Hello everyone,

Some days ago, we shared a sneak peek about one of the many upcoming projects on our social media platforms. This blog article is a follow-up to those posts. NUS Libraries is collaborating with the NUS School of Computing (SoC) to establish a Computing Gallery which will be in COM 1 (Computing 1, SoC). Slated to open in Q2 of 2023, the launch of the Computing Gallery will be very timely since the NUS School of Computing will be celebrating its 25th Anniversary. Given the School has evolved significantly since its inception, this project is a great way to mark its achievement.

While working on the research for this project, the team discovered a lot of interesting content from our rich collection. One of the topics that caught my eye is the role of women in the computing industry. In the course of researching this topic, I discovered several great reads mostly from our collection. I have listed the titles at the end of my article if you are interested to learn more about them. In a journal article titled, Recognizing a Collective Inheritance Through the History of Women in Computing, author Erika E. Smith stated that the definition of the word “computer” has evolved due to the ever-changing nature of digital technology.

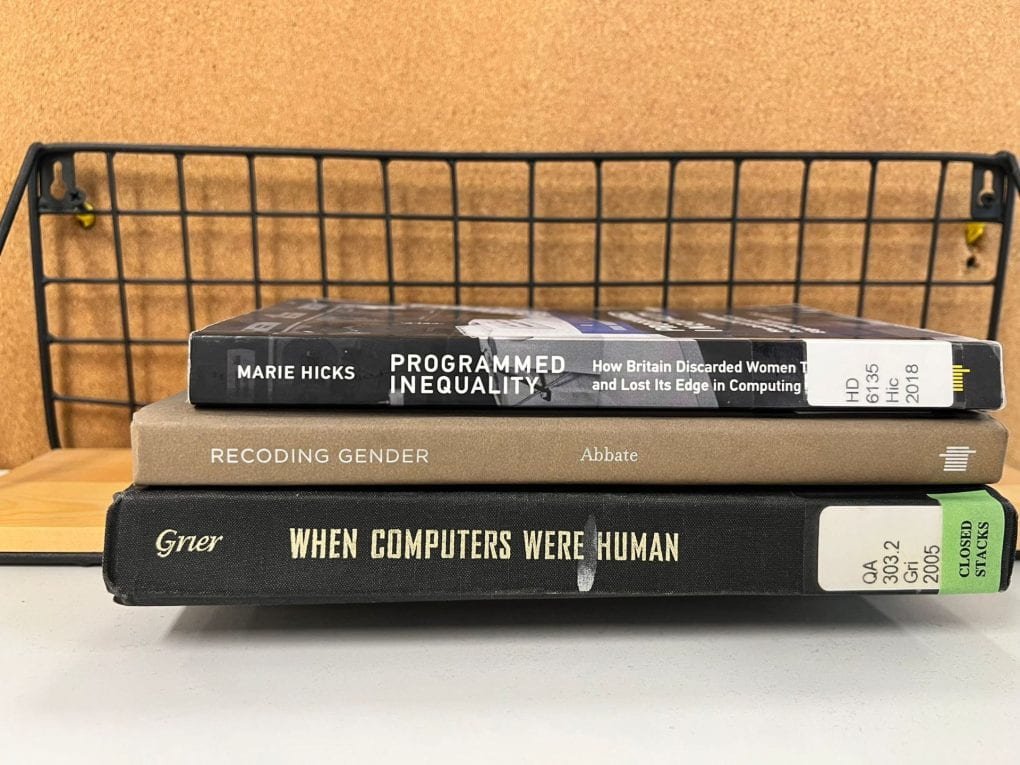

Snapshot of some books that can be found on the subject in our Collection

So did the role of women as they were instrumental in the development of the industry from, “Hardware” to “Software”. They were the pioneer simulators, assemblers, and programmers of the digital machines we know today. Unfortunately, women have been plagued by one of the biggest problems in the industry. In The Impact of Women in Computer Science History: A Post-War American History, Karina Mochetti, an Assistant Professor at the University of British Columbia stated that women’s achievements have been regarded skeptically, and highlighting their role becomes an issue despite the countless contributions they made.

