Technology in Pedagogy, No. 20, April 2014

Written by Kiruthika Ragupathi

Introduction

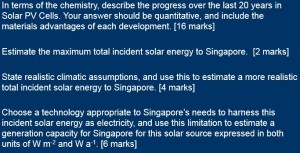

What is scaffolding? How does it help learning? Can technology be used? Does it work? And who is Vygotsky? These were the questions that Adrian Lee, a senior lecturer in the Department of Chemistry at the National University of Singapore set out to answer in this session on “Virtually Vygotsky: Using Technology to Scaffold Student Learning”. Through this session, Adrian showcased technologies that can be used before, during and after class to provide appropriate scaffolding to students.

Scaffolding, he says, can come in a variety of forms, from increasing engagement, providing alternate learning strategies, resolving learning bottlenecks, and (paradoxically) taking away support to allow students to master material, among other things. The Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) underpins some of the ideas of constructivism, and according to Vygotsky (1978), “the actual developmental level characterizes mental development retrospectively, while the Zone of Proximal Development characterizes mental development prospectively.” Vygotsky believed that when a student is at the ZPD for a particular task, providing the appropriate guidance (scaffolding) will give the student enough of a “boost” to achieve the task.

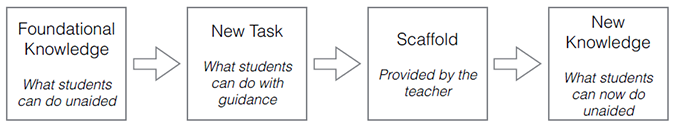

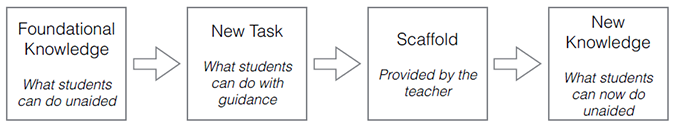

The term ‘scaffolding’, coined by Bruner, was developed as a metaphor to describe the type of assistance offered by a teacher or more competent peer to support learning. In the process of scaffolding, the teacher helps student master a task or concept that the student is initially unable to grasp independently. The teacher then offers assistance with only those skills that are beyond student’s capability. Once the student masters the task with the benefit of scaffolding, the scaffolding can then be removed and the student will then be able to complete the task again on his own. Therefore, what is of great importance is enabling the student to complete as much of the task as possible, unassisted (Wood et al, 1976). How this translates to the constructivist approach is that the area of guidance grows as we teach the subject matter, and as the students mastery level of the subject concepts changes. The model of instructional scaffolding can be illustrated as below:

Adrian also emphasized on the seven principles of undergraduate education by Chickering and Gamson (1987) that is still incredibly pertinent in today’s teaching.

- Encourages contacts between faculty and students

- Develops reciprocity and cooperation among students

- Uses active learning techniques

- Gives prompt feedback

- Emphasizes time on task

- Communicates high expectations

- Respects diverse talents and ways of learning

It is these principles, he said, that shapes his teaching and helps him decide on when and how to provide the much needed scaffolding for his students’ learning.

Note:

For more information on how to use IVLE to implement the 7 principles of effective teaching, please see: http://www.cdtl.nus.edu.sg/staff/guides/ivle-tip-sheet-2.pdf

Scaffolding student learning through technology

Adrian illustrated some technologies that he uses to scaffold student learning, some of which he highlighted were available within IVLE. The first five items are those that are used outside the classroom while the last item is a technology that is used inside the classroom.

