups and real estate sales. In the module feedback, students said the cases “provided essential real-life scenarios”, “permit(ted) creativity and exploration of ideas,” and honed their skills on “how to facilitate effective communication”.

Immersing in Roles

To circumvent the risk of ‘trapping’ students in the safety nest of classroom learning, Boud (2016) lists professional practices that consider two factors: learner environment and learner management (p. 170).

The construct of skills practice places students in the roles of executives in work teams. Each negotiation team is given a case scenario that functions like a task brief. The case informs them of their roles, issues, and interests. The teams have 20 minutes to read and discuss the case scenario before proceeding to meet their counterparts for a 20-minute negotiation.

The mission to negotiate creates a tense learner environment with time constraints and limited information, which heightens authenticity. Students experience the pressure of preparing for a negotiation, engaging in active listening, and responding with spontaneity, especially when new information is shared at the meeting.

After the first skills practice, some students reflected that they felt lost or ill-prepared during the negotiation. It takes one to two practice rounds with peer observations and feedback before they learn to read the case more closely, anticipate possible directions, face unexpected counterparts’ input calmly, and present their interests systematically. The “practice–reflect–observe–practice” structure adopts Kolb’s cycle of experiential learning (1984). Students’ feedback showed that they liked the “hands-on learning, (with)many opportunities to try” (Figure 2).

Facilitating Deliberate Learning

To ensure consistency in learner management, tutors’ facilitation notes emphasise the debrief approach. The tutor facilitates a student-centred feedback session which requires peer observers to highlight good practices and suggest improvements. After which, tutor adds insights and identifies gaps or exemplary actions specific to each role-play. The facilitation approach simulates workplace discussions between colleagues and mentors while minimising unilateral learning from tutors as insights are sourced from the students’ own examples and observations.

The tutor also focuses on specific aspects of observations made over the three sessions, using different cases to progressively challenge students to apply higher-order skills with more depth. For instance, most students are competent in rapport-building and summarising, but many lack the adroitness to stage a negotiation, ask purposeful questions, and moderate levels of assertiveness.

Motivating Deliberate Practice

Using negotiation cases with authentic details greatly enhanced students’ skills application in ES2007D (Figure 3). Firstly, they could relate to the context and issues readily. Secondly, as students perceived each role-play as competitive sparring, they were eager to execute the negotiation communication strategies they acquired through the flipped format (Strayer, 2012), like rules from a playbook. Evidently, students were motivated to demonstrate and hone their skills throughout the sessions. Thirdly, students became keen commentators on their peers’ role-plays as they had worked on the same cases. Looking ahead, I would consider engaging students to develop cases in subsequent iterations of the module, as much can be learnt from the process.

|

Susan LEE is a Lecturer in CELC. She has taught English communication for 20 years at institutions and with adult learners in corporate environment. She is ACTA certified (WSQ Advanced Certificate in Training and Assessment) and passionate in customising learning to engage skill application in contexts for presentation, interpersonal communication and negotiation. Susan can be reached at elclmss@nus.edu.sg |

References

Boud, D. (2016) Taking professional practice seriously: Implications for deliberate course design. In F. Trede, & C. McEwen (Eds), Educating the deliberate professional: Preparing for future practices. Professional and Practice-based Learning, 17. Springer, Cham. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32958-1_11

Harland, T. (2016) Deliberate subversion of time: Slow scholarship and learning through research. In F. Trede, & C. McEwen (Eds), Educating the deliberate professional: Preparing for future practices. Professional and Practice-based Learning, 17. Springer, Cham. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32958-1_12

Herrington, A., & Herrington, J. (Eds.). (2006). Authentic learning environments in higher education. Hershey, PA: Information Science Publishing.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

McLaughlin, B. (1965). “Intentional” and “incidental” learning in human subjects. The role of instructions to learn and motivation. Psychol. Bull. 63, 359–376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0021759

McLellan, H. (Ed.). (1996). Situated learning perspectives. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Strayer, J. F. (2012). How learning in an inverted classroom influences cooperation, innovation and task orientation. Learning Environments Research, 15(2), 171–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-012-9108-4

Trede, F., & McEwen, C. (Eds.). (2016). Educating the deliberate professional: Preparing for future practices. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32958-1

Appendix

Here is an example of a negotiation case. A video of the negotiation can be viewed here.

Scenario A

You are the corporate social responsibility (CSR) team planning the project to commemorate DRE Holdings’ role in creating homes and heritage. CSR is a significant aspect of DRE Holdings’ core values. The Public Relations (PR) team has advised your team on associating our brand with CSR efforts strategically.

Your team is proposing a virtual gallery that exhibits evidence of growth and changes brought by DRE Holdings. The gallery will include write-ups of the early DRE Holdings’ retail and residential properties in matured estates. You plan to interview and film about 30 older residents on their memories of living in these estates. The residents’ voices will enliven the exhibition in an authentic way and draw media interest.

Archived photographs of award-winning DRE Holdings properties in the matured estates, maps, and news articles about the developments will be exhibited. The nostalgic display will highlight DRE Holdings’ history alongside Singapore’s. Your team is confident that the heritage gallery will be impactful in showcasing the role of real estate in creating home and heritage, with DRE Holdings in the heart of it. This approach has worked recently during the Singapore Heritage Festival online exhibition which showcased short videos of heritage districts, local food, and award-winning architecture.

You know the project will enhance DRE Holdings’ reputation as a community-centred developer. Your team will present the ideas to Director, Social Impact and Sustainability next week. The Public Relations (PR) team, however, has advised you to showcase DRE Holdings’ reputation as the industry leader. They suggest focusing on newer properties and highlighting our heritage in building high-tech, innovative sustainable developments.

Your team feels that the PR team is pragmatic and the focus makes the project seem insincere. The PR team has asked to meet your team to advise on the project before the presentation.

Scenario B

You are the Public Relations (PR) team and advises all Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) efforts. The CSR project team is working on a project to commemorate DRE Holdings’ role in creating home and heritage. CSR is a significant aspect of DRE Holdings’ branding and core values. A Deloitte survey found that 70 percent of millennials considered a company’s commitment to social responsibility during job searches.

The CSR team is planning a virtual gallery that exhibits growth and changes brought by DRE Holdings. The exhibition will feature DRE Holdings’ retail and residential developments in matured estates. The team plans to interview about 30 older residents from these developments, inviting them to share their memories of these estates. The gallery will also showcase archived photographs, maps, and news articles on DRE Holdings’ projects in these estates. The team will present their ideas to Director, Social Impact, and Sustainability next week.

Your team feels that their idea is unambitious and unoriginal. You have advised them to focus the long-term goals of building sustainable developments using cutting-edge innovation. The angle of creating a heritage through sustainable innovations will enhance our brand as an industry leader. The future-looking stance will also draw the attention of socially conscious young talents.

Besides, the virtual gallery is likely to draw interest of young viewers. Nostalgia is not the most appealing way to engage them. Good camera angles and points of view are critical for online gallery viewing. Footages of old buildings and 30 interviews will not be interesting. Instead, videos showing construction technology and the process behind the creations of architectural designs will suit the online platform much better.

Your team is certain that more can be done to leverage this project for publicity. You have planned a meeting to advise the team before their presentation.