In the early 19th century, scientists and governments were collecting reams of data that needed to be processed, particularly in astronomy, navigation, and surveying. These jobs required precision, the ability to work for long hours and were traditionally held by men. However, by the end of the century, many companies recognised that hiring women in the industry could significantly cut costs. Steady growth in the middle class enabled a generation of young women to be educated and trained in math. David Alan Grier, author of When Computers Were Human noted that many companies started hiring all women teams since they could be paid much lesser than men.

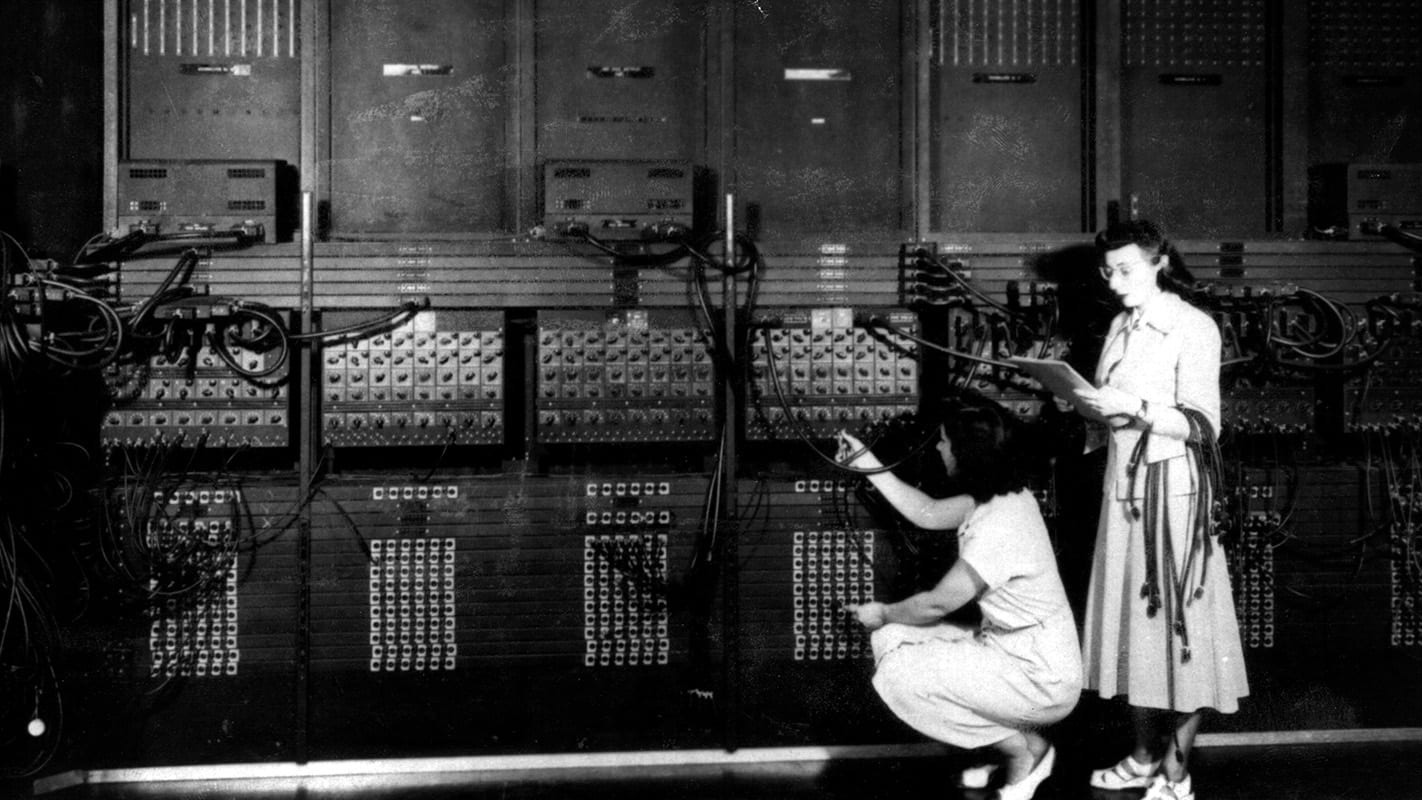

Mochetti and other authors observed that as early as World War I, women were hired to calculate artillery trajectories, support engineers, and so forth while the men were out fighting. They used to be sitting at tables and working on math laboriously. According to Marie Hicks, a historian and author of Programmed Inequality: How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost its Edge in Computing, men with elite education generally wanted no part in such work as they were viewed as dull, rote, and of low status. Many of the calculations were in fact, pretty complex and required advanced math skills.

Perhaps one of the most well-known women in computing is Augusta Ada King (Countess of Lovelace), a remarkable figure in the Victorian era. She published a paper at the age of 27 in 1843 which formed part of the appendix for an article, Sketch of the Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage. The paper provided an account of the principles of the machine and a table displaying how it could compute the Bernoulli numbers described as the world’s first computer programme. Therefore, it comes as no surprise when she is commonly referred to as the world’s first computer programmer. In Recognizing a Collective Inheritance through the History of Women in Computing, Smith shared that, Lovelace’s work and name were largely forgotten despite groundbreaking projects such as the ENIAC.

Ada Lovelace painted in the 1830s by Margaret Sarah Carpenter

We saw an increase in the demand for computation during World War II. In his book, Grier noted that more than “half” of the computers were women. Unfortunately, many knew that they would get married and these jobs would not land them a career in computing. In 1944, Astronomer L.J. Comrie expressed that “female computers” were only of use till they got married and became experts in managing household accounts in a Mathematical Gazette article, “Careers for Girl”. As such, their formal designations or paychecks were typically unworthy of the work produced or their skill set.

