Hi everyone,

Here’s the link for our rooftop garden report: tinyurl.com/wallflowersurban

All the best for your exams!

Wallflowers

Cherry, Dayna, Jeffrey & Joy

Hi everyone,

Here’s the link for our rooftop garden report: tinyurl.com/wallflowersurban

All the best for your exams!

Wallflowers

Cherry, Dayna, Jeffrey & Joy

Taking both this Urban Ecology module and Tropical Horticulture by Prof. Hugh Tan this semester, have caused me to reflect on urban vegetation in Singapore. What is the diversity of trees, and are all exotics bad for the ecosystem?

The city-state of Singapore is often portrayed as a utopia in terms of quality of life, economy, and sustainability. In fact, the Sustainable Cities Index 2016 ranked it first in Asia and second globally. On paper, the Sustainable Singapore Blueprint looks ideal. But environmental utopian models such as ‘eco-cities’ have poor track records when it comes to implementation. My question is: has Singapore managed to turn these environmental dreams into reality?

I conducted a research project on the biodiversity of NParks’ Nature Ways (NWs) for several months last year. A relatively new undertaking, NWs are stretches alongside roads planted with selected tree and shrub species that aim to “facilitate the movement of animals like birds and butterflies between two green spaces”. They are strategically located to 1) link biodiversity-rich areas to urban communities, 2) serve as wildlife habitats and 3) increase residents’ accessibility to nature. These green corridors beautify our immediate surroundings and are designed to inculcate greater appreciation of Singapore’s abundant (read: remaining) biodiversity.

These short routes may seem unlikely havens, given their locations — sometimes beside major four-lane roads — that are highly disturbed by both vehicular and foot traffic, besides regular maintenance by NParks’ stuff such as pruning (a necessity to prevent shrubs from becoming overgrown and thus inciting negative public feedback). However, over the course of several months, I was pleasantly surprised to come across several common and not-so-common butterfly and bird species, including the striking Tailed Jay (below, left). While relatively common, this species frequents treetops and is rarely spotted at ground level; presumably, it was attracted to the flowers of the nearby Ixora. I also recorded one sighting of the “Moderately Rare” (Khoon, 2010) King Crow (below, right).

Some photos of my other personal favourites are in the collage below. From top to bottom, in the left column: Leopard Lacewing, Blue Glassy Tiger, Peacock Pansy; right column: Brown shrike, Common flameback, and Yellow-vented bulbul.

While these sightings indicate that certain species do utilise the NWs for forage and shelter, these are largely limited to the common ones, generalists with a wide range of suitable caterpillar host plants or food sources.

I believe that this is one way the NWs can be improved upon. Instead of further expanding the already extensive habitat of the generalist species, more focus could be placed on enhancing these locations to increase their suitability as habitat for other species — for instance, by planting a greater selection of host plants, as was done to great success at the Alexandra Hospital butterfly trail in the past.

This is also a good opportunity to introduce a new citizen science programme centred on the enhancement of biodiversity on NWs. This could be targeted at nearby residents, who will directly benefit from improvements made to these areas, and for whom the volunteering programme would be relatively accessible. It would entail the provision of caterpillars of less-common species (bred from local stock where possible) to the volunteers, who would rear and release them upon eclosion. Leaves of the host plants could be obtained from the NWs to feed the caterpillars. To maximise resident involvement, a poll could be conducted before the commencement of the project allowing residents to vote for their preferred species to care for. This being a child-friendly project, it would also help cultivate interest and curiosity for nature in the young, which is an important step towards a nation of like-minded people who care for the environment.

References

Khoon, S. K. (2010). A field guide to the butterflies of Singapore. Singapore: Ink On Paper Communications Pte. Ltd.

As we all know, the fragmentation of natural habitats is one of the many repercussions brought about by urbanisation. Roads especially, have both positive and negative impacts, the latter being the increased likelihoods of roadkill and the former being increased connectivity.

While the benefits for us are clear, there has yet to be any significant benefits for wildlife in general (Fahrig & Rytwinski, 2009).

Singapore is known for its extensive green cover, where even the roads and highways are lined with trees and shrubs. Although this helps to ameliorate the impacts of the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, it might inadvertently attract more animals to the vicinity, increasing the chances of roadkill; with the ubiquity of street lights in Singapore further exacerbating the issue.

