Katrina TAN

NUS Futures Office

Office of the President

From March to October 2023, the NUS Futures Office ran eight workshops for the NUS community and its stakeholders to talk about discourse. We spoke to academics, executive staff, local and foreign students, and public servants, asking how trends would impact public discourse and higher education. To encourage candid and open discussion, all workshops were held under Chatham House Rule1. Building on earlier work, this post highlights themes and questions that emerged from the three workshops with NUS academics – not to criticise or advocate, but to continue the dialogue.

Photo courtesy of NUS Image Bank

Tan, K. P. C. (2024, February 26). Trends in public discourse: Opportunities and challenges in higher education. Teaching Connections. https://blog.nus.edu.sg/teachingconnections/2024/02/26/trends-in-public-discourse-opportunities-and-challenges-in-higher-education/

About the Workshops

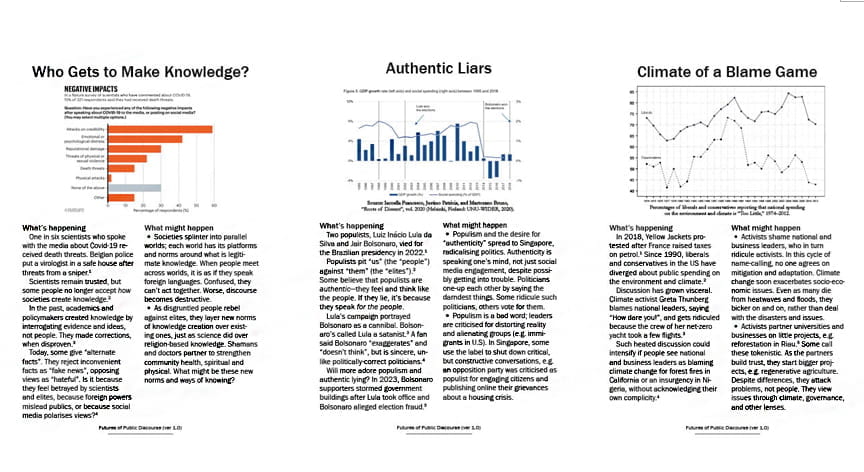

During the workshops, the NUS Futures Office used trends it had researched and presented as cards (see Figure 1 for the excerpts) as conversation triggers: what are the possible futures of public discourse in the light of such trends, and what are the implications for higher education in NUS?

Figure 1. A selection of some of the cards we used as conversation starters

(Click on Figure 1 or this link to browse through the full deck of cards)

Themes and Questions That Emerged

We had seen public discourse as a discrete subject, impacting the skills educators need to cultivate dialogue, for example. We learnt from the workshops that how NUS responds to changes in public discourse is tied up with who we are and how we educate.

Who we are

As NUS is a microcosm of the larger society in Singapore, trends like the loss of the ability to dialogue, the privileging of online over physical interaction, the fear of missing out and hyper-competition, etc. are entrenched and reinforced outside NUS. Hence, to overcome these forces, there is a need for us to engage students outside campus as well. We might need to go to where they hang out, and leverage their experiences outside NUS to enhance their learning inside it. This way, the connection between school and real life is tighter. How far does NUS see itself as a separate from the lives students lead and professors as educators of disciplines and content?

When asked about the role they play in NUS, some participants said, “As a prof, I teach just the content, and someone else will take care of the other aspects of students’ lives—the NUS Office of Student Affairs (OSA), NUS Health and Wellbeing (HWB), the NUS Office of Alumni Relations (ORA) etc.” Yet others said, “No, we need to teach students how to be whole persons—that means calling out bad behaviour, encouraging discussions about society without failing the advocacy test (being pro-PAP or pro-Opposition), talking about ‘taboo’ issues (the culture war has always been here…) etc., all of which may have nothing to do with grades.” What roles do we need to play? Is additional training and support what is needed, and if so, who will provide it?

How we educate

NUS has made many curricular and pedagogical changes to prepare students for the future—flipped classrooms, common curriculum, the S/U option2, internships, focus on skills etc. Given that cultivating a capacity for dialogue in our students—indeed, learning—requires human relationships and space, what trade-offs have we accepted?

-

- The flipped classroom gives students and lecturers more flexibility, but reduced contact time. This makes it harder to build rapport and connection, which are necessary for good teaching. What is needed in this new teaching/learning environment?

- Our aim is to teach students what they need in the future, the ability to do fact checking, exercise criticality and recognise manipulation through data etc. What else do we need to teach, and how do we ensure transferability of such skills into the workplace?

- We recognise that some things are best taught outside the formal curriculum. By emphasising outcomes in activities best conducted through student life programmes, have we inadvertently created new sources of stress and anxiety? Can we measure successes differently?

- We want students (and researchers/lecturers/tutors) to collaborate and work and learn in an interdisciplinary manner. What kind of environment do we need to create to support this? What new behaviours do we want to see, and what incentives are needed to encourage them?

- We have seen a rise in tribalistic behaviours across the world; have we inadvertently entrenched these? What can we do to help our students have the skill, willingness, and language to embrace diversity?

- Tutors understand the stresses the students are under, and try to reduce the more administrative aspects where possible—students pick up readings and notes from the Co-op, put students in reading groups, and solve their in-class social problems. In taking away these frictions, have stuents missed a chance to negotiate, compromise, and self-organise? Can we engender this in a more meaningful way?

Modelling?

Participants appreciated the opportunity to talk candidly without worrying about reprisals, to connect with colleagues they might not usually meet in their respective disciplinary contexts, to uncover serendipitous synergies, to find out what is going on outside their pond, and to feel less alone. As one said, “I’m not the only one who thinks that way.”

What was clear from the conversations was that people want to have platforms to talk about issues they are concerned about. This requires dedicated time and space to happen. It requires a willingness to listen and engage, and to embrace the differences. It requires regularity, so that the discourse “muscle” can be built up. It requires repetition so that trust can be engendered, mindsets can broaden, and opportunities for review and consideration can be worked in.

This may sound similar to what faculty said students need to dialogue and learn. Indeed, the University remains a place where students (and researchers/lecturers/tutors) explore, discover, make mistakes and find themselves. For the NUS community then, the skill of discourse, whether public or otherwise, remains germane.

The Futures Office will continue to engage Faculty through various platforms like the Senior Management Retreat, ad hoc workshops and through direct engagement. We would love to continue this conversation to not only make sense of, but also make something of the discourse surrounding the discourse.

Endnotes

- “When a meeting, or part thereof, is held under the Chatham House Rule, participants are free to use the information received, but neither the identity nor the affiliation of the speaker(s), nor that of any other participant, may be revealed.” Refer to this link for more details.

- The grade-free scheme at NUS is offered as an S/U (“Satisfactory/ Unsatisfactory”) option. Refer to this link for more details.

|

Katrina TAN is Senior Associate Director at NUS Futures Office. The team explores the futures of higher education in general, and the roles and impact of NUS specifically. They engage with stakeholders to look at issues and trends in the higher education space through different lenses, and to revisit assumptions and “grand truths”. Katrina can be reached at Katrina.tan@nus.edu.sg. |