by John Spiri

Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (Tokyo, Japan)

Abstract

This paper reviews class management strategies and suggests integrating teacher cognition principles in the process of articulating classroom rules and policies. Teacher cognition involves an exploration of beliefs, experiences, and ideals that may influence policy making that aims to achieve desired outcomes. Surprisingly, teacher cognition research shows that teachers are not always aware of the reasons why they do what they do in the classroom. To deal with class disturbances, a number of approaches are discussed and summarized. Finally, an example of employing teacher cognition when considering three class management policies, rotating students’ seats, dealing with sleepers, and dealing with chatterers is provided.

Introduction

My ex-colleague at a university in Japan had an effective way to handle students who spoke Japanese in their English classes. He would pick up their books, place them outside the door and tell the offending student to go home. He reported that one of the first students to be kicked out this way briefly protested and even cried, but he simply told her, “See you next week.” His students stopped speaking Japanese in class.

Draconian rules do tend to get results. But such strictness raises a number of questions. Is use of L1 really that offensive? Did the students have a voice in this policy? What effect did the threat of expulsion have on students overall feelings about the class and attitudes towards English? Does the teacher have a right to evict a student in this (or any) circumstance? Might there be a better way to achieve results?

Classroom management poses special challenges because a teacher may lash out at an offensive student in an emotion-charged instant, continuing a pattern of behavior that may not be the most effective, and may or may not have been carefully examined. Moreover, classroom disturbances and “problem” students are particularly difficult to categorize and thus making it difficult to decide an appropriate reaction/punishment beforehand. Ideally, teachers make classroom rules and policies and take disciplinary action only after careful consideration of their beliefs and attitudes about learners, education, and the classroom situation.

Teacher cognition (TC) involves and investigates the practice of teacher self-reflection. Exploring and understanding TC in the context of classroom management challenges might be even more valuable than the context of planning lessons and activities. Activities are typically thought out well in advance while teacher expressions of discipline or managing disruptive situations within the classroom interaction must usually be made instantaneously.

Managing classrooms

The cases and descriptions provided in this paper come from English classes at universities in Japan. Some of the perceived disturbances may be connected to culture. For example, Canadian Robert Norris (2004) explains, “Sleeping in class, tardiness, and bad attendance may be connected to a different view…of the university experience, wherein peer pressures in club activities and part-time jobs take precedence over attending class. Handing in the same homework and chattering in Japanese may be connected to group-mindedness and the Confucian idea of the importance of copying a master’s work to improve oneself.” It is beyond the scope of this paper to explore the degree to which Japanese academic society accepts behaviors such as chattering and sleeping in class, but rather explore ways that teachers in Japan deal with them.

Of course, thoughtful preparation and skillful delivery on the teacher’s part can create an atmosphere where behavior problems tend to not occur. With surprisingly antagonistic wording, Amber Wilson (n.d.) discusses class management in “Engagement—A Preemptive Strike Against Classroom Misbehavior.” She writes,”A classroom teacher has many weapons in her arsenal to fight classroom disruptions and misbehavior.” One may infer from this title and opening line that the teacher views her interactions as battles, and at least some of the students as enemies to overcome.

In a gentler fashion, William Glasser (1998) has pointed out that students are less likely to misbehave when the curriculum has meaning for them. He encourages teachers to reject the “old boss-managed system” and understand students may not be complying “because they do not find it (the assignment or lessons, for example) need-satisfying” (p. 6). While public school children are forced to attend school, university and college students are not. Still, university students may be required to take an EFL class that doesn’t interest them or satisfy their needs, so the point remains relevant for tertiary students as well.

Richards, Gallo & Renandya (2001) explain the results of their in-depth survey of teachers’ beliefs about language teaching and learning: “There were many comments about class atmosphere and the conditions necessary for language learning. These include the need to create a fun, motivating, non-threatening and secure learning environment and to create a language rich environment in which learners could be constantly exposed to and use the language… and finally that class atmosphere is as important as content and pedagogy” (p. 4). A positive class atmosphere will surely defuse many kinds of disruptions. But for any number of reasons disruptions sometimes occur despite a teacher’s best efforts.

