Assoc. Prof. Eleanor Wong, Director of the Legal Skills Programme at the NUS Law School shares how she used Google Docs to aid in improving her students' writing.

...continue reading

Assoc. Prof. Eleanor Wong, Director of the Legal Skills Programme at the NUS Law School shares how she used Google Docs to aid in improving her students' writing.

...continue reading

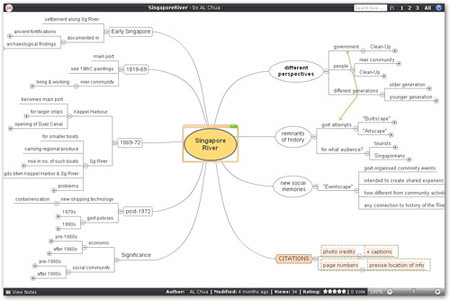

The mindmap starts off bare – just the main topic in the centre with the sub-topics surrounding it. As the tutorial progresses, the mindmap takes shape, like a creature sprouting colourful appendages. The end result is a visual summary of the lesson, which students find so useful that they take photos of it with their cameras.

Dr Chua Ai Lin is a mindmapping maven. The Department of History lecturer has been creating mindmaps since her days as an undergraduate. Initially, she used it for note taking, but she extended it to teaching and brainstorming when she progressed on to doing her Masters and PhD.

“I’ve never taught a single tutorial without using a mindmap,” Dr Chua highlights, “It’s an absolutely crucial and integral part of the way I teach.”

Her foray into mindmapping began when a cousin, who was teaching at NUS, introduced her to mindmapping, recommending the seminal book by Tony Buzan. Dr Chua, waiting to start her undergraduate studies at the time, didn’t need further encouragement to proceed. She read the book and put what she read into practice.

What was it that drew her in? She explains, “Ultimately, linear notes are not so fun to make. And it’s not just the colours but the way in which every time you make a mindmap, it’s very organic. It looks distinctive. At the end of the day you can enjoy is visually as well. I like that.”

During tutorials, Dr Chua splits the class into groups and asks them to discuss various sub-topics related to the lesson of the week. Each group has a different topic. As the students present what they have discussed, she draws the mindmap on the whiteboard. So, in a sense, it is the students who come up with the mindmap.

“Mindmaps are very good at drawing together what everybody in the class is saying and making links between what they are all saying so that we can see how it is all tied together,” Dr Chua points out, "The organic look of multicoloured hand-drawn mindmaps helps to stimulate right brain/creative thinking as well as being a visual mnemonic device"

Pen-and-paper or marker-and-whiteboard mindmaps do have their limitations, as Dr Chua observes, “There are times when you want to do something presentable, to make handouts, for example. Also, I wanted to find a way to use mindmaps for lectures as I feel the linear form of Powerpoint presentations is boring.”

She actively researched mindmapping software, narrowing down her choices to a few which she downloaded and tried. While she is partial to iMindMap – Tony Buzan’s official mindmapping software – for its highly organic-looking mindmaps, Dr Chua used an free online mindmapping tool called Mindomo to create a mindmap, about the Singapore River, for distribution to her class. All Dr Chua needed to do to share the mindmap was to inform her students of the URL.

Dr Chua offers one other use, “With mindmaps online, students can possibly collaborate on a mindmap, though I haven’t tried that.”

Will Dr Chua give up pen-and-paper mindmaps? “For myself, I would still draw them on paper because of that creative and organic look,” she states, “But there are times when you want to use software to do it.”

CIT has launched an online mindmapping tool for staff and student use. More information can be found in this issue of IDEAS and on the information page about the Mindomo-powered online mindmapping software.

eLearning Week (eLW) posed two big questions to all lecturers involved in the exercise: how to delivery lectures and how to conduct tutorials? While most of her colleagues chose to use Breeze to deliver their lectures, Ms Mary Lee, an Instructor at the Communications & New Media Programme, opted for a less conventional method – an audio podcast.

“I think it’s an expedient way of delivering a lecture, as well as my desire to explore the audio medium” Mary explained, “It’s quite creative. I actually had in mind executing a radio talk show format. I thought a podcast was a great opportunity.”

Other reasons included her colleagues’ difficulties with Breeze and Centra – the more oft used methods of delivering lectures during eLW as well as her fear of technical glitches.

With the format decided, Mary proceeded to flesh out the podcast. She would be covering press releases and news conferences in the podcast lecture for NM3219 Writing for Communication Management.

