Anita TOH

Centre for English Language Communication (CELC)

Anita takes us through her attempt to scaffold and enhance participation in her class using Poll Everywhere, starting from low-risk MCQs to open-class discussions.

Image by storyset on Freepik

Toh, A. (2023, November 23). Scaffolding student participation with Poll Everywhere. Teaching Connections. https://blog.nus.edu.sg/teachingconnections/2023/11/23/scaffolding-student-participation-with-poll-everywhere/

Large classes offer a valuable opportunity to tap on the diversity of students’ perspectives (Dekker, 2020), yet large classes can also be intimidating and deter some students from speaking up and sharing their views (Aisha & Mulyana, 2019; Aslan & Şahin, 2020). This was the challenge I faced with a group of 50 third-year undergraduate students in the course EE3031 “Innovation and Enterprise I”. The challenge was to stimulate interaction and open discussion among the students.

This essay reflects on my attempt to leverage Poll Everywhere1 to scaffold participation in this large class, beginning with low-risk multiple-choice questions (MCQs) and culminating in a self-directed open class discussion. Scaffolding involves providing support to students as they learn new concepts, skills, and behaviours. Scaffolding is often gradually withdrawn as students become more competent or comfortable with the new concepts, skills, or behaviours (Gonulal & Loewen, 2018).

From One-way Online Responses to Self-directed Open Class Discussion

The goal was to foster active class discussions between the students and myself, and among their peers in class. To accomplish this, I began by using Poll Everywhere to create a safe low-risk environment for the students to start contributing (Filer, 2010). Gradually, the interaction transitioned from online participation to in-person responses and conversations.

The stages of these interactions during the session are as follows:

Stage 1: One-way online response

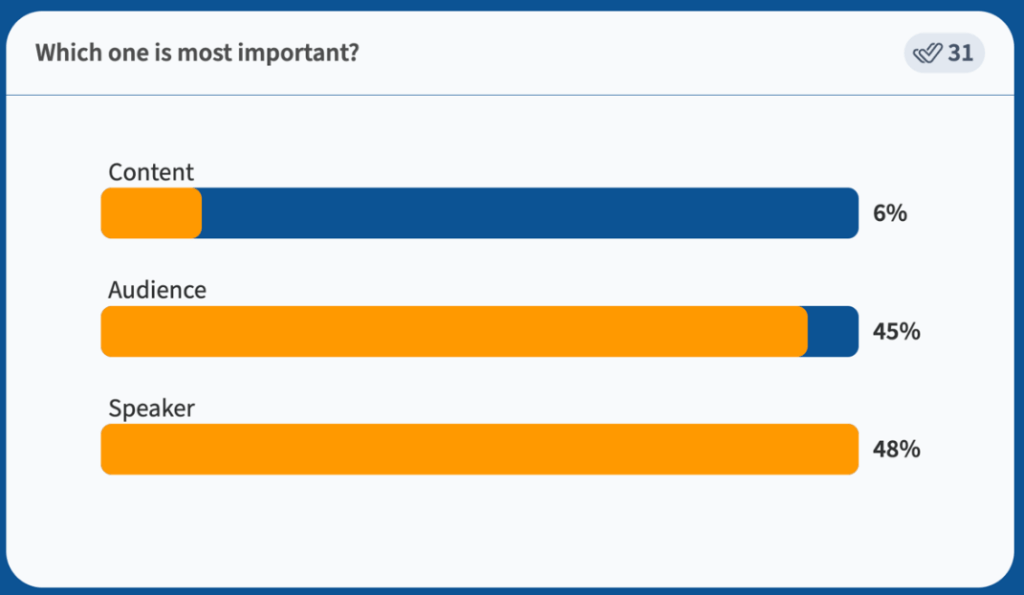

The session began with a Poll Everywhere MCQ with live results shared with the class (Figure 1). I validated each selection, then shared expert presenter best practices.