At the crucial moment of disturbance the teacher has many ways to respond. When there is excessive chatter a teacher may yell, throw chalk or an eraser at the offender, approach and stand next to the talker, stop talking and silently stare, or ignore the situation and keep on talking. Wagaman (2010) recommends, “When a student acts up in class or breaks a rule, identify exactly the wrong-doing. Addressing specific behavior will reinforce the rule for the individual student, and the entire class.” An extreme disturbance may be easier to deal with because it demands an immediate response while chronic low-level disturbances may be more difficult. Teachers who too quickly try to stop a conversation between two students run the risk of alienation, especially if the conversation was lesson related. Most agree that it is unreasonable for a teacher to expect absolute silence outside of discussion related to activities. Kizlik (2010) notes, “Most inappropriate behavior in classrooms is not seriously disruptive and can be managed by relatively simple procedures that prevent escalation.”

Regardless of how experienced a teacher is, new classes with new students, perhaps at a new school, often produce novel problems. Rather than just considering courses of action for a particular case or making general classroom rules, a teacher should also consider his or her overall values and philosophy of education. Forcing students to comply via disciplinary action, even in the form of evicting a student from class, may be required in some cases, especially extreme and continual disturbances by a student. While teachers will ideally defuse potentially disruptive situations before they become problems, the main focus of this article is on situations that have escalated to the point of needing attention, for whatever reasons.

There is no shortage of advice for teachers on how to manage the behavior of students in class. Key points for teachers to remember in regard to a disruptive student, one who is incessantly talking or disturbing others in some other way, are covered for instance by Churchward (2009). He recommends as follows: “Get the attention of all students – Trying to talk over disruptive students or ignoring them often legitimizes the problem. Wait for the talker(s) to stop. This may include long silences and stares that normally make people, and especially students, uncomfortable. Use body proximity if necessary. A poised, silent reaction is preferable to anger.”

The same author also suggests using “non-verbal cuing,” explaining, “A standard item in the classroom of the 1950’s was the clerk’s bell. With one tap he had everyone’s attention. Teachers have shown a lot of ingenuity over the years in making use of non-verbal cues in the classroom. Some flip light switches. Others keep clickers in their pockets.”

Once the student’s attention is gotten, Kizlik (2010) suggests, “Redirecting the student to appropriate behavior by stating what the student should be doing; citing the applicable procedure or rule.

Example: ‘Please, look at the overhead projector and read the first line with me, I need to see everyone’s eyes looking here.’”

Most teachers would agree on the need to follow through on implementing rules. If class policy states that disruptive students will be marked absent after given a warning, the teacher should not keep issuing warnings to a problematic student. Rather, after the first warning, the student should be marked absent. For teachers, maintaining consistency with rules when dealing with various students is crucial.

The rules and policies a teacher formulates, however, will vary from teacher to teacher and situation to situation. Class policies should be articulated with a clear understanding of the reasons and values that make them desirable and the best course of action. Thus, before formulating a policy, a teacher should reflect on his or her beliefs, thoughts and experiences related to classroom management. Teacher cognition provides teachers with the opportunity for reflection on values and reasons for actions that take place in the classroom, which is particularly helpful for formulation of classroom policies.

Teacher cognition

Teacher cognition (TC) involves examining what teachers think, know and believe (Borg, 2009, p. 1). In part, TC is grounded on the notion that a teacher’s mental activity influences his or her instructional choices. Surprisingly, TC research has demonstrated that teachers do not always have an awareness of or a rationale for the activities they utilize in the classroom. Borg explains that teacher cognitions are “not always reflected in what teachers do in the classroom” (p. 3). Awareness of thoughts about a classroom practice, which could include biases, memories, ideals, etc., may or may not influence choices. For example, a teacher who questions her reason for assigning a grammar activity may conclude that the only reason she chose that activity is because she did similar activities as a student. Awareness of this fact may lead the teacher to critically examine the effectiveness of such activities based on a number of other criteria.

Teacher cognition is generally conducted by researchers and teacher trainers in order to learn more about teachers’ classroom related decision making processes, most often regarding lesson planning and choice of activities (Borg, 2009, p. 98). Surprisingly, however, TC has had little to say about class discipline. Borg (2003) notes that, “problem behaviour rarely seems to be an issue in the classrooms described in the literature on language teacher cognition” (p. 94). Borg goes on to conjecture that the reason might be because TC studies are often conducted in language classrooms that are atypical, i.e. small class of adult learners. Thus, classroom management is less a challenge for language teachers than for public school teachers.