For example, in Programmed Inequality, Hicks observed that the majority of the women working for the Civil Service in the United Kingdom were not paid equally to the men in 1955. The government had an approved rate for certain jobs in which men and women were employed for the same categories. The pay scale for men in these positions was equivalent to market rates. Therefore, the government was forced to raise the women’s pay to that of the men for the positions whereby men were the majority or formed a large percentage employed to avoid a backlash. Given numerous jobs had been segregated by gender or feminized for decades, only a handful of women had the same designation as men.

Did you know that women were commonly known as “human computers,” a term used to refer to those who performed computing and calculating related activities? One of the first things that come to mind when I think of the term “human computers” is a movie titled Hidden Figures based on a book by Margot Lee Shetterly. Released in 2016, the movie is a true story about three African American math teachers from the South’s segregated public schools. The women were called to solve mathematical equations for NASA in the early 1960s due to the labor shortages of World War II. The female mathematicians dealt with sexism and racial inequality while playing an integral role in the successful launch of astronaut John Glenn into orbit.

Several authors including Hicks and Abbate highlighted the decline of “human computers” and the rise of early digital computing from the 1950s to 1970s. The jobs no longer required humans to execute the functions of the machines but rather programme the functions that need to be executed. During this period, industry practitioners complained about the lack of trained professionals. This came as no surprise as gender discrimination against women resulted in their lack of employment opportunities as skilled programmers, according to Abbate.

She then stated that the United States newspapers listed job advertisements under separate headings for “Help Wanted-Male” or “Help Wanted-Female”. While in the United Kingdom, newspapers distinguished between “Appointments” and “Women’s Appointments” till the mid-1970s. Due to technological advancements, programming was made simpler so any person with no computing experience would be able to operate the necessary equipment with a few hours of instruction. In Programmed Inequality, Hicks observed that Western Europe alone invested £250 million in computers in 1965. This was a very clear indication of what the future of labour would look like.

