Selected Papers from the 6th CELC Symposium for English Language Teachers

Editorial Committee: Mark Brooke, Shenfa Zhu, Anuradha Ramanujan, Tetyana Smotrova, Sylvia Sim

First published: November 2022

Click to view a full listing of the symposium abstracts: ABSTRACTS

Click to view the PDF version: 6th CELC Symposium Proceedings

Foreword

Keynote addresses

Digital Tools for Promoting Social Reading

Tamara TATE & Mark WARSCHAUER

Future-looking principle-based curriculum innovations

Julia CHEN

Featured address

Decolonizing Language Beliefs and Ideologies in ELT

Ruanni TUPAS

Full length articles

Turkish EFL Teachers’ Perceptions About Online Teaching During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Burcu GÜL

No Grades Please! We are Learning

Sylvia SIM and Patrick GALLO

Short articles

Transforming the Pedagogical Landscape of English Teaching in Japan through Practical Support

Tony CRIPPS

Discipline Based Mini Lectures for English Enhancement (MiLEE)

Marc LEBANE

FOREWORD

The Centre for English Language Communication (CELC) held its sixth Symposium online, from 30-31 May 2022. Symposium 2022 gathered 144 researchers and educators from 14 countries in the pursuit of scholarly dialogue on the theme TEACHING ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND COMMUNICATION IN A CHANGING LANDSCAPE: INNOVATIONS AND POSSIBILITIES.

This year’s theme built upon many of our recent experiences and conversations in response to some unprecedented massive changes and challenges acerbated by the pandemic. If there is one word that we could use to describe the past two plus years, “disruption” is probably one of the most frequently used words. It seems timely that we take stock of our teaching, learning, and research as suggested by the theme of this symposium.

To me, the fundamentals are the same but the approach in which we achieve the objective may now be different. Besides re-examining and reflecting on what we have done, we re-imagine teaching, learning, and doing research in a new educational landscape. Our students are going into a workplace that is unlike before, a workplace that perhaps not many of us are familiar with. They need to be nimble, adaptable, and resilient. They must make sense of and integrate knowledge in different contexts. All these soft skills may call for a different way of thinking about teaching and learning, and communication.

CELC Symposium 2022 provided a platform for English Language and Communication practitioners and researchers to share and discuss:

- Challenges relating to teaching under the new norms such as teaching in the digital space, engaging and assessing learners with advanced interactive technological tools, and managing increased student agency.

- Innovations that have helped students and educators adapt to the new norms, and that have taken into account academic and industry relevance in language and communication pedagogy.

- New ideas, undergirded by theoretical principles, that are proposed to help students and educators adapt to the new norms.

Associate Professor LEE Kooi Cheng, Director, Centre for English Language Communication

DIGITAL TOOLS FOR PROMOTING SOCIAL READING

Tamara TATE & Mark WARSCHAUER

Abstract

We know that students benefit from social learning: collaboration can help students process and understand new information, see different perspectives, and create a community of learners. However, reading in undergraduate classes is often a solitary activity. Annotation has long been known as a way to support reflective reading. Recently available social e-reading tools now allow a whole class of students to collectively annotate the same document. During social annotation, students simultaneously access and mark digital texts and leave comments and questions for each other, creating an anchored context for conversation. Social annotation improves learning by supporting self-regulation, increasing engagement, providing scaffolding for improved reading comprehension, and promoting deep thinking. While useful for all students, social annotation may be especially helpful for English learners and other students not studying in their primary language, allowing them to access the same materials as peers with the provided scaffolding. These positive outcomes occur when social annotation is well integrated into instruction. When it is too complicated, confusing, or buggy to access and use, it can distract students and actually harm their language and literacy development. Research on the impact of social annotation on learning processes and outcomes will be synthesized, including implications for use of these tools in English language teaching. We will then discuss a case study of the use of social annotation throughout a graduate school course, along with suggestions for implementation.

Keywords: Reading, Social Annotation, English learners, Second language learning

INTRODUCTION

We know that students benefit from social learning. Collaboration can help students process and understand new information, see different perspectives, and create a community of learners (Tate & Warschauer, 2022; Mendenhall & Johnson, 2010). However, reading in undergraduate classes is often a solitary activity, done (or perhaps more often not done) prior to class. If students have not actively engaged with the reading materials prior to class time, the ensuing synchronous class time discussion can be unproductive, with the instructor forced to lecture on material that should have been learned prior to class or skip the planned content. What can instructors do to encourage and support student reading prior to class? Can students prepare asynchronously and digitally, reading in a reflective manner that is visible to the instructor?

One way readers interact with texts is through annotation. Using a pencil, pen, or perhaps post-it note, students have long used annotations to note important information, raise questions, and reflect on what they are reading. Unfortunately, these handwritten notes are clunky and hard to navigate, group, or otherwise consolidate. In addition, the notes are inaccessible to their classmates and instructors. No one is there to answer the question the student may have noted. The inaccessibility of handwritten annotations has fostered an interest in digital annotations, which allow students and teachers to more easily engage in activities like chunking or commenting on text. But as we know, learning – and especially language learning – is more powerful when it is social. And that is the principle behind a recent set of tools for social annotation, which allow groups of learners and teachers to annotate texts together. There are a number of software products for social annotation, with the two best known being Perusall and Hypothes.is. We have used Perusall successfully in our own undergraduate and graduate courses, and also reviewed the literature on its use, particularly in second language classrooms. We will outline the current state of research on social annotation and present a case study of our use in a graduate course to inform others who may be interested in trying social annotation in their courses.

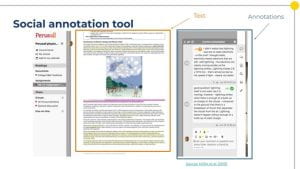

During social annotation, students simultaneously access and mark digital texts and leave comments and questions for each other (Morales et al., 2022; Figure 1). Annotating directly on a text creates what scholars call an anchored context for conversation (Brown & Croft, 2020). Students can ask about specific language issues or share personal responses right next to the portions of the text that they highlight. The instructor can also prime the discussion, either by raising questions for students to consider or by responding to student comments.

Figure 1. Example of annotations in Perusall

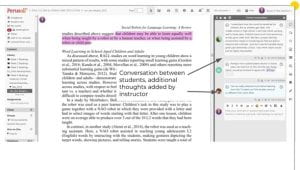

Below is an example of how we have used social annotation in one of our own graduate classes on literacy and technology. A student raised a comment on the text, and then other students and the instructor have responded as well (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Annotations in conversation with each other

Social annotation software also comes with a wide range of tools for instructors. Perusall, for example, has an automated student scoring mechanism that takes into account the quantity and quality of student postings, and also provides student confusion reports and student activity reports to faculty based on overall class comments. More broadly, social annotation software makes students’ thoughts and questions visible during the reading process, which can help instructors better understand and support their learning trajectories.

RESEARCH BASIS

Social annotation has been shown to improve student learning (Cadiz et al., 2000; Nokelainen et al., 2003; Marshall and Brush, 2004; Ahren, 2005; Gupta et al., 2008; Robert, 2009; Su et al., 2010). Social annotation improves learning by supporting self-regulation, increasing engagement, providing scaffolding for improved reading comprehension, and promoting deep thinking. While useful for all students, social annotation may be especially helpful for English learners and other students not studying in their primary language, allowing them to access the same materials as peers with the provided scaffolding. We discuss each of these briefly, with a deeper discussion of scaffolding for reading comprehension in order to highlight ways in which social annotation may be of particular benefit to English learners or students reading in their non-primary language.