1. Lesson plan

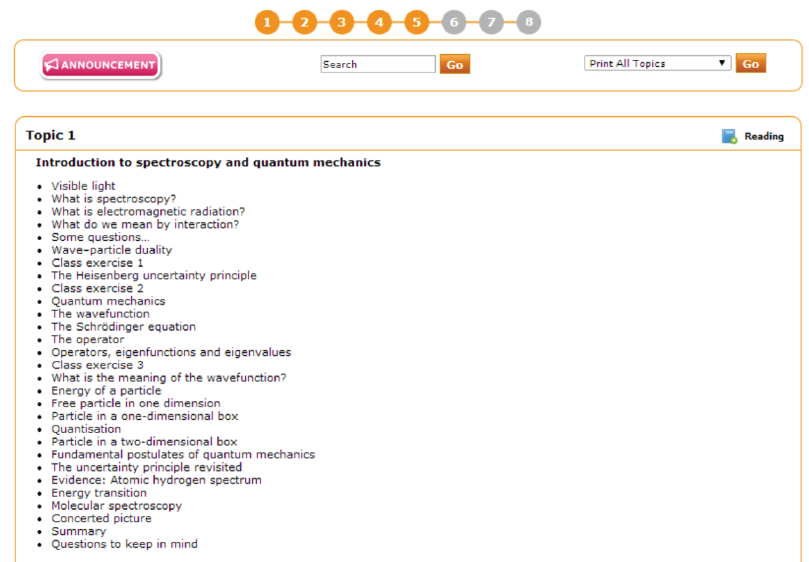

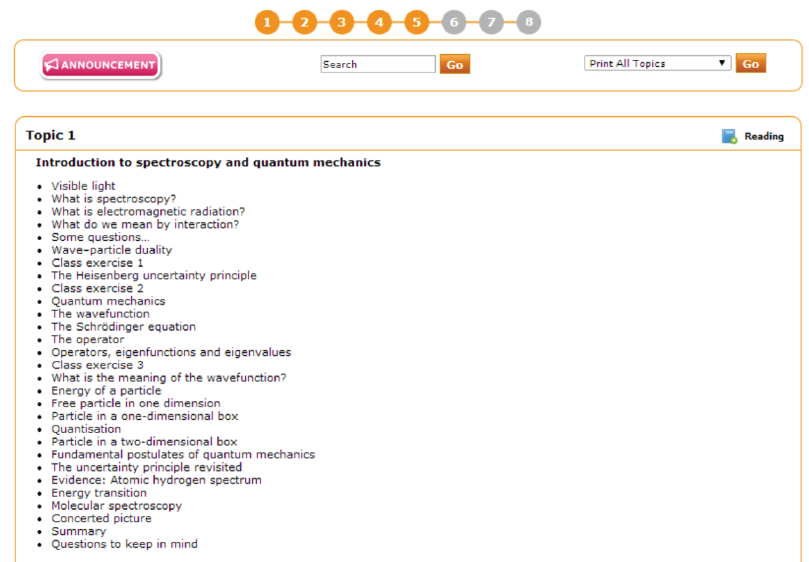

He explained that he uses IVLE lesson plan to connect all the instructional resources for the module, and as a one-stop location for students to access these resources. He uses the topic approach compared to the commonly adopted weekly approach, as the topic approach can easily act as an index of his lecture notes and remains accurate on a year-to-year basis as it is independent of changing national holidays.

Five to six different concepts are covered each week. Each topic in the lesson plan usually consists of:

- Play-lists – to allow students to access the online lectures in the recommended sequence before the face-to-face lessons

- Weblinks – to provide additional materials, wherever necessary, to enhance student understanding

- Online quizzes – to test student understanding of concepts. Each quiz consists of about 10 MCQ or “fill-in-the-blank” questions

- Multimedia tutorials – to support the various class exercises through tutorials that discuss the concepts

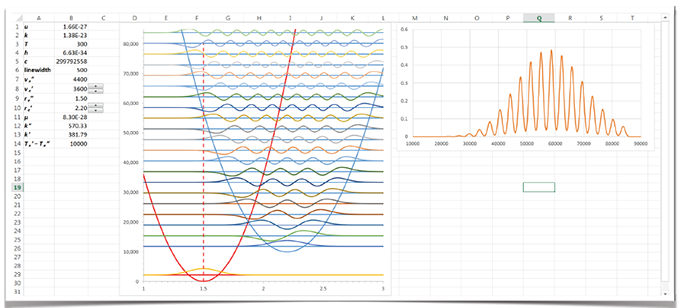

- Spreadsheets – to enable students to work out problems, thereby boosting understanding through interactive visualizations

