A number of scholars have characterised the Zhuangzi’s epistemology as anti-rationalist, anti-intellectual, or sceptical of conceptual knowledge (knowledge-that). I suggest that this characterisation of its epistemology is unhelpful and wrongheaded for two primary reasons. First, it glosses over a key similarity between the Zhuangzi’s approach to the acquisition of skills, and that of Confucian self-cultivation. Both traditions share the view that discipline, which may include knowledge-that, is crucial to cultivation. Secondly, to characterise the Zhuangzi’s epistemology as ‘intuitive know-how’ is a reductionist move that overlooks the multi-faceted nature of the cultivation of skills in the text.

Philosophy Seminar Series.

Date: Thursday, 8 Nov 2012

Time: 2pm – 4pm

Venue: Philosophy Resource Room (AS3 #05-23)

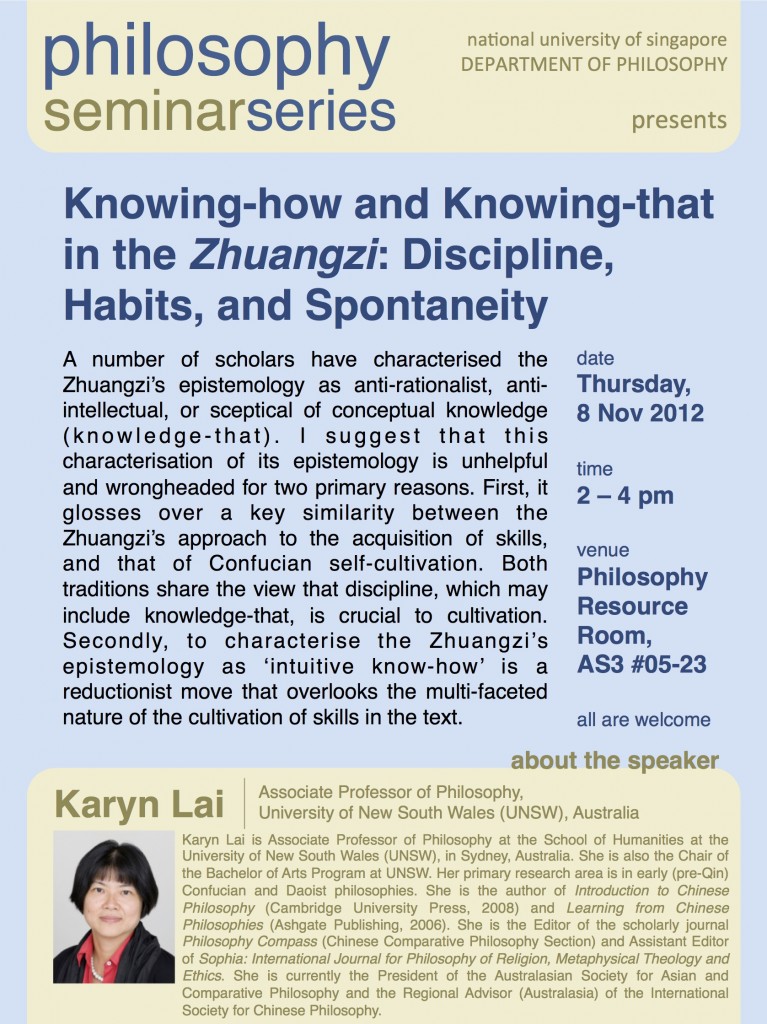

Speaker: Karyn Lai, Associate Professor of Philosophy,

University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia

Moderator: Dr. Neil Sinhababu

About the Speaker:

Karyn Lai is Associate Professor of Philosophy at the School of Humanities at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), in Sydney, Australia. She is the Chair of the Bachelor of Arts (BA) Program in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at UNSW. Her primary research area is in early (pre-Qin) Confucian and Daoist philosophies. She is the author of Introduction to Chinese Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 2008) and Learning from Chinese Philosophies (Ashgate Publishing, 2006); and of numerous articles in peer-reviewed journals. She is the Editor of the scholarly journal Philosophy Compass (Chinese Comparative Philosophy Section) and Assistant Editor of Sophia: International Journal for Philosophy of Religion, Metaphysical Theology and Ethics. She is currently the President of the Australasian Society for Asian and Comparative Philosophy and the Regional Advisor (Australasia) of the International Society for Chinese Philosophy.

Karyn Lai is Associate Professor of Philosophy at the School of Humanities at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), in Sydney, Australia. She is the Chair of the Bachelor of Arts (BA) Program in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at UNSW. Her primary research area is in early (pre-Qin) Confucian and Daoist philosophies. She is the author of Introduction to Chinese Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 2008) and Learning from Chinese Philosophies (Ashgate Publishing, 2006); and of numerous articles in peer-reviewed journals. She is the Editor of the scholarly journal Philosophy Compass (Chinese Comparative Philosophy Section) and Assistant Editor of Sophia: International Journal for Philosophy of Religion, Metaphysical Theology and Ethics. She is currently the President of the Australasian Society for Asian and Comparative Philosophy and the Regional Advisor (Australasia) of the International Society for Chinese Philosophy.

Her current research focuses on epistemology in Chinese philosophy. The research begins by asking what it is to know in some of the pre-Qin texts. For a start, these texts are not fundamentally concerned with propositional knowledge, or what epistemologists call knowing-that. They are interested in ways of knowing that are action-guiding or that have practical outcomes. Here, epistemological concerns and their associated approaches to learning reflect the belief that contextual details are irreducible in our understanding of action, a person’s character, and his or her ultimate commitments. Lai proposes that the primary concern in pre-Qin Chinese philosophy is not primarily with knowledge-that, nor even with knowing-how (for instance, how to conduct oneself at a funeral), but with knowing-to, a capacity to act in the moment (e.g. to be tactful in a particular situation while blunt in another). The aim is to articulate an account of knowing that highlights epistemology in light of the agent in action that has to date not been explored either in western analytic epistemology or Chinese philosophy.