Self-Regulation

One-way social annotation improves student learning is by increasing accountability for student reading, thus increasing student completion of reading assignments from reported levels of 60-80% not reading assigned texts to 90-95% completion of assigned readings prior to class (Miller et al., 2018). Social annotation tools also may increase the amount of time students spend reading (Miller et al., 2018), though we caution that this finding does not reflect off-line reading time nor account for the quality of the time spent online. Online social annotation also has a benefit over discussion forums, often used to discuss class readings–the online annotations are fixed in the text, rather than digressing as discussion threads often do. This may help students stay more grounded in the text and task at hand (Sun & Gao, 2017).

Engagement

Instructors report substantial student motivation and engagement when using social annotation (d’Entremont & Eyking, 2021). Social annotation has even been seen to promote affective as well as cognitive engagement with texts (Traester et al., 2021). Social annotation makes the learning experience more interactive (Chen et al., 2014; Su et al., 2010) and creates a sense of community (Solmaz, 2020; Allred et al., 2020) and a relaxed pedagogical setting suitable for educational risk taking (Solmaz, 2021). One researcher found that “More than 60% of students said annotating helped them feel connected to their peers, and almost 70% said it increased the amount of interaction they had with others in the class (Novak et al., 2012).

Scaffolding for Reading Comprehension

Reading comprehension abilities improve with the use of social annotations (Sun & Gao, 2017; Chang & Hsu, 2011; Chen et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2014) for both first and second language students (Sun & Gao, 2017). Social annotation distributes second language learners’ cognitive load (Blyth, 2014) and offers the opportunity for individualized reading support (Tseng et al., 2015).

Online annotations are often characterized as improving three levels of comprehension: surface-based, text-based, and situation-based (Tseng et al., 2015). Surface-based comprehension means the students have sufficient grammatical knowledge and vocabulary to decode the meaning of the text. Text-based comprehension is a layer deeper and occurs when students cannot only decode the text, but can reproduce the essential information from the text. Finally, in the situation-based comprehension level students can situate the textual information in other knowledge and integrate it in a coherent manner (Tseng et al., 2015). An instructor can cause students to use the social annotation tool to support these levels of comprehension and both instructors and peers can provide scaffolding through annotation of the text under study. For example, instructors can prompt students to summarize what they have read at various points in the text, students can add definitions for words that they had to look up, and both instructors and peers can add background information that makes the text more understandable or suggest linkages to other class content (d’Entremont & Eyking, 2021).

Social annotation not only provides an interactive reading context for students with support for comprehension of the specific passage under study, but also opportunities to model and practice effective reading strategies (Bahari et al., 2021). Students using social annotation have improved their use of reading strategies (Chen & Chen, 2014). Collaborative annotation also provides students with the opportunity to draw others’ attention to specific content; organize, index, and discuss new information; and correct misunderstandings (d’Entremont & Eyking, 2021; Razon et al., 2012).

In one example, Solmaz (2021) carried out a study of social annotation in an English class of college students in Turkey. By analyzing students’ annotations, he found contextual affordances were facilitated through digital social reading practices such as asking comprehension questions, expanding content through questions, integrating knowledge from other sources, exploring additional information, activating background knowledge, and providing additional contextual information. Text-to-text connections are a powerful practice for developing contextual knowledge (Adams & Wilson, 2021). Linguistic affordances of digital collaborative reading practices were helpful for skills in areas such as reading, vocabulary, grammar, and writing (Solmaz, 2021). Specifically, students could emphasize the function of a grammatical structure, share grammar-related notes, ask structure centered questions, provide vocabulary-related explanations, ask questions about lexical context, and add multimedia representing lexical items.

Promoting Deep Thinking

Social annotation promotes deeper thinking by encouraging students to actively reflect on the text as they make annotations. Social annotation supports reinforcement of existing knowledge and the contextual integration of new knowledge (Glover et al., 2007). Social annotation helps students to build their knowledge in new domains by making and drawing on connections within texts together with their classmates and instructor. The act of annotation causes a reader to think about the content that they are about to write in order to ensure both the relevance and the merit of their thoughts before sharing them with their instructor and peers (Glover et al., 2007). It allows students time and space to consider rhetorical choices, reflect, think, and gather evidence prior to engaging in a discussion of the text (Chen & Chiu, 2008). In addition, the social affordances of digital collaborative practices include the recognition of multiple perspectives (Solmaz, 2021), which in turn scaffolds more critical thinking. Students report deeper learning than in typical class discussions of reading (d’Entremont & Eyking, 2021).

And a Word of Warning

All of these positive affordances have been reported multiple times. And we have noted them in our own instruction. However, a word of warning. These positive outcomes occur when social annotation is well integrated into instruction. When it is too complicated, confusing, or buggy to access and use, it can distract students and actually harm their language and literacy development (Archibald, 2010). It is important for instructors to be intentional about which digital tools and when they implement them in courses, since each tool has a learning curve. Thus, “we recommend purposeful implementation based on the accessibility of the technology, how effectively it addresses specific learning goals, and how well its intended purposes fit the needs of the students” (Allred et al, 2020, p. 238). Indeed, students report that the annotations take a great deal of time (d’Entremont & Eyking, 2021) and significant instructor time is required for integration. A final caveat, social annotation may only work when it is used in a collaborative mode, rather than as an individual, so the context in which it is employed is of critical importance (Johnson et al., 2010; Hwang et al., 2007).

CASE STUDY

We used social annotation at a large research university in the southwestern United States. Our setting was a graduate course in literacy and technology taught by the second author with learning assistant support from the first author. The course was presented in hyflex mode, with students having the option of participating in person or online, due to the ongoing pandemic. Each week students had three to four readings on the week’s topic, generally research articles. The class used the Canvas learning management system to host all course content.

The authors were interested in using social annotation for the course and investigated multiple platforms months prior to the start of the course. Perusall was selected because it was integrated with the Canvas learning platform, had been successfully used by other faculty members at the institution who offered suggestions and support, was free, and allowed annotation on uploaded pdfs of articles so that all reading could be made available on the platform without charge to students.

The authors explained in the first course announcement that they would be using social annotation and uploaded a screencast explaining how students would access and use the platform. The use of social annotation was positioned as an experiment and student feedback was encouraged. Indeed, use of the tool was iteratively revised over the course of the quarter based on student feedback. For example, after the first week, the instructor required that student readings be done by the night before class in order to allow the instructor to review the annotations prior to class because the annotations had proven so useful for creating engaging, deep class discussions. Students were also no longer put in groups to comment, preferring to have the entire class in the same group so they could see one another’s comments. Although we had read that groups of more than 5 commenting on readings could become chaotic, we did not find this to be a problem in our class of approximately 10 people.

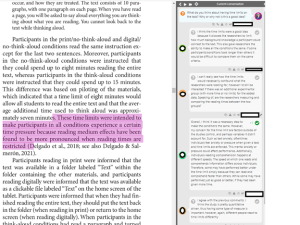

The instructor took various roles during the quarter. Especially in the early weeks, one of the authors would post comments, suggest questions, and make linkages between readings for students to consider. See Figure 3 for an example of an instructor asking a specific question and student replies.

Figure 3. Instructor and student discussion of text

In later weeks, less prompting by the instructors was needed and students were independently annotating with comments like, “This reminds me of a conversation we had in class about …” in which they connected the text to an earlier class discussion. They also became confident in clarifying and refining each other’s annotations as time went on and in stating “I’m a little confused by this…” Posts became more conversational over time, for example “I was wondering the same thing!” One of our students even tried to regularly post memes as part of their annotations, adding some multimodality (and humor) to the readings.