Roadkills in Mandai

The recent reports of roadkills (a Leopard cat, Sunda pangolin and Sambar deer) showed a worrying trend [Animals affected by Mandai park works: Wildlife groups; March 24, 2018]. Mammals are uncommon in Singapore, with small mammals making up the majority of the population. It does not help that smaller vertebrates—which are already threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation—were found to be at greater risk of roadkill (Rodríguez-Castro et al., 2017).

It was heartening to know that in addition to the proposed eco-link bridge, several other structures (e.g. green acoustic wall barriers) that protect and facilitate the movement of wildlife would be built, including the retention of existing culverts (MPH, 2016). However, current mitigation measures—like road signs and speed bumps—are still inadequate as wildlife in the vicinity have no structures to aid their movement across the temporary fauna crossing, rendering them vulnerable to vehicular strikes.

Apart from mammals, birds should be taken into consideration during the implementation of mitigation measures as well. Despite (most birds) having the ability to fly, some birds are territorial and rely on their songs to find potential mates, thus noise pollution would affect their hearing, forcing them to go closer to roads. Light pollution from street lights and vehicles pose threats too, as migratory birds often rely on starlight for navigation, hence rendering them vulnerable to collisions (Glista et al., 2009).

Animals in the vicinity are already facing significant levels of stress from the construction works and shepherding; ergo, relevant authorities should not be complacent, and look into enhancing roadkill mitigation measures by consulting nature groups for further improvements. Emulating its predecessor (Eco-Link @ BKE) should be a given, but there are definitely areas that could still be improved upon. Beneficial design elements from other wildlife crossings, like the Sungai Yu wildlife corridor and Banff National Park, should be taken into consideration for incorporation into Mandai, as well as future projects.

If we truly wish to bask in the beauty of nature and reap its benefits, the onus is on us to retain, or better yet, enhance the connectivity in our highly disturbed environment, with inconveniences borne by us and not the wildlife.

Towards a “car-lite” society

On the other hand, the suggestion to designate Mandai Lake Road as a ‘car-lite’ zone is a feasible one and should be taken into consideration [Make Mandai vehicle-light to reduce roadkill; Mar 29, 2018]. After all, Singapore is in the process of shifting to a ‘car-lite’ society, and has in fact designated some areas of the upcoming Tengah estate to be ‘car-free’ [New Tengah HDB town heavy on greenery, light on cars; Sep 9, 2016]. The Jurong Lake District has also been designated as a ‘car-lite’ area as well [Fewer car parks, more cycling paths in Jurong Lake District; Aug 25, 2017]. With a car-lite society, roadkills would hopefully be reduced, if not kept to a minimum.

Another suggestion would be abolishment of the car park in the East Arrival Node, which is situated near the Central Catchment area (MPH, 2016). Having a single carpark outside of the sensitive Central Catchment area, with designated buses shuttling visitors in and out of the wildlife park would significantly reduce traffic along Mandai Lake Road, and hopefully, roadkill incidents too.

Roadkills, regardless of the conservation status of the animal, are detrimental to Singapore’s sensitive ecosystems. For this reason, I implore Mandai Park Holdings (MPH), the parent company behind Wildlife Reserves Singapore (WRS), to make roadkill statistics available to nature organisations and institutions, so that they can analyse the data and provide constructive feedback. In highly urbanised Singapore, incidents of roadkill are bound to occur, even with robust mitigation measures. I hope that authorities can learn from the mistakes of Mandai, and put more measures in place for the upcoming Tengah estate, in order to best preserve what precious little wildlife Singapore has left.

References

Fahrig, L. & Rytwinski T. (2009). Effects of roads on animal abundance: an empirical review and synthesis. Ecology and Society 14(1): 21. Retrieved from: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss1/art21/

Glista, D. J., DeVault, T. L., & DeWoody, J. A. (2009). A review of mitigation measures for reducing wildlife mortality on roadways. Landscape and Urban Planning. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2008.11.001

Mandai Park Holdings [MPH]. (2016). Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report. Mandai Park Holdings. Available at: https://www.mandai.com/download/pdf/Final%20EIA_Main%20Chapters.pdf (Accessed 14 April 2018).

Rodríguez-Castro, K. G., Ciocheti, G., Ribeiro, J. W., Ribeiro, M. C., & Galetti, P. M. (2017). Using DNA barcode to relate landscape attributes to small vertebrate roadkill. Biodiversity and Conservation, 26(5), 1161–1178. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1291-2

Golf courses can increase property values and contribute to economic growth. They also attract wealthy tourists and are recognised as useful sites for business deals. The vast green spaces and well-maintained turf can be aesthetically appealing to some people and provide recreation.

