by Flora Debora Floris

Petra Christian University (Surabaya, Indonesia)

Introduction

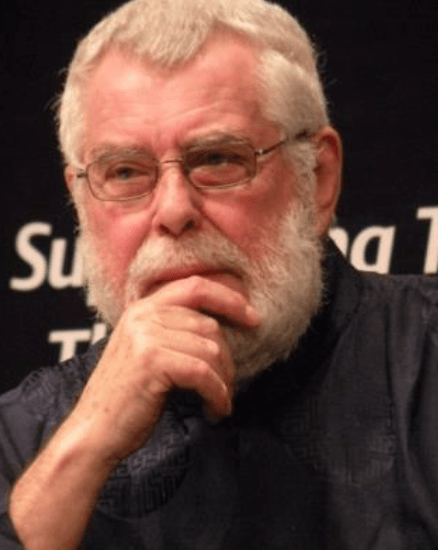

Prof. Alan Maley has been involved in English Language Teaching (ELT) for over 50 years. He worked for the British Council in Yugoslavia, Ghana, Italy, France, China and India. For 5 years he was Director of the Bell Educational Trust in Cambridge. He worked in universities in Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia as well as in his native country, UK. For 25 years Alan was Series Editor for the OUP Resource Books for Teachers series. He has published over 40 books and numerous articles.

Alan has been privileged to work with some of the ‘greats’, well-known people such as Michael Swan, Robert O’Neill, Ron Carter, Earl Stevick, and N.S. Prabhu. He has also derived great pleasure and happiness from working with all manner of teachers worldwide, ranging from primary teachers in Ghana, secondary school teachers in France, MA students in Thailand, and teachers in private language schools in a whole variety of contexts.

But apart from the people, Alan says, “I have also received great satisfaction from the way ideas and new approaches have evolved over the years, and the passion which drives that process. As part of this I have felt encouraged by the growth in self-esteem among us deriving from the way we have to a large extent established ourselves as a profession.”

Creativity

Alan has written and presented extensively on creativity in language classrooms because he believes that creativity is an essential component of effective teaching and learning process. “The creative spark is what ignites the fire of learning. Without it, we are left with dull, demotivating, routine teaching – the kind of instructional treadmill we see all too often in classrooms around the world,” he explains.

Having curricular and administrative constraints is probably one of the common reasons why classroom teachers are often reluctant to bring and develop creativity in their language classrooms. “But creativity can permeate everything we do,” says Alan. In his words, creativity does not have to be a major, epoch-making change. Creativity can simply mean “do the opposite,” as proposed by John Fanselow in his book Breaking Rules (1987). “These may be quite small things. If we usually allow students always to sit in the same places, we can ask them to sit in a different place in each lesson, and see what happens. We can vary the way we take the attendance register, the way we set homework, etc. There is an infinite variety of ways to be creative which does not require us throw out the whole curriculum; and this includes ways of adapting the material in the course book.”

What is more interesting is the fact that creativity shall be developed within constraints. In teaching creative writing, for example, the constraints may come in the form of word-limits (for example, a mini-saga is a story told in exactly 50 words) or in the formal constraints of a particular form of poetry (for example, the haiku, which traditionally, has to have 3 lines, of 5, 7 and 5 syllables). According to Alan, “these constraints also scaffold and support the learner, because they impose limits on the language needed.”

Alan firmly believes that creative writing activities are highly effective in developing the full range of language skills, especially vocabulary, and the sense of rhythmic patterning as well as improving students’ self-esteem, motivation, and self-discovery. He further asserts that creative writing can be taught for all students in all levels, including those who study for their master degree. “I put this to the test at Assumption University, Bangkok, where I set up a creative writing module on one of the MA modules I was running,” says Alan.

The Aesthetic Approach

In the past few years, still in the light of creativity in language classrooms, Alan has developed what he calls as the Aesthetic Approach. This is an approach which, in his opinion, “gives far more prominence to the art and the artistry of teaching” because what he is proposing is more than just “a narrow and rigid set of procedures to be applied in a mechanical way”. The Aesthetic Approach is more an attitude of mind, which favors certain kinds of materials and ways of doing, within a certain kind of atmosphere. It has three areas for implementation: The Matter, the Methods and the Manner.

The Matter, according to Alan, concerns the content. The Aesthetic Approach advocates a wider use of images from art, moving images, music and song, a wide range of nonreferential texts from literature and elsewhere, and student-made input. “This is the art,” he says.