Richards (1996) does connect TC to classroom management describing the cognitive influence in terms of a teacher maxim that calls for order and discipline throughout the lesson. While university faculty members do not generally need to deal with the degree of misbehavior that occurs in public schools, they are not without class management challenges. In Japan, for example, classes often include 30 or more students who might be unmotivated, disinterested, and/or disruptive. Hence, there is value in self-exploration so individual teachers can ascertain their own values before establishing class policies. Below are the descriptions of three university teachers in Japan and their TC regarding issues of classroom management, including student seating, student sleeping and student chattering.

Teacher A

Teacher A: As a 49-year-old female teacher from New Zealand with 20 years of teaching experience, 10 in ELT, she exclusively described her experiences at a university where students had an unusually low English level and where behavior problems, sometimes severe, were not uncommon in classes of approximately 33 students. She can be described as genki (highly energetic) and positive.

Student seating

Teacher A insists from the start of each semester that all students occupy the front 4-5 rows (25-30 students in classes), 2-3 students per long table. Within that arrangement, she permits students to sit where they want. She reported that some discipline was needed to make this work. For example, she would arrive in the classroom early, and quickly move (jam up) the back 4 rows so that students obviously could not sit there. Then as students arrived, she would smile, greet and say, “please sit here” gesturing to the front 4 rows.

Cognition: According to Teacher A, the importance of having students sit toward the front was learned through experience. Also, she made such an arrangement because could not always hear Japanese students’ answers if they sat at the back. It was up to her to invite them up front and help them feel part of the group and the learning, etc. However, she reported that it was good to give students some autonomy at the beginning of a class, letting them choose where they would sit. Then under the guise of language practice, she would move them round for activities. She wanted to avoid ‘battling’ them every week.

Evaluation: According to Teacher A, this worked well. Her “persistence with a smile” seemed to win students over. This is most effective when instituted from the start of the semester. It is up to teachers as the role models to set the boundaries. Humor also helps the effectiveness of this request.

Sleeping in class

Cognition: Sleeping in the classroom is not acceptable in any country in the world. Teacher A stated this rule right from the first class. It was also in her university’s “Code of Conduct,” so students who signed it agreed to not sleep in class. If a student was nodding off, seeming genuinely tired (as opposed to bored/lazy), she might have checked quietly to determine if they were feeling sick, etc., and she would then gently suggest that they stand up and drink water. If that did not work, she might say, “OK, for today, it’s better you go home and rest, because you’ll be marked ‘absent’ if you continue to sleep anyway.” According to Teacher A, students would generally wake up and participate. The key here seems to be to stand firm that sleeping is never allowed.

Common sense says that if students sleep, they do not learn. It is part of our role as educators to guide students to develop social skills and life skills, and not just language learning skills. Students need to learn self-management skills and awareness of what might cause them to be tired (e.g. part-time jobs, staying up too late playing computer games, etc.) and to make necessary adjustments to their lifestyles so they can stay awake in class and make the most of their learning opportunities.

Evaluation: Setting ground rules from the very start of the semester makes this policy effective; Teacher A no longer has students who sleep in class. Still, it seems important to be both gentle and firm. A teacher should find out if there is a genuine reason why a student is sleepy and then proceed from there.

Chattering in class

Cognition: According to Teacher A, this was a huge problem, especially since she had hearing problems. She tried a number of tactics to curb class chatter:

- She asked students, in “poor” Japanese, to please stop talking. The key was she always addressed students by name.

- If they chattered, she wrote their name on the board, and if a name went up three times, that student got marked absent. She reported that such an approach was a fairly effective deterrent.

- If the class was doing any teamwork for points, students who chattered lost points.

- She would ask chattering students to stand up for a while, at least until they stopped chatting. Students would be asked to stand up again if the chattering resumed.

Once with two extremely disruptive chatterers, she got her Japanese coordinator to mediate a meeting. At the meeting she and the coordinator checked whether the students wanted to change classes. The “Code of Conduct,” the university-wide policy document, was shown to them again. Both times, she said, this resulted in sufficient improvements. It was, however, a last resort. Her experience has shown what short attention spans and lack of self-discipline many students have, even the most pleasant kids. In her opinion, they need teachers to stop them from chattering, and somehow make them accountable to each other.