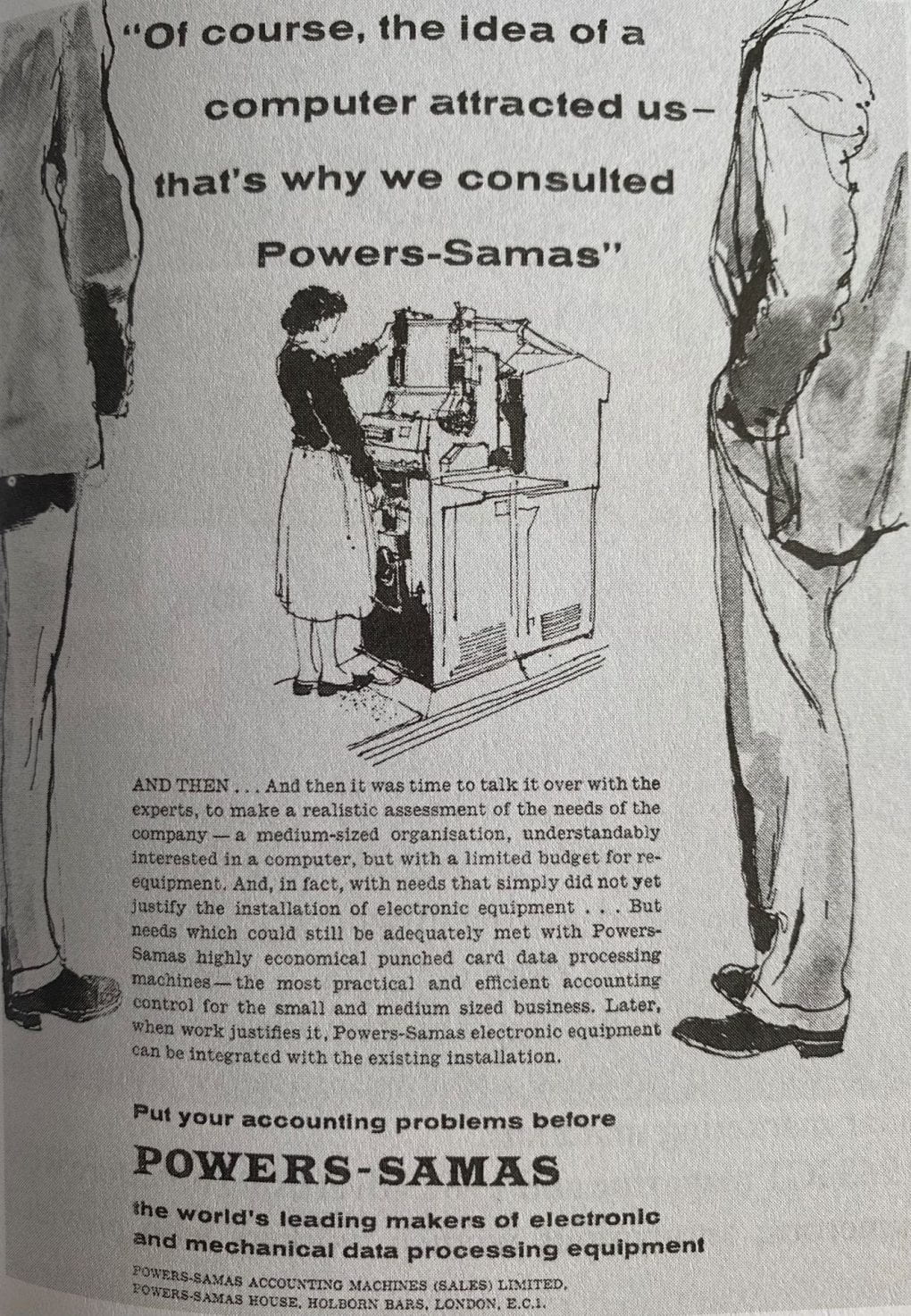

Given most managerial positions were held by men who made the call on acquiring computing equipment, marketers started highlighting workers’ gender as a selling point. Hicks pointed out that nearly all the photographs selling or showcasing computers featured a rather plain-looking and conservatively dressed female standing or sitting while working at machines. The industry saw subtle changes in advertising style with machines becoming more sophisticated. Initially, the women only presented their backs to the viewer, they did not even have a face. Over time, they became the subject itself.