The Method involves both art and artistry. In this case, Alan suggests teachers to “use more project work, ensemble work (for performance, etc.), more autonomous engagement by students, more multi-dimensional activities engaging all the senses, problem-solving and critical thinking, and playfulness through exposure to humour, games and creative writing.”

The last area is Manner, which needs all the artistry that can be mustered. This involves “the need to create a learning atmosphere encouraging ‘flow’ states, an attitude of openness to experiment and risk, offering choice, and developing a learning community bound together by mutual trust and support.”

When asked to give one or two examples on how to use the aesthetic approach in language classrooms, especially in Asian context, Alan unhesitatingly states, “Asian ELT classrooms could use a lot more texts written by Asian authors in English. The quantity and quality of writing in English in Asia is extraordinary. Yet very little of it is drawn on. Another area which could usefully be developed is story-telling, using local stories and the whole range of story types, ranging from jokes and anecdotes to wisdom stories and urban myths. Stories are such a powerful way of attracting the interest of students, and of developing language skills.”

Teacher training courses

For many people, enrolling in a teacher education or teacher training course is often seen as the first step of becoming ‘real’ teachers.

To this, Alan recommends strongly modifying the existing programmes to offer novice teachers more enormous help in two particular areas. “The first would be to include components to do with the content and skills needed for a creative approach, for example, training in using drama techniques, the use of the voice, story-telling techniques, using images, using music and song, etc. The other would be to develop sessions to help teachers become more skilful at improvisation and spontaneity.”

Alan further explains that classrooms are an arena of unpredictability, but he continues by stating that what pre-service teachers often receive is a set of toolkit of knowledge and skills supposed to work in most circumstances. In other words, novice teachers receive no training to meet the unexpected. “Usually, the problem is swept under the carpet by claiming this is something only experience can teach. But there are many ways we could help put teachers into a state of preparedness. That would be a real plus, not just to prepare teachers for the expected but to put them in a state of preparedness for the unexpected,” Alan asserts confidently.

This is actually applicable for service teacher trainings as well: “The best way to encourage service teachers to try out some of these things is to demonstrate that they work and that they are not so difficult to do. So, I would include hands-on sessions on drama, voice-work, storytelling, creative writing etc. on teacher courses.” Many years down the road from when he first started, Alan has witnessed how a cooperative and non-threatening training atmosphere would successfully transform teachers’ reluctance into enthusiasm and willingness to try using creative works in their classrooms.

ELT: The past, present and future

When Alan started his teaching career with the British Council in 1962, behaviourism was the psychological theory of choice while audio-lingualism and the memetics movement were riding high and the Structural-Situational Approach was favored. In the 1970’s and 80’s, Alan says he saw and experienced how the Functional-Notional Approach was transforming itself into the Communicative Approach, which has since morphed into Task-Based Learning.

In those days, Alan also had the privilege “to have a ringside seat as the so-called designer methods broke cover: The Silent Way, Suggestopoedia, Community Language Learning, Psycho-drama, Total Physical Response, and so on.” Recently, Alan has seen the rise of the Dogme Approach, the development of Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) and the expansive introduction of technology as a necessary component of ELT.

Apart from this, Alan has observed what he calls as ‘control culture’ in education, which is the result of “a results-oriented, measurement-driven system of education, obsessed by

‘objectives’ and driven by examinations, tests and assessment.” He further adds with conviction, “One of the results is that materials are now virtual clones of each other, so the creativity of materials writers is being stifled by risk-aversive publishers. Another is that teachers are given less and less freedom to exercise autonomy and creativity in what they do, and stifled by the weight of extra administrative duties and various forms of bean-counting.”

Alan also has paid attention to the value of research. Alan observes that there has been a growing number of teachers furthering their studies to earn an MA or PhD. However, he remarks that “this flies in the face of the evidence that there is no necessary connection between research and teaching, that there are few instances where research is of any practical use, and even when it is, it is routinely ignored by administrators, that doing research for a PhD rarely if ever improves the teaching quality of the candidate, and that most teachers are not well-equipped to carry it out anyway.”

In the future, Alan would like to see more teacher development programmes focusing on creativity and that teachers be given more opportunities to exercise their initiative and creativity. Alan also wishes that teachers would eventually move back from an excessive addiction to testing and conformity.