A sample lesson plan for one topic is shown below:

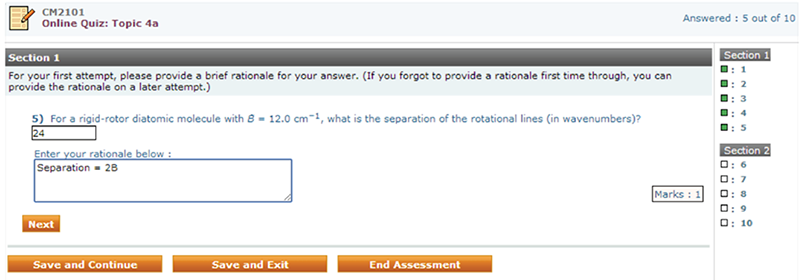

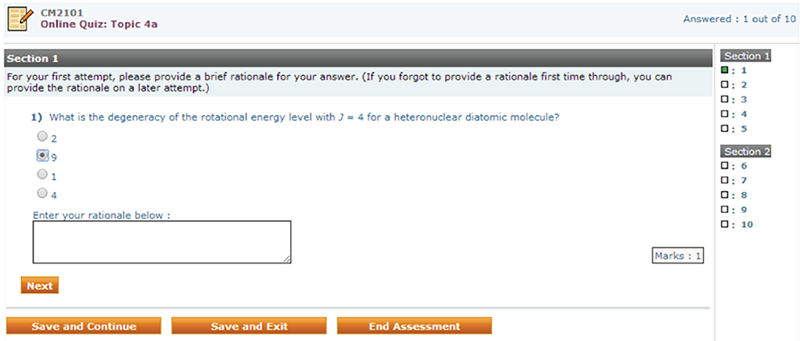

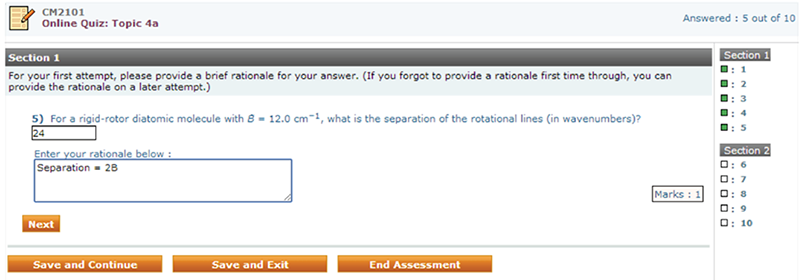

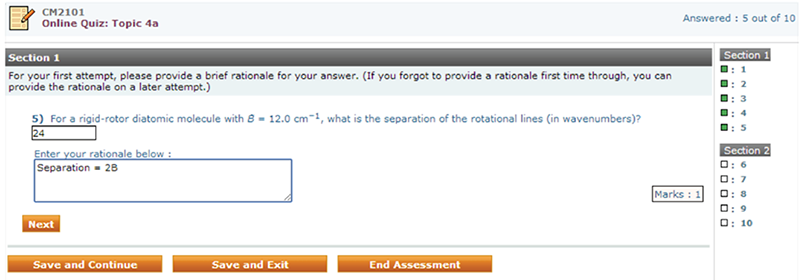

2. Online quizzes

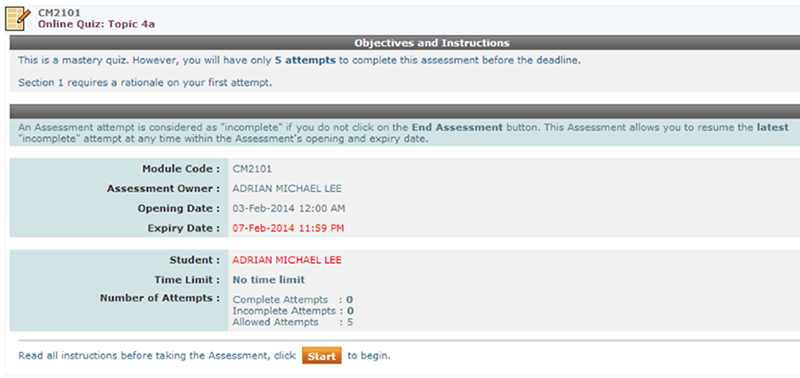

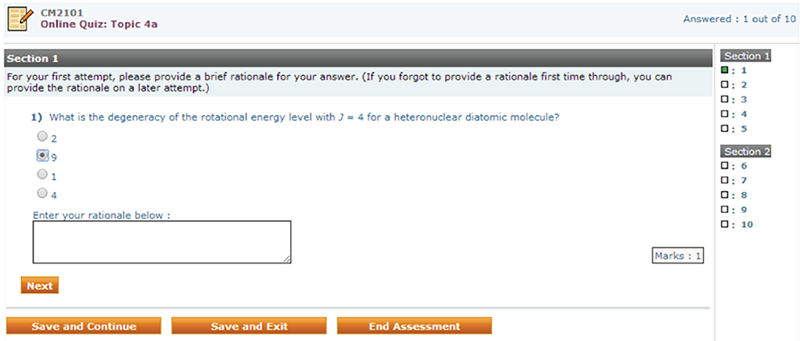

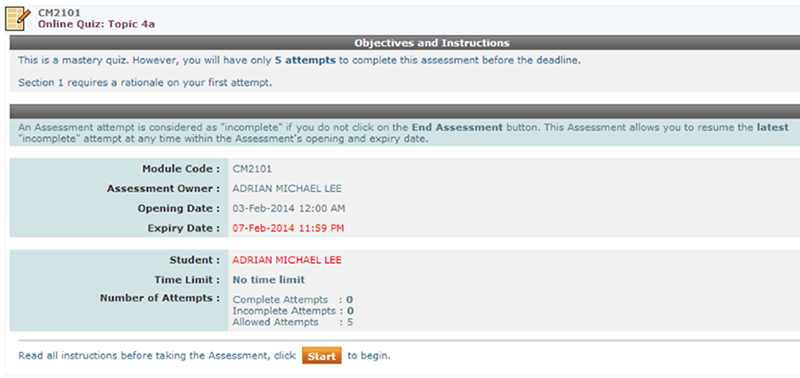

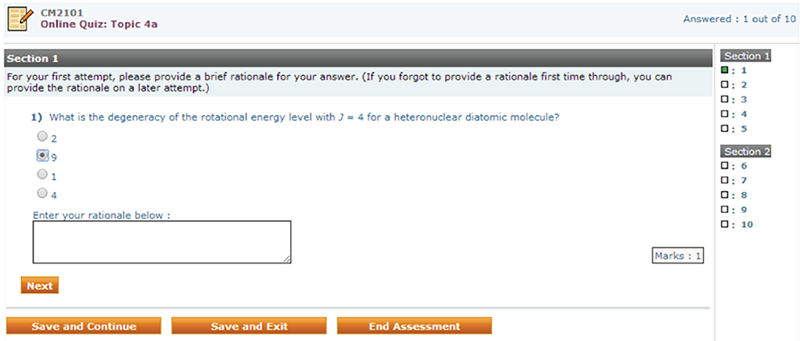

Online quizzes are mainly used to understand what students don’t know. Students watch lecture videos before class (a flipped classroom approach), and take a short quiz on the lecture content. Each quiz question is designed as an MCQ type or “fill-in-the-blank” type, but it also requires students to provide a rationale for their chosen answer. Each student is given 5 attempts. When a student gets a question wrong, feedback is provided along with a hint pointing to the right answer. Students generally would be able to get full marks for the online quizzes within the allowed 5 attempts. The rationale students provide for each MCQ question will give insights on what students don’t know. Adrian explained that his focus was mainly on students’ first attempt of the quiz, as this can act as a good gauge of students’ understanding. He said he used this information to fine-tune his lectures, to pick out discriminatory questions and address student misconceptions.