Evaluation: After a few reminders, most students are able to self-manage and focus on the classroom task and not chatter so much. A few remain a constant disturbance, so tactics such as standing near the chatterers while giving instructions or conducting class feedback is useful. Changing seating by making new pairs is the most effective and positive measure, as then the chattering student tends to focus on the task due to unfamiliarity with their new partner.

Teacher B

Teacher B: As a 40-year-old male teacher from the United States with 12 years of teaching experience, he mostly described his experiences at a university with students who were above average in terms of English ability (in the Japan context) and where behavior problems were uncommon in class of typically 8-12 students (with a maximum of 25). He also commented on his memory of teaching in another context where behavior problems were fairly common. In terms of personality, Teacher B can be described as unusually calm and low key.

Student seating

Cognition: Teacher B has not felt the need to formulate a seating policy and allows students to sit wherever they like. However, he often divides students into teams for discussion activities and uses this opportunity to separate particularly talkative groups. And on days when he doesn’t have plans to divide students into groups, he does so if the students seem overly talkative.

Sleeping in class

Cognition: In general, he is sympathetic about sleeping in class and does not view it in very negative terms observing that life can be too demanding for students with part-time jobs, clubs and other social activities, and studying. Still, he makes an effort to curb sleeping in class because a sleeping student is obviously not learning or contributing. While he might wake up a male student with a gentle tap on the shoulder, he would never touch a female student. In either case he might brainstorm with the sleeper to find ways for them to stay awake. Since Teacher B strives to promote a feeling of community among students, most commonly when there is a problem he quietly suggests that a neighbor wake any sleeper. He might also mention in class something about openly acknowledging sleepiness and its causes, tuning into students’ levels of wakefulness and making adjustments (throwing in a funny story, changing seats, etc.)

It was difficult for Teacher B to pinpoint influences on his values. He reported that he had started teaching (in Korea) on “a whim,” and that after earning proper qualifications, he came to really enjoy the job. He noted that the world was complicated, and he could not always feel that he had lived his highest ideals or always avoided trouble, but he said that the classroom was a limited environment which had given him more of an opportunity to be the person who he wanted to be. The aim of living his highest ideals, being calm, reasonable, and not reacting angrily in the classroom, was what drove him, he said.

Evaluation: He feels his approach to working with sleeping students is effective though he acknowledges that he rarely encounters any particularly challenging individuals or groups of students.

Chattering in class

Cognition: Teacher B viewed this as more of a problem than sleeping in his classes. One reason for that, he said, went back to his view of the classroom as a community. He reported that when facing the problem of chattering, he would simply say to the students, “I need your attention,” and this generally worked sufficiently. However, he recalled a previous teaching context with students who walked into class not only late but noisily. He would speak sternly to them, admonishing, “Very few things make me angry, but your talking when I’m talking to the class does make me angry.” Even in that context, tension had persisted with one male student, but by the end of the term, the student privately told Teacher B, “I like you, your toughness.”

When disciplinary action, like a stern voice, is used very sparingly, it is much more effective. Teacher B recalled this point being made in a blog post with regard to swearing: Whenever an individual would use socially unacceptable words such as “the f-bomb,” the effect was substantive. Teacher B said that this same effect could be applied within teacher behaviors. He also reemphasized that the main influence on his own approach was the concept of the community being a classroom. He said that while he did not write any rules on the syllabus or course description, early in the semester he made a point to note, “This is our team” or to remind students that they were among friends (classmates).

Evaluation: Teacher B acknowledges that very few behavior problems arise in his classes. Still, he views classroom management as a “favorite” aspect of teaching and he said that he makes a consistent effort to facilitate “interesting, dynamic, exciting, fun and funny group experiences.” Finally, he indicated that discussing classroom management with others made him feel more prepared should a problem arise.