One of the authors would also try to check in on the ongoing status of annotations during the week (generally the 48 hours before readings were due) to answer questions, correct misconceptions, and generally become aware of topics of interest that could be addressed in the upcoming synchronous class. Prior to class, the instructor would find annotations that would serve as useful discussion starters in class, often copying the text of the annotation to the week’s slides and letting the student know that their annotation would be part of the class discussion. Here’s an example (Figure 4) when the instructor had reviewed students’ comments and made notes on them during her slide presentation so she could call on the students to further elaborate during class.

Figure 4. Class slide with excerpts from reading annotations to prompt student in class discussion

This process was time intensive, but led to very rich discussions in which all students could participate. Even students who might not prefer speaking in class were more likely to expand on thoughts they had been able to put down in the privacy of their reading without time constraints. We think the ability to think through their responses prior to class, coupled with the foreknowledge they would be called on to elaborate, allowed students (including those who were multilingual or had learning disabilities) to fully participate in ways that cold-calling on them would not.

We do note that there are students for whom the social annotation process hampers their reading for a variety of reasons, and for such situations, alternative arrangements may be appropriate (e.g., a 1-page reading response discussing the week’s readings). For some students with reading disabilities, the additional textual input from their peers may be too distracting for them to process. A student with social anxiety may be uncomfortable showing their thinking to their peers in the annotations. In these situations, the instructor can consult with the student, and possibly the disability resources on campus, to determine how to best structure the students’ learning. We have not seen research at this point that looks at the use of social annotation for neurodiverse populations, so instructors will need to creatively and compassionately address these issues as they arise.

Grading of the social annotations each week was awkward. Perusall will do automatic scoring of annotations based on quantity of annotations, perceived quality of annotations, amount of time recorded reading on the Perusall site, and other factors. The factors can be adjusted by the instructor, and the settings used by the authors were based on suggestions from other faculty members. However, since students were not required to read on Perusall (they could read offline and simply add annotations after reading) and the AI used imperfectly judged quality, the authors repeatedly assured students that reading grades would be adjusted at the end based on feedback from students. To allow students to provide this feedback, an assignment was created on Canvas giving each student the opportunity to give the instructor their own self-assessment of their reading/reflection in the course, giving themselves a grade of 0-100. The instructor took these ratings into consideration and revised the automatic grading scores as deemed appropriate. 30% of the students chose to provide feedback, one noting that a score for a week had not been corrected on Canvas, but Perusall was “good overall,” and others explaining why they deserved higher grades and noting their appreciation for the opportunity to provide feedback. We recommend careful consideration of giving appropriate credit for the work involved in online social annotation and not de-motivating students with excessively narrow requirements for grading. As noted in a recent Opinion piece,

An engaging technology-aided activity guided by an instructor might feel like an invasion of privacy for students hesitant to make private thoughts public. An instructor encouraging open-mindedness can make students feel like they’re being watched. An over-reliance on technology assessing participation can make students feel like homework compliance is valued more highly than comprehension and the substance of their responses. (Cohn & Kalir, 2022)

CONCLUSION

If deep reading of a select amount of text is necessary in a course (as compared to skimming a large number of texts), instructors should consider the use of social annotation. Social annotation can help level the playing field for students who will be reading in a language other than their primary language. It may also support students with learning disabilities or provide important interactivity and social connection in an online course. We found active use of social annotation by instructors and students greatly enhanced the quality and breadth of in-class discussions. However, instructors should select their platform with care to ensure that it is easy to use and well-integrated with their course platform. They need to provide clear instructions and ensure that all students are comfortably able to interact with the social annotation tool. Course readings should be reduced in number to account for the additional time and effort to be put into more thoroughly reading a limited number of texts. The instructor should plan to use the annotations actively, so that students are not shouting into a void, but rather their voices are amplified and discussed in class or seen and discussed by the instructor in the annotations. Students should receive appropriate credit in the grading scheme for their work reading the texts and the grading rubric should be transparent.

In summary, social annotation is similar to many other educational technologies we have researched (see, e.g., Grimes & Warschauer, 2010; Tate, et al, 2019; Warschauer, 1996; Warschauer, 2011) – not a magic bullet to transform learning, but a valuable tool if effectively integrated into instruction. Educators who design learning experiences that build on both the affordances of the technology and the context of their classes can expect corresponding benefits for their students in both engagement and learning.

Acknowledgment: This paper draws on the keynote presentation made by the second author on social reading at the 6th CELC (e)Symposium, May 30, 2022.

REFERENCES

Adams, B. & Wilson, N. S. (2020). Building community in asynchronous online higher education courses through collaborative annotation. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(2).

Ahren, T. C. (2005). Using online annotation software to provide timely feedback in an introductory programming course. Paper Presented at the 35th ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, Indianapolis, IN. Available at: http://www.icee.usm.edu/icee/conferences/FIEC2005/papers/1696.pdf

Allred, J., Hochstetler, S., & Goering, C. (2020). “I love this insight, Mary Kate!”: Social annotation across two ELA methods classes. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 20(2), 230-241.

Archibald, T. N. (2010). The effect of the integration of social annotation technology, first principles of instruction, and team-based learning on students’ reading comprehension, critical thinking, and meta-cognitive skills. The Florida State University.

Bahari, A., Zhang, X., & Ardasheva, Y. (2021). Establishing a computer-assisted interactive reading model. Computers & Education, 172, 104261.

Blyth, C. (2014). Exploring the affordances of digital social reading for L2 literacy: The case of eComma. Digital Literacies in Foreign and Second Language Education, 12, 201-226.

Brown, M. & Croft, B. (2020). Social annotation and an inclusive praxis for open pedagogy in the college classroom. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2020(1), 8. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jime.561

Cadiz, J. J., Gupta, A., & Grudin, J. (2000). Using web annotations for asynchronous collaboration around documents, in Proceedings of CSCW 00: The 2000 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (Philadelphia, PA: ACM), 309–318.

Chang, C. K., & Hsu, C. K. (2011). A mobile-assisted synchronously collaborative translation–annotation system for English as a foreign language (EFL) reading comprehension. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 24(2), 155-180.

Chen, C. M., & Chen, F. Y. (2014). Enhancing digital reading performance with a collaborative reading annotation system. Computers & Education, 77, 67-81.

Chen, C. M., Wang, J. Y., & Chen, Y. C. (2014). Facilitating English-language reading performance by a digital reading annotation system with self-regulated learning mechanisms. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 17(1), 102-114.

Chen, G., & Chiu, M. M. (2008). Online discussion processes: Effects of earlier messages’ evaluations, knowledge content, social cues and personal information on later messages. Computers & Education, 50(3), 678-692.

Chen, J. M., Chen, M. C., & Sun, Y. S. (2010). A novel approach for enhancing student reading comprehension and assisting teacher assessment of literacy. Computers & Education, 55(3), 1367-1382.

Cohn, J., & Kalir, R. (2022, April 11). Opinion: Why we need a socially responsible approach to “social reading.” The Hechinger Report. Retrieved from https://hechingerreport.org/opinion-why-we-need-a-socially-responsible-approach-to-social-reading/

d’Entremont, A. G. & Eyking, A. (2021). Student and instructor experience using collaborative annotation via Perusall in upper year and graduate courses. Proceedings of the Canadian Engineering Education Association (CEEA-ACEG) Conference.55(3), 1367-1382.

Glover, I., Xu, Z., & Hardaker, G. (2007). Online annotation–Research and practices. Computers & Education, 49(4), 1308-1320.

Grimes, D., & Warschauer, M. (2010). Utility in a fallible tool: A multi-site case study of automated writing evaluation. Journal of Technology, Language, and Assessment 8(6), 1-43.

Hwang, W. Y., Wang, C. Y., & Sharples, M. (2007). A study of multimedia annotation of Web-based materials. Computers & Education, 48(4), 680-699.

