TOH Tai Chong

College of Alice & Peter Tan (CAPT)

Tai Chong talks about the importance and benefits of educators developing and maintaining student partnerships in teaching and learning

Students-as-Partners: An emerging pedagogy in higher education

In higher education, there has been a recent push for educators to strengthen staff-student partnerships and co-create learning opportunities in and out of the classroom.

At the core of this pedagogy is a reframing of educators’ mindset.

Students-as-Partners (SaP) pedagogy places a strong emphasis on staff-student collaboration (Matthews, Dwyer, Hine, & Turner, 2018) to provide opportunities for all participants to contribute to the learning activity, such as conceptualisation, implementation, and evaluation (Cook-Sather, Bovill, & Felten, 2014).

Since 2014, a significant body of research has critically examined the pedagogical benefits of SaP and quickly grown into a worldwide movement, sprouting SaP networks among universities in the US, UK and Australia.

In the Residential College (RC) where I teach, staff-student partnerships are an integral part of our living and learning programme. From inter-disciplinary research to student symposiums and interest groups, college staff spend a significant amount of time collaborating on these activities.

So why should educators strengthen our partnership with students in teaching and learning? Here are my three most compelling reasons, derived from teaching experience and scholarship.

Reason 1: Development of new applications and teaching activities

Teaching in an interdisciplinary environment poses significant challenges to many of us who are trained as specialists as it requires us to teach disciplines outside our own. However, it also presents unique opportunities to learn from a diverse team of academics and students (Toh & Ortiga, 2018).

In 2018, I collaborated with a psychology undergraduate to research on the social value of coastal parks in Singapore. As a marine biologist working on a social science topic for the first time, my initial plan was to interview park-goers and elucidate the emerging themes. The student suggested applying the Schwartz Value, a concept in psychology, and he was proactive in developing and implementing the surveys.

The student reflected that integrating marine sciences and psychology has “broadened his perspectives” of how these two disciplines could be synergised, and he was excited to apply “a different dimension to the understanding of the whole issue”. While I am used to leading disciplinary research, this partnership has created a platform to pilot new interdisciplinary research applications and teaching activities.

Reason 2: Increased student engagement

Research in SaP pedagogy has also demonstrated an increase in student engagement and staff-student rapport (Mercer-Mapstone et al., 2017), which are in turn, contributing factors to learning gain (Umbach & Wawrzynski, 2005).

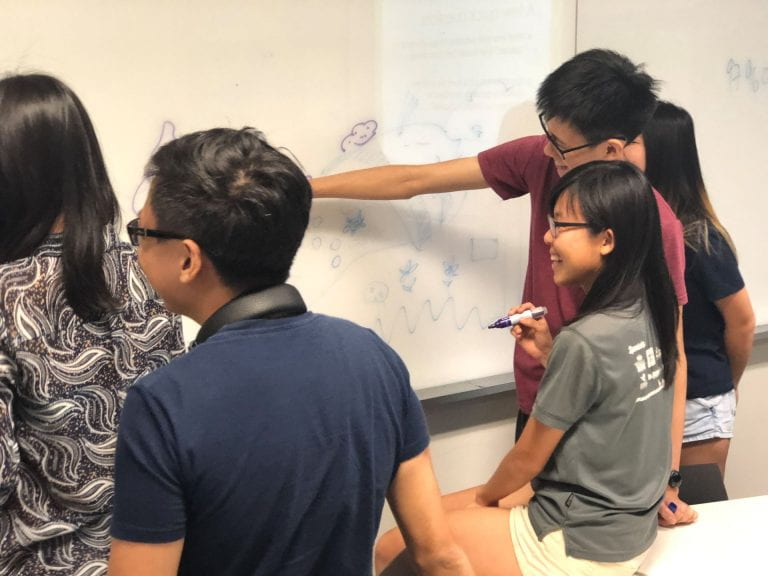

I have experimented with SaP in my classroom through teaching activities such as self-directed field trips where students decide where they would like to go for their group assignments.

To be effective, such activities should have a broad scope and clear objectives, supplemented with consistent formative feedback throughout the semester. As the students refine their tasks, they also share areas of concern and I provide targeted feedback to support their learning.

Photo courtesy of TOH Tai Chong

In my post-module surveys, students indicated they enjoyed this activity because of its high levels of ownership and engagement, and consistently rated its learning value above 4.6 (out of 5).

Reason 3: Greater support for student learning

Beyond a pedagogical tool, SaP presents a fundamental shift in how we perceive students’ role in learning (Matthews, 2017). The recent COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted our teaching, but also presents an opportunity to involve students as partners in education.

My engagement with my students have uncovered diverse factors that affect their learning and this process have helped put in place timely instructional interventions, especially this semester. Students facing structural constraints (e.g. multiple deadlines and lack of conducive study spaces) can be supported readily, but students impacted by social or mental health issues will need more coordinated support.

Photo courtesy of TOH Tai Chong

Even student leaders are not spared. I have spoken to a few who thought it was impossible to plan any meaningful activities and felt ‘jaded’ in their leadership capacity. In my RC, we have a system of ‘integrated student care and support’ where the teachers, residential and administrative staff partner student leaders to create conducive living and learning environments. Without staff-student partnership, one can imagine the impact on our students’ well-being and learning.

Concluding remarks

As my student aptly puts it, “you cannot use tech as a hammer and find nails to hit”. Similarly, SaP cannot be applied for all learning activities without first considering the context. We can apply SaP in a variety of learning activities but it should always be aligned to the programme’s intended learning outcomes.

|

TOH Tai Chong is a Senior Lecturer at the College of Alice & Peter Tan (CAPT), where he is also the Associate Director of Studies and Academic Director. He believes that learning should be integrated across disciplines and learning activities. Hence, his interests in education include Students-as-Partners (SaP), experiential learning, reflective writing and interdisciplinary education. Tai Chong can be reached at taichong.toh@nus.edu.sg. |

References

Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C., & Felten, P. (2014). Engaging students as partners in learning and teaching: A guide for faculty. John Wiley & Sons.

Matthews, K. E. (2017). Five propositions for genuine students as partners practice. International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i2.3315

Matthews, K. E., Dwyer, A., Hine, L., & Turner, J. (2018). Conceptions of students as partners. Higher Education, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0257-y

Matthews, K. E. (2019). Rethinking the problem of faculty resistance to engaging with students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2019.130202

Mercer-Mapstone, L., Dvorakova, S. L., Matthews, K. E., Abbot, S., Cheng, B., Felten, P., … & Swaim, K. (2017). A systematic literature review of students as partners in higher education. International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3119

Toh, T.C. From specialist to teacher-scholar: The influence of SoTL on the journey of an early career academic (in review)

Toh, T. C., & Ortiga, Y. (2018). Reflection of an interdisciplinary team teaching experience. Asian Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 8(2), 78-89. Retrieved from http://nus.edu.sg/cdtl/engagement/publications/ajsotl-home/archive-of-past-issues/v8n2/a-reflection-on-interdisciplinary-team-teaching-in-a-residential-college.

Umbach, P. D., & Wawrzynski, M. R. (2005). Faculty do matter: The role of college faculty in student learning and engagement. Research in Higher education, 46(2), 153-184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-004-1598-1