Teacher self-reflection

The notion of teacher cognition need not be limited to researchers and teacher trainers collecting data about practicing teachers or those in teacher training programs who might be interpreting those results. The process of reflection on and consideration of beliefs, knowledge and thoughts regarding the classroom can be done by teachers themselves for their own purposes. Nuckles (2000 qtd. in Brown 2000) notes that “Teachers need to examine their belief structure regarding education and engage in an ongoing process of diagnosis, with self and with learners, including observation, questioning, obtaining evaluative feedback, and critical reflection” (p. 6). This process of cultivating self-awareness and determining motives for classroom policies is particularly valuable for those teachers seeking to defuse or avoid volatile or merely disruptive situations. Since challenges may vary from student to student and situation to situation, the emphasis on process, while continually evaluating and reevaluating one’s policies and approaches and the rationale for those seems particularly important.

One of the main advantages of self-reflection is that it generates choices. Self-reflection can lead teachers away from patterned responses and to a selection of a number of responses in any given classroom situation. Pratt (2002) says, “Proficient student-centered teachers are able to use a variety of styles so that their ultimate style is integrated” (p. 6).

Some situations demand teachers to be more skilled at handling disruptive students than others. One medium-sized university in Tokyo has a high rate of all-male part-time teachers and a high rate of attrition, at least in part because students are extremely unmotivated, immature and disruptive in the classrooms. The author of this paper and the other part-timer teachers who were surveyed for this study had only taught there for one semester, while the full-time teacher was in her second year. Predictably, the full-time teacher had developed many more effective strategies for dealing with problem students than the part-timers had. The part-timers, however, were able to reap benefits by considering the full-timer’s advice on approaches to management and by immediately making adjustments. As an example of this, the part-timers began referring to offending students by name and by keeping the back row in the classrooms empty.

Teacher C (this paper’s author)

Background: The classroom management issues described below are from the author’s experience at a science university in Japan. Education majors in the author’s classes demonstrate occasional but not excessive behavior problems. Classes for those majoring in education consist of 30-36 students, most of whom are generally motivated and serious about improving their English skills. While the university employs no testing or placement program, it can be noted that these students are especially proficient at reading and listening yet reluctant to speak. In contrast, non-education majors at this same university show extremely low motivation and extremely low skills and poor attitudes. It is fair to say they have given up on English and are only attending the class through compulsion. For example, because of the fact that so many of these students had failed in previous years, the program director instructed all faculty members to pass every student, with the only exception being students who were absent for more than half of the course classes. What follows is a brief description of my cognitions regarding each particular issue.

Student seating

Cognition: Students who sit with the same partner week after week are susceptible to falling into bad classroom habits due to increased familiarity and friendship. These students often chat excessively in their native language of Japanese, and this is not conducive to optimal language learning. Also, it is worthwhile for students to leave their “zone of comfort,” which might normally include bonding with just one or two close friends. Students benefit from working with a number of partners who provide varied ideas and have varied levels of English proficiency. Thus, when a teacher takes the initiative to have students change partners, the student is provided new opportunities for growth. In fact, individual students often want to change partners but are shy to initiate the change themselves. However, teacher coercion and confrontation are to be avoided. What approach might then work best?

Seat Rotation System: On the back of my class syllabus there is a space for students to write a different partner’s name each week. In one particular class, a quick calculation led me to remind the girls–8 out of 33 in the class–that after the 7th class they were expected to sit next to new partners, who would have to be male. When the week finally came, and they had once again congregated in their usual “girl section,” I tried to usher them out into rows with males. This met with painfully long pauses of hesitation. Several girls stood, looked around, but were frozen for what seemed like several minutes. A couple others stayed put in the back of the class. Only after several minutes of animated encouragement on my part did the females finally move to partner with males.

When they finally had paired with new partners, they interacted productively in English and seemed invigorated with the new male partners. The following week, however, I found even more hesitation from the girls to find new partners. Only another herculean effort finally inspired them to scatter throughout the classroom and to sit next to and interact with their male peers. They eventually did this successfully. When in another week (Week Ten of the 15 week course) I encountered the same reluctance, I faced the decision whether to either force again them to pair up with another or to drop the issue. I had tried to implement my preference with gentle and sometimes light-hearted persuasion. In the end though I acquiesced to the preferences of the female students and allowed them to stay with familiar partners. This decision came about, in part, due to my conviction that coercion should be avoided.