Samples of the online quiz, designed using IVLE assessment tool is illustrated below:

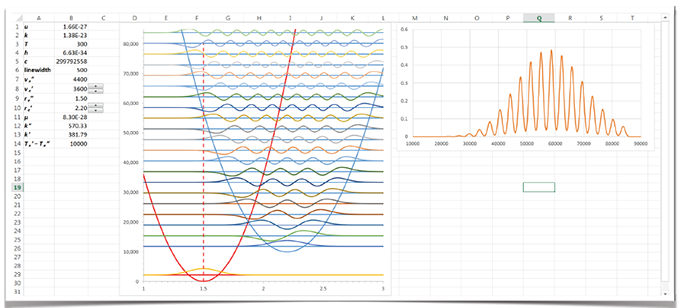

3. Interactive visualizations

Adrian uses excel spreadsheets to design interactive visualizations. For each question appearing on the online quiz (discussed above), he provides students with at least one related interactive visualization. Students will be allowed to interact with these visualizations while attempting the online quizzes. They will be able to visualize changes that occur when changing the values provided in the spreadsheets.

4. Peer assessment

Peer assessment is an important component that can be used to enhance student learning. Adrian uses peer assessment to get students to assess their peers’ essays. He also provides a grading rubric that students can use as a guide while marking. Finally, he makes it a point to return the feedback from the peers back to the individual students. Each student gets to mark at least 3 essays. This allows students to see other’s work compared to their own essays. His class, being a heterogonous class prompted him to moderate student grades taking into account the easy-graders and strict-graders. In addition, he also gets students to mark their own essay after having marked their peers’ essays. This acts as a reflective element for their own learning.

Thus with peer assessment, students get an opportunity to observe their peers’ learning process and also be able to get a more detailed knowledge of their classmates’ work. This fosters increased responsibility in students, enabling students to be fair and accurate when assessing their peer’s essay, thereby making fair judgments, while also aiding in self-assessment of their own work.

Adrian also suggested the use of TeamMates, an online peer evaluation tool used by some of his colleagues in the Department of Chemistry, though he acknowledged that he is yet to try it personally. (refer to Technology in Pedagogy Series, No. 18, on “Leveraging peer feedback”).

5. Online tutorials

Adrian uses Camtasia Studio to create the online tutorials. These online video tutorials guide students through some of the main ideas discussed for a particular topic and allows them to work on their homework assignments without the need for them to attend his lectures. Other tools that are available at NUS to create such online tutorials and/or lectures are:

- Adobe Presenter (Breeze) and Adobe Presenter Video Creator,

- Camtasia Relay, and

- Ink2Go.

6. Learner response systems

Learner response systems can be used as a formative assessment to guide teaching, to measure what students are thinking and then address it immediately in class. They can be used to check students’ prior knowledge, probe their current understanding, and uncover student misconceptions. They can also provide feedback to the instructors about their students’ understanding and to students about their own understanding. These learner response system fall into the category of “taking technology into the classroom”. The two options that Adrian uses for this purpose are:

Some ways in which Adrian uses learner responses systems to integrate with the idea of scaffolding:

- Get students to answer the questions on an individual basis based on what is being discussed in class.

- Ask a question based on the lecture notes, but on a topic/concept that has not been discussed in great detail.

- Students can work in groups of 3-4 to answer the questions posed, and come back with a group answer.

- Get students to answer individually, and then work in groups to analyse the questions posed. Finally, get students to answer the question again individually.

The distribution of answers is then displayed immediately to the entire class. If the results show that a significant number of students chose wrong answers to a question, then the teacher can revisit or clarify the points he or she just made in class and if most students chose the correct answers to a question, then the teacher can just move on to another topic.

Q & A session

Following the presentation by Adrian, participants had the following questions:

| Q: |

Do you use the online quizzes as a formative or summative tool? If so how does it provide scaffolding? |

| AL: |

I use it as for formative assessment purposes. If you want students to tell you what they don’t know, then you cannot have a summative assessment. We would need to have formative assessment.