With over 1,500 hectares (approximately 2%) of Singapore’s land area covered by 17 golf courses, there are concerns that they are taking up too much space and are environmentally unsustainable. In this article, I address these concerns and Singapore’s plans.

Environmental impacts of golf courses

Golf course management involves the use of pesticides and fertilisers, which can contaminate the environment (including water bodies), although mitigation measures are already in place. The use of pesticides and fertilisers is controlled and regulated by Public Utilities Board (PUB), and products are limited to a list of approved chemicals. But golf courses are also heavily irrigated. Even though this water comes from water bodies that collect rainwater, and water recycling is widely practiced, it takes a lot of energy to water the turf, in addition to what’s required for overall maintenance of the golf course (e.g., machinery).

Golf courses can also support biodiversity because they are home to species that are adapted to fragmented tree patches and open areas. In some instances, they can even enhance biodiversity, like in Tanah Merah Country Club, where planted, exotic vegetation attracts birds, such as red jungle fowl and herons. But that typically only happens in golf courses built on barren, reclaimed land. For golf courses built on non-reclaimed lands, the disturbance to the natural habitat can be extensive.

Although golf courses inevitably have detrimental impacts on the environment, the sustainability of their practices are improving with time.

So, what’s next

Based on the Ministry of National Development’s Land Use Plan released in 2013, over 200 hectares of golf courses will be freed up for other uses. Two golf courses (Jurong Country Club and Raffles Country Club) must vacate their premises by August 2017 and July 2018, respectively. There will be no new lease offered to some others, including Marina Bay Golf Course, Keppel Club, and Champions Public Golf Course. This is a welcome change, especially given that the 1999 Land Use Plan included up to 29 new golf courses. It seems that the government recognises the concern that golf courses take up too much space, especially considering that less than 1 % of the population plays golf.

However, do fewer golf courses mean more housing development? According to the 2013 Land Use Plan, land allocated to parks and nature reserves will increase from 5,700 hectares in 2010 to 7,250 hectares in 2030. Furthermore, the projected increase will mainly come from urban parks in housing estates. This may seem promising because residents use urban parks more than golf courses. But do urban parks hold higher ecological value? This warrants further studies on comparing the ecological values between urban parks and golf courses. While the death of some golf courses frees up land for development and more parks, it is important to note that quality, not quantity, of green spaces matters.

References

Soh A (2014) 200 ha of golf course land freed. The Business Times. http://www.businesstimes.com.sg/top-stories/200-ha-of-golf-course-land-freed

Colding J & Folke C (2009) The role of golf courses in biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management. Ecosystems, 12: 191−206.

Heng J (2017) Fewer golf greens, but more greenery from parks and trails. The Straits Times. http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/fewer-golf-greens-but-more-greenery-from-parks-and-trails

Ministry of National Development (2013) A high quality living environment for all Singaporeans. Land use plan to support Singapore’s future population. Ministry of National Development. https://www.mnd.gov.sg/landuseplan/e-book/files/assets/basic-html/index.html#page1

Neo H (2001) Sustaining the unsustainable? Golf in urban Singapore. The International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology. 8(3): 191−202.

Neo H (2010) Unpacking the Postpolitics of Golf Course Provision in Singapore. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 34(3): 272−287.

Coney island is a small island, spanning approximately 2km. It used to be much smaller, but land reclamation efforts beginning from 1975 had expanded the land area by almost 5-fold, to its’ current size (source). The natural state of the island was barely disturbed, in hopes of retaining the rustic feel of the island. Renovations to construct toilets and other amenities were done so with minimal disturbance and utilised environmentally friendly features such as toilets that flush with rainwater, solar-powered water pumps, and also recycled timber to construct bridges and benches. It was opened up to the general public in 2015. It was home to a large number of animals, birds, and plant species. Even the 2 native surviving species of Cycads which have lost their ‘homes’ in urban Singapore was relocated to Coney Island (source). Even when visitors complained of the sandfly infestation, NParks refused to intervene, mentioning that it was intentional that they left the place as ‘natural’ as it was (source). I personally feel that Coney Island is a place that they should refrain from unnecessary development, but still allow visitors to enter the island. Basic amenities such as bins, shelters, and toilets should continue to be maintained to allow visitors to have enjoyable visits, but I do not agree with allotment of land to build residential estates.