Evaluation: By reflecting on this situation and how I might better articulate class policy and a management approach in the future, I felt more prepared to react in accordance with my values. A teacher who believed more strongly in the teacher’s managerial role might have taken a further step to force the females to find new partners; another teacher who was more skillful at communication might have convinced them to move in that direction. Whatever the case, the value of TC is that it provides a teacher with the opportunity to reflect on values, make class policies agreeing with those values, and observe the effectiveness of such policies as expressed in classroom management aproaches. In my particular case with regard to the chattering, no serious problems emerged so an exception seemed acceptable.

Sleeping in class

Cognition: Sleeping in class is generally accepted by teachers in Japan. It is not uncommon to see Japanese students sleeping towards the back of a classroom while a Japanese professor gives a lecture. A certain amount of sleeping also seems to be tolerated at professional presentations and even at faculty meetings. Thus, many students expect to be allowed to sleep. However, students who sleep do not know what to do when the class moves on to an activity, which leads them to bother classmates with questions when they wake up. In addition, if one student sleeps, others are more likely to sleep or stop listening, so class atmosphere is compromised. My own delivery as a teacher is compromised when one or more students are not paying attention; a feeling of meaninglessness creeps into my mind, which bothers me, and I become distracted by my desire to wake the offending students. From my view, a student being present requires the person to be conscious, so a sleeping student is, in a sense, absent. Even as a matter of common courtesy, I feel that it is rude for students to be sleeping when I or the student’s classmates are talking. Ideally though, to gain compliance, coercion and confrontation should be avoided.

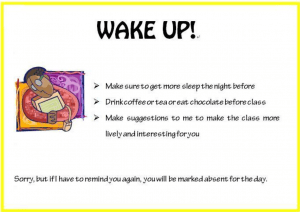

Card System: After a certain amount of patience with a student who may merely be resting his eyes or even listening with eyes closed, and after having used techniques such as moving to stand close to the sleeper, I wake the student and hand him or her a “yellow card” (see Figure 1). The yellow card provides stimulus for the student to stay awake. On it is written a list of suggested behaviors for the student: drink caffeine or eat chocolate before or during class, get more sleep at night, or make suggestions for the teacher to make the class more interesting. The last choice is meant to pass responsibility to the teacher to make the class better as it requests that the student discuss class content with the teacher rather than sleep. A final line on the card warns that a second card, the red card, will be given for a repeat offense and the sleeping student will be marked absent. My approach is to usually ask the guilty student and one or two nearby students to read the card silently. That and the threat of receiving the red card with an automatic mark of absence are usually enough to dissuade the student from persisting on sleeping. Also, I will generally confer with the student who persists in sleeping by asking how many hours he had slept (it is usually a “he”) and providing advice, encouragement and a reminder that the red card will mean absence. Only very rarely do I have to resort to handing out the second card and marking the student absent. Compared with enforcing seat rotations, in this case I will indeed rely on coercion if need be, but only after efforts to encourage and even discuss the issue. I try to give a lot of leeway before getting to the point of compulsion.

Evaluation: One advantage of this system is that it allows me or any other the teacher to target the sleeper, and perhaps those close enough to read the card, rather than disturb the whole class and possibly embarrass the offender with a reprimand in front of everyone. Having the suggestions and consequences in writing is also helpful because it gives the card reader ample time to comprehend and reflect on the situation. Thus, this system has effectively curbed sleeping in class with minimal disruption and minimal confrontation.

Chattering in class

Cognition: Chattering in class indicates that the chatterers are not listening, learning or participating. In addition to a possible problem with the attitude of the offender, the chatter also might be disturbing classmates. In part due to the influence of my study of Buddhism, I have great admiration for individuals who can hold their tongue and listen calmly. As a teacher, I also feel a responsibility to add to student’s listening experience by speaking in English in class. Of course, the potential for absorption and retention of a second language is higher when the individual student is a keen listener. Like sleeping in class though, chattering can be contagious as groups of students may join the conversation or start their own, thinking it is permissible. Thus, chattering is unfair to those wanting to pay attention and generally rude. However, a classroom should not be like a prison, and sometimes students may have something important to say or a light-hearted comment in L1 to make to a classmate. Some chatterers have unobtrusive timing and can briefly chat without missing important classroom interactions and/or without disrupting classmates. A certain amount of tolerance is preferable. Like my belief regarding other class management issues, coercion and confrontation are to be avoided.