First, I allow students to take 5 allowed attempts, and as there are only 4 choices to each MCQ question, student should be able to get 100% by the fifth attempt. Second, I award only a participatory grade, and hence there is no pressure on the students to get it all right. The first attempt requires students to key in their rationale for choosing the answer. Based on the rationale, I am able to determine if students understand important concepts, and pin-point topics that students need further guidance. |

| Q: |

How do you decide on what type of questions to use in an online quiz, without understanding student’s prior knowledge? |

| AL: |

In designing the MCQ questions, experience with handling the course in previous years definitely helps. If it is the first time, then have multiple tier MCQs (with rationale) or have free text answers. Based on the answers that students give, and after a year’s worth of experience, we would then able to design better MCQs. |

| Q: |

When you use many technology tools in your course, do students complain? |

| AL: |

During my first class, I explain to my students as to why I use certain tools, and how they can benefit by using those tools. |

| Q: |

How much support is there for learner response systems in the literature? |

| AL: |

Current research has good support for the use of learner response systems. It really depends on how you use them. |

| Q: |

When you ask MCQ questions using learner response systems, can students share their answers with their peers? |

| AL: |

Students are developing a learning community. Although community learning helps, at times individual learning is equally important. Hence I would use all approaches – single answer; single answer after discussion with peers; group answer. |

| Q: |

How often do you use clicker questions in each lecture? |

| AL: |

I use about 1 or 2 questions per lecture. Students seem to appreciate the use of such questions in the classroom. I allow about 1-2 minutes for students to answer each question. |

Suggestions from group discussion

Following the Q & A session, Adrian posed the following questions for participants to discuss in groups as to how they employed instructional scaffolding in their own classrooms and disciplines:

- Do you use technology to scaffold your teaching?

- How do you employ scaffolding in your teaching?

- Why use technology to provide scaffolding?

- How does scaffolding support best practice in your classroom?

Adrian asked participants to ponder over how they get students cycle through their learning; and keep a record of their learning and progress. A summary of the group discussion is given below:

Online quizzes and feedback:

- Pre-lecture reading quiz

- Online survey forms: used more as a survey than as a quiz to collect a mid-term feedback from students.

Peer assessment / Peer feedback:

- An online form was used for collecting peer feedback for group work – using a grade (high, moderate, low) along with qualitative comments that gives reasons for providing that grade. Participants agreed that when students just know that there is peer assessment allows for a better behaviour.

- Participants also felt that the use of peer feedback moderates group behaviours, improves group dynamics, enhances their reasoning and rationalizing abilities and is also meant to avoid the free-rider problems in group work.

- It was also shared that to get students to reflect on their own learning and to improve the group dynamics, it is important to get students to sit down as a team and explain to each other what their contributions are. Generally it was felt that peer assessments are quite accurate—weaker students generally feel that they are better than what they are, while stronger students feel that they can do better. Once they talk to each other, weaker students tend remove the natural bias and tend to grade better.

Learner response systems:

Participants also shared other learner response tools that could be used other than clickers and questionSMS:

All of these tools can be used from any online platform and/or mobile devices.

Other useful ways of scaffolding:

- Facebook (FB) groups can be used for peer learning and peer review – students can comment and discuss; quiet students are more empowered to participate in the discussions, particularly since the FB space is one that students are familiar with and are comfortable using it. (refer to Technology in Pedagogy Series, No. 1 on Facebook for Teaching and Learning)

- Wikis / blogs can be used to get students to teach others as well learn from each other. (refer to Technology in Pedagogy Series, No. 2 on The Lunchtime Guide to Student Blogging and Technology in Pedagogy Series, No. 5 on Wikis for Participatory Learning). However, it was noted that some help and guidance is needed to get students to use wikis.

- YouTube videos to explain concepts

- Google docs to do peer work. (refer to Technology in Pedagogy Series, No. 3 on Google Docs and the Lonely Craft of Writing)

References

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education,

American Association of Higher Education Bulletin, 39, 3–7.

Ragupathi (2010). Using IVLE to implement the 7 principles of effective teaching. http://www.cdtl.nus.edu.sg/staff/guides/ivle-tip-sheet-2.pdf

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes, Harvard University Press, 86–87.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S. & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving, Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry, 17, 89–100.

Assessment + computer + network= Online assessment.

Assessment + computer + network= Online assessment.