Power-Samas advert in Office Magazine, May 1958

The “Susie” advert which appeared in the Office Methods and Machine Magazine in 1967

Mochetti, Goyal, and Smith observed that there was a severe under-representation of women despite a few holding positions of power and responsibility in jobs created by new digital information technologies over time. In a journal article titled, Women in Computing: Historical Roles, the Perpetual Glass Ceiling, and Current Opportunities, Amita Goyal argued that there has been a “perpetual glass ceiling” for women working in this area. She then demonstrated how there were still low numbers of women in computing science, and the arbitrary salary gap between men and women was cause for concern. Similarly, a Vanity Fair article by Emily Chang in 2018 offers insight into a culture is that highly hostile to women.

Several authors including Goyal and Smith stressed that this “glass ceiling” still exists today and women still complain about harassment and having their work belittled. Many times, women started their careers with happiness or even excitement which eventually dwindled over time. Thomas J. Misa, author of Gender Codes: Why women Are Leaving Computing noted that women just made up 29% of the white-collar computing workforce in the United States, in 2005. That’s a good 10% down from the 1980s. She discussed a Harvard Business School report which concluded that many women work in the industry for around 10 years after which about half of them leave the workforce. Why would these women do that, after all, they chose the profession for themselves? According to Misa, the dropout was a result of being “pushed and shoved by macho work environments, serious isolation, and extreme job pressures”.

Over the last few days, there has been a lot to unpack from all the research. Upon reflection, it makes me wonder if women in Singapore have faced similar challenges in the computing industry. Over the years, we have been observing more women-in-tech initiatives and opportunities in Singapore. They are hard to miss given the huge budgets and massive marketing campaigns. However, these do not offer us any insight into the challenges that exist. In my next blog article, I will be looking at our little red dot as a case study.

Cheers,

Poonam

Bibliography

Abbate, Janet. Recoding Gender: Women’s Changing Participation in Computing. History of Computing. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2012.

Emily, Chang. ‘“Oh My God, This Is So F— Up”: Inside Silicon Valley’s Secretive, Orgiastic Dark Side’. Vanity Fair. Condé Nast, February 2018. https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2018/01/brotopia-silicon-valley-secretive-orgiastic-inner-sanctum.

Evans, Claire Lisa. Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet. New York, New York: Portfolio/ Penguin, 2018.

Goyal, A. ‘Women in Computing: Historical Roles, the Perpetual Glass Ceiling, and Current Opportunities’. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 18, no. 3 (Fall 1996): 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1109/85.511942.

Grier, David Alan. When Computers Were Human. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Hicks, Mar. Programmed Inequality: How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Its Edge in Computing. History of Computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017.

Hollings, Christopher, Ursula Martin, and Adrian C. Rice. Ada Lovelace: The Making of a Computer Scientist. Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2018.

Misa, Thomas J., ed. Gender Codes: Why Women Are Leaving Computing. Hoboken, N.J. : [Piscataway, NJ]: Wiley ; IEEE Computer Society, 2010.

Mochetti, Karina. ‘The Impact of Women in Computer Science History: A Post-War American History’. Transversal: International Journal for the Historiography of Science, no. 6 (30 June 2019). https://doi.org/10.24117/2526-2270.2019.i6.07.

Payette, Sandra D. ‘Culture Not Numbers: Dilemmas and Discourses of the Underrepresentation of Women in Computing.’ Order No. 10846885, Cornell University, 2018. http://libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/dissertations-theses/culture-not-numbers-dilemmas-discourses/docview/2108516183/se-2.

Shetterly, Margot Lee. Hidden Figures: The Untold Story of the African American Women Who Helped Win the Space Race. London: William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2017.

Smith, Erika E. ‘Recognizing a Collective Inheritance through the History of Women in Computing’. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 15, no. 1 (1 March 2013). https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1972.