Stage 2: Two-way online-in-person responses

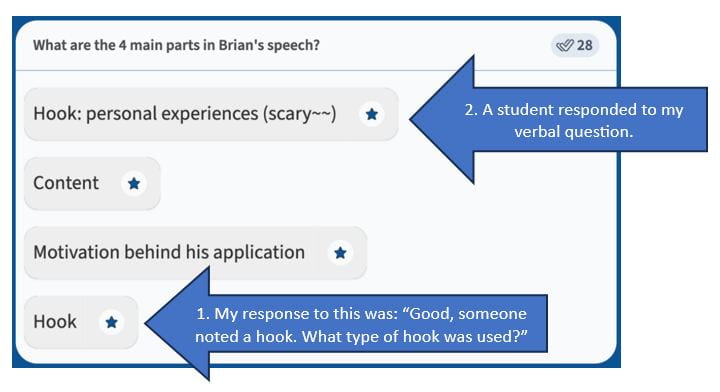

The students watched a short pitch presentation video and responded to a Poll Everywhere short answer question (Figure 2). Again, responses were shared live and I validated them. In addition, this time, as their answers appeared on the screen, I followed up with probing questions like, “Someone noted a hook. What type of hook was used specifically?” Figure 2 shows an example of a student’s response to this question.

Figure 2. A screenshot of Poll Everywhere short answer responses showing an example of a student’s online response to my in-person verbal question.

Stage 3: In-person non-verbal response

The students watched another pitch presentation video and were asked to raise their hands if they thought the presenter conveyed a strong stage presence. This marked the shift from online to in-person responses, albeit non-verbally (and therefore still relatively low risk) at this stage.

Stage 4: In-person verbal response

To the students who raised their hands, I asked what non-verbal cues were used by the speaker to convey a strong stage presence. This further transitioned the class towards in-person verbal responses. By this point, many students seemed quite willing to verbally share their ideas.

Stage 5: Whole class open discussion

Finally, I asked the class what made the speaker sound conversational, as opposed to sounding scripted and unnatural. This time I waited for the students to voluntarily share their views. One of the students who had been responding throughout hazarded an answer. I acknowledged his answer and asked another student whether he agreed. When the second student offered a different viewpoint, I went back to the first student and asked his response. At this stage, I was calling on students randomly and they readily responded. Eventually, more students spoke up and got involved in the discussion voluntarily without any prompting from me. By the end of the session, I could take a step back and allowed the students to freely converse with each other. Although not all the 50 students spoke up, there was a lot more interaction than I could had expected without the intentional scaffolding.

Students’ feedback about the session was positive:

- “Engaging lectures with use of anonymous reply platforms (PollEv) which allowed shy students to engage in the class also.”

- “She engages the class so it’s not boring.”

In conclusion, Poll Everywhere’s anonymity has allowed me to create a safe space for student participation. Its real-time feedback has allowed me to tailor my teaching to the students’ responses, improving the lesson’s relevance to the students’ perspectives. In future lessons, I would like to include an anonymous Poll Everywhere question board for student questions throughout the lesson. This would provide an additional risk-free platform for them to “speak up”, enable me to respond to their concerns, and further improve the engagement and relevance of the lesson.

Endnote

- Check out the wiki page on Poll Everywhere [by the Centre for Instructional Technology (CIT)] for more information on how you can apply this classroom response system in your courses.

References

Aisha, S., & Mulyana, D. (2019). Indonesian postgraduate students’ intercultural communication experiences in the United Kingdom. Jurnal Kajian Komunikasi, 7(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.24198/jkk.v7i1.20901

Aslan, R., & Şahin, M. (2020). ‘I feel like I go blank’: Identifying the factors affecting classroom participation in an oral communication course. TEFLIN Journal – A Publication on the Teaching and Learning of English, 31(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.15639/teflinjournal.v31i1/19-43

Dekker, T. J. (2020). Teaching critical thinking through engagement with multiplicity. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 37, 100701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100701

Filer, D. (2010). Everyone’s answering: Using technology to increase classroom participation. Nurs Educ Perspect, 31(4), 247-50. PMID: 20882867. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20882867/

Gonulal, T., & Loewen, S. (2018). Scaffolding technique. In J. I. Liontas, T. International Association, & M. DelliCarpini (Eds.), The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching (pp. 1–5). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0180

|

Anita TOH is a lecturer at the Centre for English Language Communication (CELC) at the National University of Singapore, with an interest in leveraging technology to enhance teaching and learning. Her projects include improving online independent learning engagement using branching scenarios and MCQs, and investigating the impact of different video presentation formats on student engagement and performance. Anita can be reached at elcatal@nus.edu.sg. |