Johnson, T. E., Archibald, T. N., & Tenenbaum, G. (2010). Individual and team annotation effects on students’ reading comprehension, critical thinking, and meta-cognitive skills. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1496-1507.

Marshall, C. C., & Brush, A. J. B. (2004). Exploring the relationship between personal and public annotations. Proceedings of JCDL’04: The 2004 ACE/IEEE Conference on Digital Libraries (Tucson, AZ), 349–357.

Mendenhall, A., & Johnson, T. E. (2010). Fostering the development of critical thinking skills, and reading comprehension of undergraduates using a Web 2.0 tool coupled with a learning system. Interactive Learning Environments, 18(3), 263-276.

Miller, K., Lukoff, B., King, G., & Mazur, E. (2018). Use of a social annotation platform for pre-class reading assignments in a flipped introductory physics class. Frontiers in Education, 2018(3). doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00008

Morales, E., Kalir, J. H., Fleerackers, A. & Alperin, J.P. (2022). Using social annotation to construct knowledge with others: A case study across undergraduate courses [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. F1000Research 2022, 11:235 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.109525.2

Nokelainen, P., Kurhila, J., Miettinen, M., Floreen, P., & Tirri, H. (2003). Evaluating the role of a shared document-based annotation tool in learner-centered collaborative learning. Proceedings of ICALT’03: the 3rd IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (Athens), 200–203.

Novak, E., Razzouk, R., & Johnson, T. E. (2012). The educational use of social annotation tools in higher education: A literature review. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(1), 39-49.

Razon, S., Turner, J., Johnson, T. E., Arsal, G., & Tenenbaum, G. (2012). Effects of a collaborative annotation method on students’ learning and learning-related motivation and affect. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(2), 350-359.

Robert, C. A. (2009). Annotation for knowledge sharing in a collaborative environment. Journal of Knowledge Management, 13, 111–119. doi:10.1108/13673270910931206

Solmaz, O. (2020). The nature and potential of digital collaborative reading practices for developing English as a foreign language. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching (IOJET), 7(4). 1283-1298. http://iojet.org/index.php/IOJET/article/view/763

Solmaz, O. (2021) The affordances of digital social reading for EFL learners: An ecological perspective. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning (13) 2.

Su, A. Y. S., Yang, S. H., Hwang, W. Y., & Zhang, J. (2010). A web 2.0-based collaborative annotation system for enhancing knowledge sharing in collaborative learning environments. Computer Education, 55, 752–766. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2010.03.008

Sun, Y., & Gao, F. (2017). Comparing the use of a social annotation tool and a threaded discussion forum to support online discussions. The Internet and Higher Education, 32, 72-79.

Tate, T, & Warschauer, M. (2022): Equity in online learning. Educational Psychologist, DOI: 10.1080/00461520.2022.2062597

Tate, T. P., Collins, P., Xu, Y., Yau, J. C., Krishnan, J., Prado, Y., Farkas, G., & Warschauer, M. (2019). Visual-syntactic text format: Improving adolescent literacy. Scientific Studies of Reading, 23(4), 287-304.

Traester, M., Kervina, C., & Brathwaite, N. H. (2021). Pedagogy to Disrupt the echo chamber: Digital annotation as critical community to promote active reading. Pedagogy, 21(2), 329-349.

Tseng, S. S., Yeh, H. C., & Yang, S. H. (2015). Promoting different reading comprehension levels through online annotations. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(1), 41-57.

Warschauer, M. (1996). Motivational aspects of using computers for writing and communication. In Warschauer, M. (Ed.), Telecollaboration in foreign language learning (pp. 29-46). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Second Language Teaching and Curriculum Center.

Warschauer, M. (2011). Learning in the cloud: How (and why) to transform schools with technology. New York: Teachers College Press.

Tamara TATE is a Project Scientist at the University of California, Irvine, and Assistant Director of the Digital Learning Lab. She leads the Lab’s work on Investigating Digital Equity and Achievement (IDEA), partnering with school districts, universities, nonprofit organizations, media and tech developers, and others in iterative development and evaluation of digital and online tools to support teaching and learning. She received her B.A. in English and her Ph.D. in Education at U.C. Irvine and her J.D. at U.C. Berkeley.

Mark WARSCHAUER is Professor of Education at the University of California, Irvine, where he directs the Digital Learning Lab. Professor Warschauer has made foundational contributions to language learning through his pioneering research on computer-mediated communication, online learning, technology and literacy, laptop classrooms, the digital divide, automated writing evaluation, visual-syntactic text formatting, and, most recently, conversational agents for learning. His dozen books and more than 200 papers have been cited more than 40,000 times, making him one of the most influential researchers in the world in the area of digital learning. He is a fellow of the American Educational Research Association and a member of the National Academy of Education.

FUTURE-LOOKING PRINCIPLE-BASED CURRICULUM INNOVATIONS

Julia CHEN

Abstract

The pandemic has accelerated the creation and adoption of curriculum innovations. This keynote address will present and discuss innovations in discipline-related English language training both within and outside the curriculum that were created for two purposes: to help students improve their English and to ensure they spend time outside of class on English language learning. Aspects such as curriculum design, development, implementation, and evaluation will be explored; the considerations that deserve attention will be highlighted. References will be made to some theoretical frameworks, such as the Community of Inquiry approach (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000), the three-phase process of change via initiation, implementation, and institutionalisation (Fullan, 1991), and the ADRI approach, as well as to empirical studies that employed big data learning analytics triangulated with qualitative methods.

Keywords: Pandemic, VUCA, principle-based, curriculum innovation, new literacies, English Across the Curriculum

INTRODUCTION

Higher education (HE) around the world has been facing unprecedented challenges in the last few years. The onset of COVID-19 necessitated a radical shift from face-to-face lessons to emergency remote learning and teaching (L&T) within a few weeks; and as COVID-19 continued, online L&T has become the norm in many higher education institutions (HEIs). Further, the world is facing an era of VUCA, an acronym first used by the US army, standing for volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity. The Oxford University Executive Education program has a similar acronym, which is TUNA: turbulence; uncertainty; novelty; ambiguity. Both acronyms reflect a complex and ambiguous world in which unpredictable changes, rapid upheavals, and new elements are emerging. While the day-to-day aspects of education in the COVID (or post-COVID) era, such as engaging students in blended courses and designing online assessment, are being addressed, HEIs should also be aware of how a VUCA or TUNA world will form the next generation and consider ways to adapt or re-conceptualise education to prepare students for the future.

CHANGES TO HE CAUSED BY THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The COVID-19 pandemic has been called a perfect storm given the impact it has had on traditional methods of teaching, learning, training, and education (Sutton & Jorge, 2020, p. 125). The pandemic has forced all parties into the middle of a typical battlefield as “it unmasked the hidden fragilities of the system and vulnerabilities of all its stakeholders”, requiring an abrupt and urgent need to change over a very short period of time (Domingo-Maglinao, 2021, p. 803). Although there are diverse views about the effects of COVID on HE, academics agree that teachers and students should try to “achieve a mutual and meaningful collaborative learning and social space” (Neuwirth et al., 2021, p. 154), in which “learning activities involving digital technologies reflect cognitive processes of students” (Sailer, 2021, p.1). In this way, the pandemic can be viewed positively as it has triggered a transformative process that builds on the insights of the past two years, seeking to engage students in “active, constructive, and interactive learning activities” (Sailer, 2021, p.5), and “ease adherence to new processes that foster sustainable development in higher education” (Sá & Serpa, 2020, p.13).

