by Nadya Shaznay Patel

This semester I took on the opportunity to join the Open Networked Learning (ONL) course, organised by facilitators from Swedish universities and other IHL educators and professionals from around the world like, CDTL, NUS. ONL is an open fully online course that “offers participants opportunities to explore and gain experience from engaging in collaborative, open, online learning in order to understand the value, possibilities and challenges of using digital learning environments to support teaching and learning” (ONL, 2020). Last fortnight, as part of our discussions on online participation and digital literacies, my team and I shared our individual experiences teaching online. That discussion spurred an interest in me to reflect on how a supportive environment can be created to engage students in an online teaching and learning experience.

Many of us lament that the time simply passes by when we teach online. The hours are never enough to cover every instructional activity that we had planned. Somehow, the consensus we get is that as tutors we perform “better” in face-to-face lessons, compared to when we need to teach fully online. The lack of a physical presence in a tutorial room/lecture seems to be one of the main reasons for the disadvantage.

I reflected on my experiences this past year teaching online. I thoroughly enjoyed it! And from my students’ feedback and evaluation reports, they seemed to have enjoyed it very much too. I thought the following are some of the factors and reasons that contributed to this.

First, I started the semester not so much with expectations but rather assurances. I shared with my students that no matter what the learning outcomes for the course are, I am keen to know their personal aims and motivations for taking my course. And if they can share them with me, I’ll be happy to guide them to achieve them. I also emphasized the importance of them to communicate openly with me. If they needed me to recap a past task/lecture or if they needed me to re-order or move quickly with the tasks, they could always request for that. I do believe that respectful and supportive relationships are especially crucial when engaging students online (Pittaway, 2012). Thus, I also affirm my commitment to ensure that my students get the best out of their online experience with me and that I would do all I can to cater to their learning needs. This means that I am flexible and adaptable with the (ungraded) tasks: what needs to be completed and when they need to be completed. These can actually be done without compromising the learning outcomes. As I respect my students’ needs and aim to create a supportive learning experience for them, I quickly gain their trust and cooperation in journeying through the semester with me.

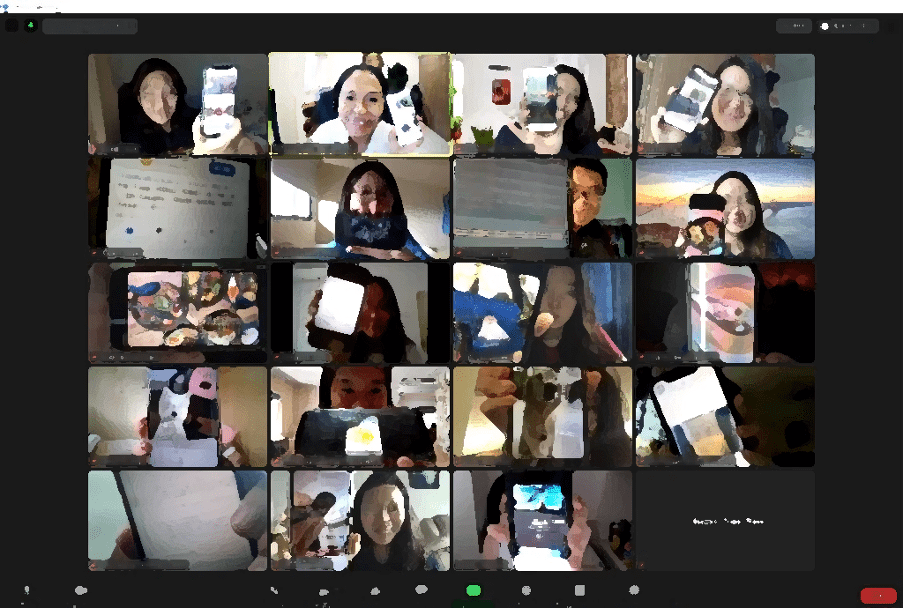

Check-in activity at the start of my online class. Screenshot by Nadya Patel.

Next, I would always project an authentic, real self of me to my students. This means that I have no virtual backgrounds, I do not hide what/who may be in my room/space as long as they are not disruptive/distracting to the online class. I thought that this will ensure that students themselves feel that they too can be their authentic/true self without fearing of being judged. This, consequently, allows my students to warm up to my lessons almost from the start and let their cameras stay switched on throughout the lesson. And as Pittaway (2012) proposes in her engagement framework, an engaged academic staff is a prerequisite for engaging students. Hence, I also project an enthusiastic and high-energy disposition while engaging students in my online class. It helps that I start every online session with a “check-in” (ice-breaker) activity! To respond to a prompt, students will each have 20 seconds to speak or share their screens. Examples of prompts include: (i) What’s your animal personality? Why?; (ii) What was your last photo/video in your mobile phone? Why?; (iii) What food are you craving for now? Why? Students commented that they do look forward to my online tutorials as they felt that they get the most of their time. Perhaps, these strategies allowed me to emphasise the importance of group relationships, interactions and even negotiations to establish rapport between my students and I (Kearsley & Shneiderman, 1999).

When engaging students online, I prioritise collaborative construction of knowledge and deepening of understanding than the actual completion of tutorial tasks. This is in line with the engagement theory by Kearsley and Shneiderman (1999), which has the fundamental premise that “that students must be meaningfully engaged in learning activities through interaction with others and worthwhile tasks” (p. 1). This means that I engage students in a dialogic scaffolding experience of the concepts and materials. They will have many opportunities to engage in high-level interaction with myself or with their peers in groups. I provide opportunities for students to catch up with their e-learning (asynchronous) tasks/reading by designing bite-sized instructional activities that require students to apply the concepts during the online tutorials. Through these, I aim to provide just-in-time instruction and scaffolding so that students’ misconceptions are cleared and understanding deepened.

When engaging students online, I prioritise collaborative construction of knowledge and deepening of understanding

Finally, I welcome out-of-class zoom consultations with students separately – in a prearranged day/time of their choosing. My main aim is to show my students that I will make myself available and accessible to them at any (reasonable) time they need me. This allowed students to trust my support and value the additional scaffolding they get. I found that in an online teaching environment, I should not be expecting students to progress in the exact same time as everyone else. Differentiated instruction does take a whole new meaning in teaching online. Thus, by designing tasks to allow students to work collaboratively at first in groups both during online tutorials and out of tutorials, I am able to get students to ultimately complete tasks independently once they have gained the competence to do so. Moreover, this increases the students’ motivation to want to give their best for the course since I am doing all I can to support them.

All in all, I feel that the physical presence that is lost in teaching online can very well be replaced with a deliberate and meaningful online presence! I would say that a consideration of the 3Vs are crucial for me to provide a supportive environment as I engage my students online. They are (i) Verbal: the dialogic interactions between myself and students and among students themselves matter; (ii) Vocal: letting my voice be free, varying my use of vocal for higher engagement; (iii) Visual: the multimodal visual aids that I use to complement my instruction and how I carry myself as their enthusiastic, positive and even smiling tutor.

References

Kearsley, G., & Shneiderman, B. (1999). Engagement theory: A framework for technology-based teaching and learning.

Pittaway, S. M. (2012). Student and staff engagement: Developing an engagement framework in a faculty of education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37, 37–45.