“I was thinking, ‘What are the resources on campus that I can use? Who can be my sparring partner, my talk show host?’ And I looked around and I thought, ‘Hey, there’s Radio Pulze!’ They may be students but they are students who are very serious about wanting to do radio broadcasting as a career. I thought maybe I could sound them out about my proposal and maybe they’d be keen to take this on. You know, it’s something different and yet educational. True enough, they were very enthusiastic!” Mary shared.

With students from Radio Pulze on board, she set out to script the programme, as she wanted to make sure that the podcast covered her learning points and objectives.

“I enjoyed the process a lot more,” she said of writing the script, “I did not have to do PowerPoint! I think better in Word, because PowerPoint is linear and Word, I can just move [things] around. It was like writing an essay first and then polishing it so that it’s more of a spoken thing, a conversational thing – a dialogue.”

Karthik Srinivasan, a 3rd year Engineering student from Radio Pulze, was Mary’s co-host for the podcast. After an initial meeting, they recorded the podcast in about two hours at CIT’s studio. Melvyck Leong, another student from Radio Pulze, helped with the post-production, working throughout a weekend to polish the podcast.

CIT staff Lilian Lim then helped to publish the podcast and the transcript in IVLE. She helped to coordinate the production, planning the timeline, handling logistics and coordinating with the students from Radio Pulze. Through Lilian’s efforts, the podcast was delivered before the deadline.

Mary exclaims, “She made everything plain sailing for me! Lilian worked out the production schedule and included buffer time, if it wasn’t perfect and I wanted to re-record. She made sure things ran properly.”

Students from NM3219 seem to have taken the podcast lecture in their stride, with no complaints about the lecture. On Mary’s part, she found the whole experience enjoyable – from conceptualizing and writing the script to recording the podcast with the enthusiastic Radio Pulze students.

1. How did you get to know about the Classroom Response System?

CIT invited the representatives in Singapore to conduct demonstrations on their product, and I attended these sessions.

2. Why did you decide to try it out?

I had tried the quiz system on IVLE, and wanted an alternative system that allowed me to conduct the quizzes during class.

3. Which class did you use it for?

I used the Classroom Response System for my GEK1049 module during the special term.

4. What was its impact in the classroom?

This is hard to gauge. The feedback responses were blended with more general impressions of my teaching. So, it is hard to separate these from students’ more direct responses to the use of CRS. After all, the use of any mechanism for teaching is usually built on one’s ideas and principles of teaching, and students in their own way, are able to see at least some of these as they are practically enacted in the classroom.

5. What are the benefits and drawbacks of the system?

A benefit of the system is the quiz facility itself, which is its prime selling point. Of course, quiz questions could be asked by using traditional means, but the students’ answers and the lecturer’s feedback cannot be given quickly enough. Whether to have the quiz at all, of course, depends on the nature of the module that one teaches, and the method of teaching that one adopts for the module. So this is not something that could be used for all modules.

One drawback is the logistics involved. For a class of 40+ students, one has to carry two bags of handsets or ‘clickers’. These bags are supplemented by the bag containing the notebook computer. So the lecturer has to carry three bags for a class of moderate size.

The reason for bringing along the notebook is that I have found that it is best to separate the PowerPoint slides on the seminar room computer, from the display for the system on the notebook. Also, even if one wants to have both on the same computer, the notebook serves the function of ensuring that the information that is registered by the software is registered on the lecturer’s own personal computer, and not on a computer that is also used by other people. A further reason for bringing along the personal notebook is that, although one can install the software on the seminar room computer, one doesn’t know how stable it would be.

The initial preparation was time consuming. There is a learning curve for learning the software – it is not something that one knows how to use immediately. Also, one must try to integrate the quiz questions into one’s lectures in order to make the use of the system worthwhile.

6. Would you use it again? Why or why not?

I am thinking of using the Classroom Response System again. I will however be hesitant to use it for big classes – imagine carrying several bags to the lecture theatre, and of course, one can’t do it alone if there are too many to carry! Moreover, the logistics of distributing the handsets to students at the beginning of the session, and collecting them at the end, is a hassle if the class is too big, and the process may of course eat too much into one’s lecture time. Classes which depend on evaluative responses are also a problem, especially with a system like the CRS, that allows only one correct answer for each question, or does not allow answers with variable points weightage.

---------

For further reading, you might want to borrow Audience response systems in higher education : applications and cases edited by David A. Banks (LB2395.7 Aud 2006) from the NUS Central Library.