Some, however, have observed that rather than having a transformative process on education, the pandemic has brought a change to online learning, teaching and assessment (LTA) which has simply “reduced [it] to the fulfilment of rudimentary technical functions” (Watermeyer et al., 2020, p. 631). When HEIs “rethink and reinvent learning environments … that expand … and complement students’ learning” (Tejedor et al., 2020, p. 14), a key to determining whether the changes are rudimentary or transformative may lie with their teachers. Teachers’ responses to the transition to online teaching have been categorised under three profiles: those who have: 1) “actively use new methods and software thoughtfully and managed constraints, and indicated sustainable changes to their way of teaching”, 2) “engaged moderately in making changes, experienced challenges and were less optimistic about their efforts”, and 3) “reported various constraints, that hindered teaching practices and successful delivery of teaching” (Damşa et al., 2021, p. 13). Thus, HEIs should encourage staff, whether they are innovators, early adopters, or laggards (Rogers, 2003), to make the most of the insights and experiences gained in the last two years.

DEVELOPMENT OF TECHNOLOGY-ENHANCED LEARNING AND MULTIMODAL LITERACIES

While COVID-19 has highlighted the need to improve remote teaching with well-planned digital learning environments, the advent of new technologies has given rise to innovative teaching activities that require a certain degree of digital competence from both the teacher and the student. As early as 2006, the European Commission had identified digital competence, communication in the mother tongue, and competence in foreign languages as three of the eight key life skills; however, a review of the literature reveals that the majority of HEI teachers and students are at only “a basic level of digital competence” (Zhao et al., 2021, p. 1).

Rapid technological advances have brought about unprecedented effects on education. Using advanced technology has become a normal, if not required part teaching in HEIs, with Learning Management Systems (LMSs) being a major platform for learning, academic discussions, and archiving of course materials (Navarro et al., 2021). The use of the LMS, other elearning methods, and mobile-assisted learning have prompted studies on task-technology fit, learning styles, and influences on the elearning process (Tan et al., 2018; Dolawattha et al., 2022). One of the notable challenges is the lack of interaction in synchronous lessons and asynchronous activities (Vlachopoulos & Makri, 2019). This difficulty serves as a timely reminder that the design of courses, whether in face-to-face, fully online, or blended mode, should attend to the interplay between three presences: cognitive, teacher, and social, as presented in the Community of Enquiry framework (Garrison et al., 2000; Tyrvainen et al., 2021; Goggins & Hajdukiewicz, 2022).

Rapidly changing environments have also re-conceptualised communication. No longer mono-directional in the form of writing (e.g., via email) or speaking (e.g., in presentations), communication is an organised and purposeful multi-dimensional mixture of connected and iterative concepts (Martin & Lambert, 2015), and has become “increasingly complex, multimodal, and … inextricably linked with the use of technology” (McCallum, 2021, p. 616). HE students should be taught to make “coherent use” of different modes (Ruiz-Madrid, & Valeiras-Jurado, 2020, p. 44). Multimodal learning design has been found to promote “students’ communication of their understanding of STEM concepts” and their acquisition of “multiple disciplines” (Gray et al., 2019, p. 9).

LANGUAGE CURRICULUM DESIGN THAT PREPARES STUDENTS FOR THE FUTURE

The volatility sparked by the pandemic, rapid technological advances, and new literacies emerging in the digital age, demand a serious re-consideration of whether our present form of education is appropriately and adequately preparing students for the future. Concurrently, educators need to consider how innovations can be incorporated into our courses, curriculums, and co-curricular provisions to train students to thrive in a VUCA world. Accordingly, I propose addressing VUCA with education supported by the following underpinning pedagogic principles: familiarisation with new competencies, authentic engagement with learning and thinking amid changing scenarios, and empowerment of students in blended learning environments.

While academic literacies are important and should continue to be a main component of language courses, some of the new literacies and genres should also be included to familiarise students with the competencies they are expected to develop (Elola & Oskoz, 2017). The concept of literacy has expanded to include different modes of meaning-making and communication. As defined by UNESCO (2021), “literacy is now understood as a means of identification, understanding, interpretation, creation, and communication in an increasingly digital, text-mediated, information-rich and fast-changing world.” The aim of HEIs should be to develop students’ ability to communicate and negotiate successfully whatever the mode: written or spoken, text or visual, and in-person or virtual. Developing students’ multiple literacies should be coordinated at the institutional level and the language centre level. At the former level, the development of new literacies should be aligned with the attributes that the HEIs would want to see in their graduates (e.g., effective multi-dimensional communication); thus, they need to be incorporated into institutes’ strategic plans to ensure students do develop those attributes.

At the centre level, some teachers are beginning to include the use of infographics in their courses enabling them to visualise their ideas, systematically present their information, and transfer their content from one mode (e.g., text) to another (graphics) (Sukerti & Sitawati, 2019]. Studies have shown the effect of infographics on enhancing student motivation and achievement (Ibrahem & Alamro, 2021; Kohnke et al., 2021). Another example concerns the focus of language teaching and assessment, where new literacies and competencies are built via the digital story, which is an example of assessment that develops both writing (i.e., composing) and speaking (i.e., audio/video presentation of stories) skills in a situated context, (e.g., topics related to the students’ major discipline). Using digital stories has also been found to increase student achievement and motivation (Aktas & Yurt, 2017). Other types of multi-literacy teaching foci and assessment include multi-modal proposals that have text, infographics and videos, and a critical synthesis and review of multimedia information from multiple sources to help students realise the relationship between, and the inter-dependence of, the various modes and the content expressed through them. One study showed that assignments that require the creation of multimodal portfolios can even engage at-risk students in multimodal thinking and the development of a critical stance (Lawrence & Mathis, 2020). At a more strategic level, language centres can plan which new literacies and competencies should be introduced in which courses, thus building a progressive pathway across the language centre courses in students’ undergraduate years.

Another underpinning educational principle is the active engagement of students in authentic learning and thinking amid changing scenarios, i.e., teachers should train students how to communicate using real-life situations. Courses that currently teach mono-directional communication (e.g., writing one email to a pseudo recipient) should be redesigned to focus on diverse communicative responses (e.g., replying to recipients of different status). Students can be given scenarios in which they do not compose only one response (e.g., proposal or email) or one presentation; instead, after their first response or speaking delivery, they can be required to give two or more different responses (e.g., a rejection or a sceptical response requesting clarification). These practices bring together linguistic and thinking skills, and provide opportunities for discussion of higher-level skills, such as register, criticality, defence, and succinctness. These learning activities promote thinking-based learning, where students articulate their thinking, strategise their responses, and translate those into writing (Swartz, 2008).

Communication is often a multi-stage process (Krishna & Morgan, 2004); thus, to prepare students for a VUCA world, courses should provide students with complex problems that require multiple stages of thinking and communication. In pairs or groups, students can be either given, or asked to establish, the parameters of stage 1 of a multi-stage scenario, then define the problem and attempt to address it. Then they can be given new factors and considerations that offset their previous solutions, forcing them to change their assumptions, re-think, re-plan, and re-communicate their ideas. Deep learning best occurs when some of the multi-stage scenarios end with only temporal solutions to bigger problems, or when tasks are designed in such a way that there are no optimal solutions or conclusion, which is often the case in real life.

The third underpinning pedagogic principle concerns empowering students in blended environments. Blended learning is likely to remain in the post-pandemic era, and flipped-classroom pedagogy will also probably continue. To increase student engagement and deepen their learning in blended and flipped classrooms, the Students-as-Partners or the Student-Staff-Partnership approach may be useful. “‘Students as Partners’ (SaP) in higher education re-envisions students and staff as active collaborators in teaching and learning” (Mercer-Mapstone et al., 2017, p.1). Students are engaged as partners in the co-creation of learning and teaching activities and materials. One possible way of integrating SaP and blended/flipped learning is for students to work in pairs/groups to design blended activities to be completed pre- or post-class; students can manage the first half hour of every lesson in which they conduct activities to check that their peers have completed and learnt from the flipped pre-class activities. Teachers can co-design with students “multiliteracies learning that meets them where they are” (Lim et al., 2021, p.109). These SaP arrangements empower students and have the potential to lead to deep, transformative learning (Healey et al., 2014).