Current projects

In 2003, Alan set up The Asian Teacher-Writer Group, which operates with the belief that Non Native Speaker Teachers (NNSTs) in the Asia region are capable and uniquely wellplaced to write literary materials for use by their own and other students in the Asia region. This is based on the conception that these teachers share their students’ backgrounds and contexts and that they have an intuitive understanding of what will be culturally and topically relevant and attractive for both teachers and students in Asia.

The group is independent of any institutional support and is entirely voluntary. Each year, a volunteer takes on the responsibility for finding local sponsorship and organising a creative writing workshop in a different venue in Asia. The group has also published some original stories and poems and resource books for use with students in the Asia region. Some of the materials and resources developed by the group are available at http://flexiblelearning.auckland.ac.nz/cw/.

Alan is passionate about sharing The Asian Teacher-Writer Group’s substantial achievements to others: “The group has been restricted to Asian countries purely for reasons of practicality. Imagine trying to run something like this on a global scale with zero financial resources and no administrative support. But there is no reason why others, elsewhere in the world, should not use the same model to develop their own groups. This is boot-strapping at its best.”

In 2013, at The 48th Annual International IATEFL Conference, Alan introduced The C Group (Creativity for Change in Language Education), a group of ELT professionals with a shared belief in the value of greater creativity. The group exists to give support and encouragement to teachers who have creative ideas of their own.

He elaborates saying, “Our C Group is not going to tell people what they should do to solve their problems, or implement creative change. It is not there to act like a wet nurse for helpless teachers. There is too much ‘learned helplessness’ around already. What we want to do is to foster independent initiatives coming from the membership, not to impose solutions on them. ‘Therefore, ask not for whom the bell tolls – it tolls for thee.’”

The C Group’s manifesto states as clearly as possible what the group is about (refer to http://thecreativitygroup.weebly.com/). “This group is open to membership to anyone who feels comfortable to subscribe to these points,” Alan adds.

… and beyond

Alan is an avid reader; and he reads promiscuously – newspapers, novels, current affairs books, popular science and sociology, biography, travel writing, crime writing, horror writing – certainly not just in applied linguistics, methodology and the like. Teachers, in his opinion, should read about things that are over the “ghetto wall of ELT” because this will open their minds.

Alan also writes a lot, especially poetry, as he finds that poetry offers him new insights into the world and new ways of looking at it and making sense of it. He has also started to write memoirs about his childhood and professional career.

In his spare time, Alan loves to listen to music (mainly western classical, but also jazz, Indian classical & some folk traditions) for all its redeeming qualities, and he likes preparing and having good food and drink, especially wine. He also enjoys walking as he considers it a psychological as well as a physical activity, and a machine for thinking. Interestingly, Alan further says, “And I am getting quite good at doing nothing. Idleness has great virtue.”

To end our interview, Alan harkened back to the topic of creativity, stating that he would recommend teachers to check a list of the following readings and video, and yes, after that, “Just get on with it.”

Recommended readings & video

Maley, A. (2012). Creative writing for students and teachers. Humanising Language

Teaching, 14(3). Retrieved from http://www.hltmag.co.uk/jun12/mart01.htm

Maley, A. (2009). Towards an aesthetics of ELT. Part 1. Folio: Journal of MATSDA, 13(2).

Maley, A. (2010). Towards an aesthetics of ELT. Part 2. Folio: Journal of MATSDA, 14(1). Underhill, A., & Maley, A. (2012). Expect the unexpected. English Teaching Professional, 82. 82.

Underhill, A., & Maley, A. (2013) From preparation to preparedness (Video File). Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jIBhUVhmYOo

References

Asian Teacher-Writer Group. (2012). Creative writing: Asian English language teachers’ creative writing project. Retrieved from http://flexiblelearning.auckland.ac.nz/cw/

Fanselow, J.F. (1987). Breaking rules: Generating and exploring alternative in language teaching. New York: Longman.

The C Group. (2013). Creativity for change in language education. Retrieved from http://thecreativitygroup.weebly.com/

Acknowledgments

I would like to extend my sincere thanks to my MA lecturer, Prof. Alan Maley, for his valuable participation in this interview. He has been my guru, and a source of inspiration; and I hope that ELTWO readers will enjoy reading this interview piece and be intrigued by his insightful ideas.

About the author

Flora Debora Floris is a lecturer at the English Department of Petra Christian University, where she teaches English Education Business subjects. She has published and presented internationally on teachers’ professional development, technology in language teaching, and English as an International Language. Flora also serves as a member of review or editorial boards of some national and international journals.