Modified Card System: Initially chatterers are asked to quiet down. Another technique I have used is moving to stand right next to the chatterers even while still giving an explanation to the entire class. This usually prompts an end to a conversation. However, some students, either due to past habits or attitudes toward a particular class, persist in chattering. At some point I turn to the card system described earlier, handing the chatterers a yellow card first, which describes the problems with chattering and the consequence should they continue: absence. The red card is reserved for extreme cases (see Figure 2 below).

This yellow and red card system, intentionally light-hearted since it is borrowed from soccer with a design that incorporates amusing images, is unobtrusive as my viewpoint can be communicated in silence. It has great versatility, too, as cards can be created for other classroom management issues such as students attending without textbooks or other essential materials.

Evaluation: Like the above yellow and red carding of students who sleep, the card system has been an effective deterrent to the excessive chatter. It is also worth noting that this approach, developed while I was teaching in university English programs with relatively skilled and motivated students, were effective but were not as employable in the same form at a university with unmotivated and disruptive students. This demonstrates that there is a need for a cognitive process of discerning beliefs and making observations within specific situations and even for specific types of students.

Conclusion

Teachers can agree on the need to limit or eliminate disruptive or even unproductive actions by students. In the opening example the teacher took an extreme disciplinarian role by ejecting a student from class merely for speaking L1, an action which could even be viewed as tyrannical. This approach, however, did achieve compliance. Ideally, the teacher would have been aware of an array of other disciplinary actions, and he might have chosen the most appropriate action only after fully considering the influences of his values, beliefs, experiences and observations. In the end, teacher cognition is about self-awareness, surely a beneficial aim for all teachers.

Figure 1: A “yellow card” for students who persist in sleeping

Figure 2: A “red card” for yellow-carded students who continue to disrupt by chattering

References

Borg, S. (2009). Introducing language teacher cognition. Retrieved Sept 9, 2010, from http://www.education.leeds.ac.uk/research/files/145.pdf

Brown, B. (2003). Teaching style vs. learning style. Retrieved Sept. 14, 2010, from http://www.scribd.com/doc/6706642/LearngStyleVSTeachgStyle

Churchward, B. (2009). Discipline by design. In 11 Techniques for Better Classroom Discipline. Retrieved Sept 7, 2010, from http://www.honorlevel.com/x47.xml

Glasser, W. (1998). The quality school teacher. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

Kizlik, R. (2010). Education information for new and future teachers. InClassroom Management, Management of Student Conduct, Effective Praise Guidelines, and a

Few Things to Know About ESOL Thrown in for Good Measure. Retrieved September 14, 2010, from http://www.adprima.com/managing.htm

McCamley, M. (n.d.). One-stop English. In Classroom Management: Classroom Discipline. Retrieved September 7, 2010, from http://www.onestopenglish.com/section.asp?catid=59438&docid=146446 Norris, R. (2004). Some thoughts on classroom management problems faced by foreign teachers at Japanese universities. In Bulletin of Fukuoka International University, No. 12. Retrieved February 1, 2011 from http://www2.gol.com/users/norris/articles/classman2.html

Pratt, D. (2002). Good Teaching: One Size Fits All? Retrieved Sept 14, 2010 from http://www.fsu.edu/~elps/ae/download/ade5080/Pratt.pdf

Richards, J., Gallo, P. & Renandya, W. (2001). Exploring teachers’ beliefs and the processes of change. PAC Journal, 1(1), 41-64.

Richards, J. (1996). Teachers’ maxims in language teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 30(2), 281−96.

Wagaman, J. (2010). New teacher support. In Classroom Management Strategies for Teachers. Retrieved September 7, 2010, from http://www.suite101.com/content/ classroom-management- strategies-for-teachers-a205521

Wilson, A. (n.d.). ESL Teachers Board. In Engagement—A Preemptive Strike Against Classroom Misbehavior. Retrieved September 7, 2010,from http://www.eslteachersboard.com/cgi-bin/articles/index.pl?page=2;read=3596

About the Author

John Spiri has taught English for 14 years at universities in Japan, the last five at Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology. His research interests include CALL (computer assisted language learning), autonomy in education, and global issues in language education.