Advanced technology also allows remote student-student partnerships in blended environments without geographical borders. The pandemic may have prevented HEIs from sending students on overseas learning trips; however, language courses are in an optimal position to bring the world to the classroom, enabling students to have an international experience. Collaborative online international learning (COIL) allows students from different countries to engage online in purposeful learning with “concrete goals and deliverables” (Mundel, 2020, p.114). In a COIL classroom, a class of students from another city join a local lesson online. Both classes of students can be engaged in cross-group discussions and assignments (such as comparative studies) that foster their intercultural communicative competence. Another type of assessment that suits COIL classes is problem-solving group activities (Jimenez & Kressner, 2021) that enrich students’ understanding of the thought processes and considerations of different cultures.

Blended learning encourages learning beyond the classroom and outside the formal curriculum. Due to a typically packed curriculum in undergraduate programmes, the number of English language courses is limited, with none in many semesters, resulting in an understandably incomplete coverage of the disciplinary academic literacy needs of students. Further, if an HEI provides generic academic English courses to students from all departments, those courses cannot cover highly specific academic genres, such as laboratory report writing. The English Across the Curriculum (EAC) initiative, based on the Writing Across the Curriculum model in North America, has identified these learning gaps and offers language learning resources and support outside the formal language curriculum (Chen & Morrison, 2021). In EAC, English teachers and discipline faculty work together to address students’ disciplinary literacy needs by offering timely English tips and learning activities that align with the language skills needed for specific assignments (Chen, Chan, & Ng, 2021), such as laboratory reports, medical incident reports, and product promotion. Textual analyses of students’ writing and speaking performances have been conducted to enable the production of support materials that target weaknesses, e.g., research mapping (Chen et al., 2021). The resources that are produced for students can be in multi-modal format and delivered to students via multiple channels using different platforms, including the Learning Management System or mobile applications, to cater for ubiquitous learning.

ENDING REMARKS

Rather than viewing VUCA negatively and avoiding its teaching repercussions, HEIs should train students to face VUCA and embrace its four aspects as critical processes that are present in any system that grows and evolves. Indeed, “the forces outlined in the VUCA model are beginning to wend their way into the rarefied environment of academe and are necessitating an existential reappraisal of higher educational institutions” (Stewart et al., 2016, p. 242). The pandemic has been a very difficult period, but it has also accelerated exciting changes in education while challenging academics to think strategically about the future of education, which includes the shaping of language education that reaches so many students every year. With strong underpinning philosophies and teamwork, HEIs and language centres need to step up to the challenge and make educational decisions that are compatible with sound pedagogic principles. The future may not be friendly to the unprepared; however, with determination and agility, language educators can introduce quality enhancement to their courses and programmes and develop in students a “futures literacy” (Miller, 2018) and a future-oriented mindset.

REFERENCES

Aktas, E., & Yurt, S. U. (2017). Effects of digital story on academic achievement, learning motivation and retention among university students. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(1), 180-196. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n1p180

Chen, J. & Morrison, B. (2021). Introduction. In B. Morrison, J. Chen, L. Lin, & A. Urmston (Eds.), English across the curriculum: Voices from around the world (pp. 3-14). WAC Clearinghouse. https://doi.org/10.37514/INT-B.2021.1220.1.3

Chen, J., Chan, C., Man, V., & Tsang, E. (2021). Helping students from different disciplines with their final year/capstone project: Supervisors’ and students’ needs and requests. In B. Morrison, J. Chen, L. Lin, & A. Urmston (Eds.), English across the curriculum: Voices from around the world (pp. 91-106). WAC Clearinghouse. https://doi.org/10.37514/INT-B.2021.1220.2.05

Chen, J., Chan, C., & Ng, A. (2021). English across the curriculum: Four journeys of synergy across disciplines and universities. In H. Lee, & B. Spolsky (Eds.), Localizing global English: Asian perspectives and practices (pp. 84-103). Oxon: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003082705

Damşa, C., Langford, M., Uehara, D., & Scherer, R. (2021). Teachers’ agency and online education in times of crisis. Computers in Human Behavior, 121, 106793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106793

Dolawattha, D., Premadasa, H., & Jayaweera, P. (2022). Modelling the influencing factors on mobile learning tools. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 17(4), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJICTE.20211001.oa6

Domingo-Maglinao, M. L. P. (2021). Leading change in a 150-year-old medical school: Overcoming the challenges of a VUCA world amidst a 21st century pandemic. Journal of Medicine, The University of Santo Tomas, 5(2), 802-812. https://doi.org/10.35460/2546-1621.2021-0159

Elola, I., & Oskoz, A. (2017). Writing with 21st century social tools in the L2 classroom: New literacies, genres, and writing practices. Journal of Second Language Writing, 36, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2017.04.002

Goggins, J., & Hajdukiewicz, M. (2022). The role of community-engaged learning in engineering education for sustainable development. Sustainability, 14, 8208. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138208

Gray, P., Germuth, A., MacNair, J., Simpson, C., Sowa, S., van Duin, N., & Walker, C. (2019). A new paradigm for STEM learning and identity in English language learners: Science translation as interdisciplinary, multi-modal inquiry. Journal of Interdisciplinary Teacher Leadership, 4(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.46767/kfp.2016-0027

Ibrahem, U. M. & Alamro, A. R. (2021). Effects of infographics on developing computer knowledge, skills and achievement motivation among Hail University students. International Journal of Instruction, 14(1), 907-926. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2021.14154a

Jiménez, J. L., & Kressner, I. (2021). Building empathy through a comparative study of popular cultures in Caracas, Venezuela, and Albany, United States. In M. Satar (ED.), Virtual exchange: Towards digital equity in internationalisation (pp.113-127). Research-publishing.net. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2021.53.1294

Kaczorowski, T. L., Kroesch, A. M., White, M., & Lanning, B. (2019). Utilizing a flipped learning model to support special educators’ mathematical knowledge for teaching. The Journal of Special Education Apprenticeship, 8(2), 1-15. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1231821.pdf

Kohnke, L., Jarvis, A., & Ting, A. (2021). Digital multimodal composing as authentic assessment in discipline-specific English courses: Insights from ESP learners. TESOL Journal, 12, e600. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.600

Krishna, V., & Morgan, J. (2004). The art of conversation: eliciting information from experts through multi-stage communication. Journal of Economic Theory, 117(2), 147-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jet.2003.09.008

Lawrence, W. J., & Mathis, J. B. (2020). Multimodal assessments: Affording children labeled ‘at-risk’ expressive and receptive opportunities in the area of literacy. Language and Education, 34(2), 135-152. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2020.1724140

Lim, F. V., Weninger, C., & Nguyen, T. T. H. (2021). “I expect boredom”: Students’ experiences and expectations of multiliteracies learning. Literacy, 55(2), 102-112. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12243

Martin, N. M., & Lambert C. S. (2015). Differentiating digital writing instruction: The intersection of technology, writing instruction, and digital genre knowledge. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 59(2), 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.435

McCallum, L. (2021). The development of foundational and new literacies with digital tools across the European higher education area. Aula Abierta, 50(2), 615-624. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.50.2.2021.615-624

Mercer-Mapstone, L., Dvorakova, S. L., Matthews, K. E., Abbot, S., Cheng, B., Felten, P., Knorr, K., Marquis, E., Shammas, R., Swaim, K. (2017). A systematic literature review of students as partners in higher education. International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3119

Miller, R. (Ed.). (2018). Transforming the future: Anticipation in the 21st century. UNESCO Publishing. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000264644

Mundel, J. (2020). International virtual collaboration in advertising courses. Journal of Advertising Education, 24(2), 112-132. https://doi.org/10.1177/109804822094852

Navarro, M. M., Prasetyo, Y. T., Young, M. N., Nadlifatin, R., & Redi, A. A. N. P. (2021). The perceived satisfaction in utilizing learning management system among engineering students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Integrating task technology fit and extended technology acceptance model. Sustainability, 13, 10669. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910669

Neuwirth, L. S., Jović, S., & Mukherji, B. R. (2021). Reimagining higher education during and post-COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 27(2), 141-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477971420947738

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations. (5th ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

Ruiz-Madrid, N. & Valeiras-Jurado, J. (2020). Developing multimodal communicative competence in emerging academic and professional genres. International Journal of English Studies, 20(1), 27-50. https://doi.org/10.6018/ijes.401481

Sá, M. J., & Serpa, S. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to foster the sustainable development of teaching in higher education. Sustainability, 12(20), 8525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208525

Sailer, M., Schultz-Pernice, Fischer, F. (2021). Contextual facilitators for learning activities involving technology in higher education: The Cb model. Computers in Human Behavior, 121, 106794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106794

Stewart, B., Khare, A., & Schatz, R. (2016). Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity in Higher Education. In O. Mack, A. Khare, A. Krämer, & T. Burgartz (Eds.), Managing in a VUCA World (pp. 241-250). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16889-0_16

Sutton, M. J. D., & Jorge, C. F. B. (2020). Potential for radical change in higher education learning spaces after the pandemic. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 3(1), 124-128. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2020.3.1.20

Swartz, R. J. (2008). Thinking-based learning. Educational Leadership, 65(5), 1-24. https://www.academia.edu/10626103/Thinking_Based_Learning

Tan, S. Z., Hassim, N., Jayasainan, S. Y., & Gan, P. C. K. (2018). Effects of task-technology fit and learning styles on continuance intention to use e-learning app. European Conference on e-Learning (pp. 539-546). https://www.proquest.com/conference-papers-proceedings/effects-task-technology-fit-learning-styles-on/docview/2154981970/se-2

Tejedor, S., Cervi, L., Pérez-Escoda, A., & Jumbo, F. T. (2020). Digital literacy and higher education during COVID-19 lockdown: Spain, Italy, and Ecuador. Publications, 8(4), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications8040048

Tyrvainen, H., Uotinen, S., & Valkonen, L. (2021). Instructor presence in a virtual classroom. Open Education Studies, 3, 132-146. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/edu-2020-0146/html?lang=en

UNESCO (2021). Literacy. https://en.unesco.org/themes/literacy

Vlachopoulos, D., & Makri, A. (2019). Online communication and interaction in distance higher education: A framework study of good practice. International Review of Education, 65, 605-632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-019-09792-3

Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., Knight, C., & Goodall, J. (2020). COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: afflictions and affordances of emergency online migration. Higher Education, 81, 623–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

Zhao, Y., Pinto Llorente, A. M., & Sánchez Gómez, M. C. (2021). Digital competence in higher education research: A systematic literature review. Computers & Education, 168, 104212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104212.

Associate Professor Julia CHEN is the Director of the Educational Development Centre at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Her research interests include English Across the Curriculum, leveraging technology for advancing learning and teaching, and using learning analytics for curriculum review and quality enhancement. She was the principal investigator of several large-scale government-funded inter-university projects on EAC and using technology for literacy development. Her work has been published in journals and edited collections. A two-time recipient of her university’s President Award for Excellent Performance, first in teaching and then in service, she was shortlisted for the Hong Kong UGC Teaching Award and by QS Quacquarelli Symonds for the Reimagine Education Learning Assessment Award. She is a Principal Fellow of Advance HE (PFHEA), and recently received the lifetime designation award of Distinguished Fellow from the Association for Writing Across the Curriculum. She has served on many education committees, as well as review boards in the US and East Asia.

DECOLONIZING LANGUAGE BELIEFS AND IDEOLOGIES IN ELT

Ruanni TUPAS

Abstract

The English Language Teaching classroom is not an isolated social vacuum but an institutional global(ised) space. Therefore, my talk centres on the coloniality of our beliefs and practices in ELT. While many argue that colonialism is a thing of the past, the discourses and practices associated with it continue to shape most, if not all, facets of the ELT profession. We refer to this condition as the coloniality of ELT where the practice of ELT is by itself deeply embedded within the structures and logics of (global) coloniality. Although I also problematise the many ways this lens is mobilised in teaching and research, I argue that attempts at transforming the ELT classroom must contend with its embeddedness within conditions of coloniality.

Keywords: ELT, language beliefs, coloniality, decolonization

INTRODUCTION

Why do we need to decolonize language beliefs and ideologies in English Language Teaching (ELT), and what does decolonizing entail? These are two intertwined questions which will be addressed in this paper. For the first one, it is because core language beliefs and ideologies which circulate in the field remain deeply colonial. For the second question, it entails more than just problematizing such beliefs and ideologies. We need to take control of the processes and infrastructures of knowledge production which perpetuate such beliefs and ideologies in the first place.

In practically all academic disciplines, especially in the social sciences and humanities, we have in recent years seen a “surge of decolonial debates” (Moghli & Kadiwal, 2021, p. 11). In the interrelated fields of applied linguistics and sociolinguistics and, more specifically, English Language Teaching (ELT), this is a much welcome development. More than three decades ago, Pennycook (1989) asserted that “ELT theories and practices that emanate from the former colonial powers still carry traces of those colonial histories” (p. 19). However, for most of the past three decades, the centrality of colonial questions has somehow been glossed over by work which focuses on celebrating English language users’ agency, creativity and so-called postcolonial resistance. While such agentive, creative and/or resistive use of English shows us that we are not “cultural dupes or passive puppets of an ideological order, or cogs in a mechanistic universe” (Morrison and Lui, 2000, p. 472), how it has been conceptualized is problematic. Agency has been overemphasized and decontextualized from the structure within which it (agency) is operationalized. The dominant academic rhetoric has been something like this: ‘It is true that there remain structures of domination in today’s world, but you see, speakers of English have also exercised their agency over these structures.’ The scholarly work then surfaces these instantiations of agency and sets aside the continuing conditions of domination and social inequality within which such agency is mobilized. This is the reason why, for some scholars, colonialism is a thing of the past or is now a side issue (Sibayan & Gonzalez, 1996; Manarpaac, 2008).

But “coloniality survives colonialism” (Maldonado-Torres, 2007, p. 243). As a political and economic system of domination which characterizes particular periods of history, colonialism may indeed be a thing of the past. However, it “is maintained alive in books, in the criteria for academic performance, in cultural patterns, in common sense, in the self-image of peoples, in aspirations of self, and so many other aspects of our modern experience” (p. 243). We refer to this condition as the coloniality of everyday life today. In the teaching of English, what is very much alive is a body of knowledge and network of practices which remain quintessentially colonial in nature (Moncada, 2007).

For example, the construct of the native speaker continues to mobilize the policies, practices and materials of many scholars and teachers today (Rubdy, 2015; Kiczkowiak & Lowe, 2021). Much has been written about the destructive impact of native-speakerism in the profession – the belief in the superiority of ‘native speakers’ in all aspects of teaching and learning (Holliday, 2006) – on the lives and identities of teachers and students whose first language is not American or British English. Just one case in point: many textbooks around the world “emphasize the image of the native speaker (man, white, heterosexual) in a superior relation or position to other interactants in dialogues” (Soto-Molina & Méndez, 2020, p. 13) which “consolidate[s] certain deficient practices, prejudices and stereotypes while at the same time strengthening or weakening local or national awareness”. Similarly, there have been calls to recognize the multilingual make up of English language classrooms, and thus a ‘multilingual ELT’ (Tupas & Renandya, 2020; Cummins, 2009), yet language teaching methods, beliefs and attitudes remain firmly monolingualist in nature. That is, there remains a deep-rooted predilection towards rejecting or devaluing the role of multilingual and multicultural resources in English language classrooms because they purportedly affect the learning of English negatively. Despite all the critical work of scholars (Kumaravadivelu, 2016), the English language classroom essentially remains a colonial space where English-Only ideologies and practices thrive.

In this paper, I focus on mapping ways of decolonizing language beliefs and ideologies in ELT. In doing so, however, I align myself with Kumaravadivelu’s (2016) contention that “Seldom in the annals of an academic discipline have so many people toiled so hard, for so long, and achieved so little in their avowed attempt at disrupting the insidious structure of inequality in their chosen profession” (p. 82). He also refers to continuing practices and ideologies in the English teaching profession which perpetuate monolingualism and native speakerism in all aspects of the profession, including hiring practices and the production of knowledge, despite intense and concerted intellectual elaboration on these harmful professional, teaching and learning orthodoxies. A decolonial option, Kumaravadivelu continues, “demands action” because “(w)ithout action, the discourse is reduced to banality” (p. 82). Thus, in this paper, I would like to share a particular action – a concrete, ‘ordinary’ project of decoloniality – which aims to highlight the centrality of engagement with deep-rooted language beliefs in teacher training. This is a Sociolinguistics in English Education (SEED) project, a certificate course for English language teachers and administrators which helps teachers earn Continuing Professional Development points for the renewal of their professional license. Such a seemingly ordinary or mundane project, if mobilized through a decolonial lens, allows us to link intellectual elaboration with different forms of structural inequities in the profession. In the end, a decolonizing approach to critiquing and transforming language beliefs and ideologies demands ‘action’ (e.g., the SEED project) which is embedded in intersecting structures of power in the profession. To put it another way, decolonizing language beliefs and ideologies in ELT does not simply involve reviewing, revising and overhauling curricula; it involves confronting systemic inequalities of knowledge production as well as unequal access to such transformative curricula in the first place. Elements of epistemic decolonization, knowledge activism and social justice are entangled in the conceptualization and implementation of a decolonizing ELT project. But first, let us examine how a decolonizing agenda in ELT has come about in the field.

CONCEPTUAL SHIFTS DUE TO GLOBALIZATION

The globalization and spread of English have resulted in its diversification. Several conceptual lenses have emerged to make sense of this sociolinguistic transformation of the language. ‘World English’ (Rajagopalan, 2004; Crystal, 2004) characterizes English as having taken on a linguistic and cultural character which consolidates the influences of people using the language from different parts of the world. ‘English as an International Language’ (Smith, 1976; McKay, 2002), on the other hand, conceptualizes English as a conduit through which the different cultures of its speakers flow. The language no longer carries the culture of its so-called native speakers, but the cultures of its culturally diverse speakers.

‘World Englishes’ (WE) (Llamson, 1969; Kachru, 1992) does not only assert that English is no longer singular but multiple, but also that these multiple Englishes are expressions of cultural identities and postcolonial liberation. More importantly perhaps, it has provided evidence of the systematic nature of national differences in the use of English, thus we have many Englishes such as Philippine English, Singapore English, Malaysian English, and so on. ‘English as a Lingua Franca’ (ELF) (Jenkins, 2007; Seidlhofer, 2008), on the other hand, argues that as a result of globalization, the language has served as a communication tool between speakers in global or cross-national settings whose first languages or mother tongues are different from each other. ‘Global Englishes’ (Galloway and Rose, 2015) covers the range of Englishes from nation-based (WE) to non-nation-based varieties (ELF). Thus, it “is an umbrella and a more inclusive term that encompasses recognized English varieties and ELF” (Fang & Ren, 2018, p. 385).

‘Translingual practices’ (Canagarajah, 2012) argues that realities on the ground surface linguistic practices of speakers which break down the so-called artificial boundaries between languages and language varieties. What the speakers have at their disposal are unified communicative repertoires through which they are able to establish intercultural and interpersonal interactions. What this means is that the English language is embedded in (and indistinguishable from) these communicative repertoires, thus we need to focus on the “pluricentricity of ongoing negotiated English” (Pennycook, 2008, p. 30.3, italics supplied). Lastly, ‘Unequal Englishes’ (UE) puts the spotlight on power and inequalities between speakers of Englishes, arguing that while English has diversified into different Englishes as a result of globalization, some remain more valued than others (Tupas, 2015; Salonga, 2015). Many speakers of English have been mocked and even discriminated against at home, in school and in the workplace, among many other contexts of use.

While these varying sociolinguistic lenses give us different angles from which to appraise the globalization and spread of English, we should emphasize that they are all grounded in the assumption that English has diversified and such diversification has systematic implications for the linguistic and cultural transformation of English. Thus, collectively these ways of apprehending the diversification of English have resulted in various attempts to reconceptualize the teaching of English. In my review of the literature on the impact of scholarly work on the Englishes of the world on the ELT profession (Tupas, 2018), I have found three key routes to such reconceptualization, and one of these routes – transforming language beliefs and ideologies – is what frames the decolonizing agenda of SEED.

THREE ROUTES TO RECONCEPTUALIZING ELT

The first route revolves around the question about ‘what English to teach’ (Bernardo & Madrunio, 2015; Schaetzel et al., 2010). If various international, national and sub-national iterations of English language use have been empirically found to be linguistically and culturally legitimate, with their own logics of use, what happens then to ‘Standard English’ as the ideal teaching and learning norm in the classroom? What is the role of localized Englishes in the teaching of ‘English’? Should we continue to aim for standardized norms and rules in the use of English, or should we replace them with the norms and rules of localized Englishes? Much has been written to track noteworthy attempts to respond to this question about what English to teach, but the reality of Unequal Englishes has made it difficult to transform ELT through this route because assessment practices, along with global institutions of testing and textbook production, have by and large remained committed to promoting ‘native speaker’ norms as the ideals of teaching and learning (Soto-Molina & Méndez, 2020).

The second route revolves around the question of ‘how to teach English’ (Tupas & Renandya, 2020; Cummins, 2009). The multilingual character of English is one of the key assumptions of work around this question, while another related one is the multilingual character of the users of English themselves. In other words, no matter what one’s political and ideological stance is towards the legitimacy of (a) pluralized English or Englishes, the fact remains that in most of the English classrooms around the world, the contexts and participants are multilingual and multicultural (Tupas & Renandya, 2020; Cummins, 2009). Colonial language teaching methods from audiolingual to communication language teaching have practically denied the positive contributions of multilingualism to effective teaching and learning (Kumaravadivelu, 2003). However, with the unrelenting push of some scholarly work towards embracing and mobilizing multilingualism in schools, pedagogies of English as an International Language have been envisioned, mobilized and examined through multilingual and multicultural lenses (Marlina and Giri, 2014; McKay, 2002). The use of mother tongues and ‘non-standard’ Englishes to teach ‘English’ has been explored and debated extensively (Wheeler, 2010; Sato, 1989). Contrastive or bidialectal strategies which, for example, encourage noticing or language awareness of structural differences between two Englishes or between English and the students’ mother tongue(s), have been proven effective in the teaching and learning of English in the classroom (Lu, 2022; Wheeler, 2010).