Disclaimer:

There haven’t been any studies done on the arthropods of Coney Island, neither can I provide the most reliable information. However, I am a frequent visitor of the island, with weekly visits last year and monthly visits this year. As I am armed with my camera with each visit, I pay close attention to the arthropod diversity on the island, and walk the same paths during each visit, approximately at the same time of the day for each visit. Hence, I do keep a record of the arthropod diversity through photographs (to the best of my ability) and through observations. As a disclaimer, I mainly focus on mantid diversity, but do make other observations too. As there have been absolutely no published study on local mantids, I can only rely on my own experiences and observations in Singapore, amounting to more than 5 years, to make statements and claims.

Before Construction:

Ever since construction of residential estates began in early 2018 according to the land use plan (source), I have observed major changes in Coney Island. For the mantids, Odontomantis sp. and Tenodera sp. used to be the only two mantid species observed before construction began.

(Above: Odontomantis sp. 1st instar nymphs)

(Below: Odontomantis sp. adult female)

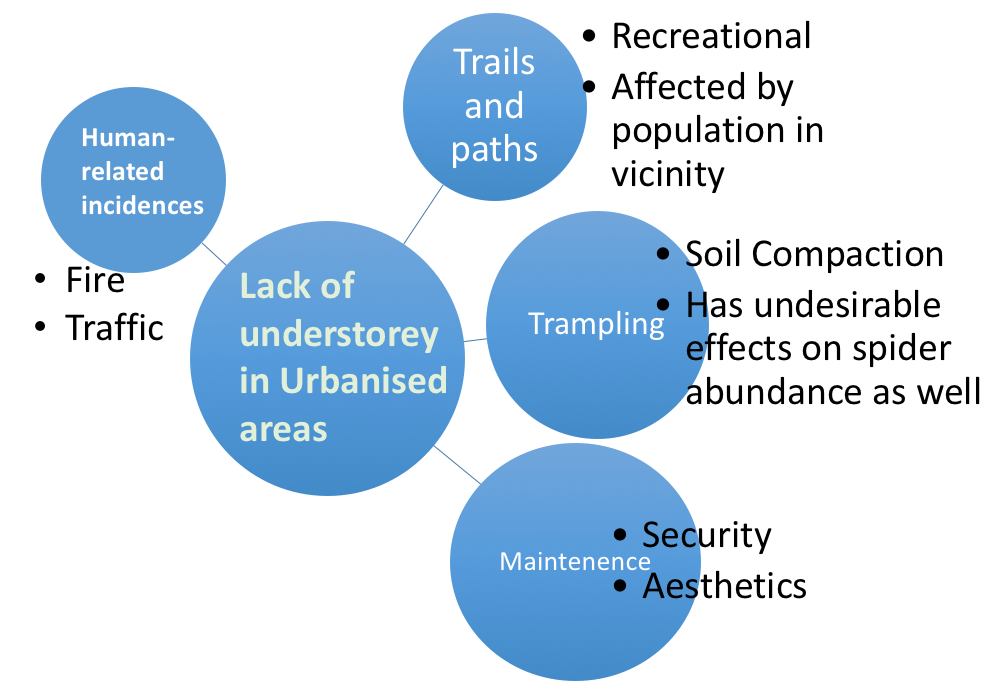

Following lectures on urban plants, I was curious to know more about the significance of a lack of understorey/ shrub/ herb/ ground layer in urban forests. Hence, this post is dedicated to answering two questions: Why is there a lack of understory/herb/shrub layer in urban forested areas, and what are the implications of this?

Why is there a lack of understory/herb/shrublayer in urban forested areas?

The effect of urbanisation on the types and patterns of vegetation in the city is very pronounced, and has resulted in its own unique mix of species, community compositions and structures. In terms of structure, urban forests have a more simplified structure. There is often a lack of understorey, herb/shrub layer as well as ground layers. For native species in the ground layer of parks, this is attributed in part to the high levels of disturbance caused by making paths and maintaining vegetation (Guntenspergen et al., 1997).

There is high maintenance of branching vegetation like shrubs in the understory, to increase visibility in green spaces, as well as to look aesthetically pleasing. Increased security linked to increased visibility is more attractive and important to residents and also visitors of the city (Sieghardt et al., 2005). Also, heightened levels of disturbance like human trampling resulted in poorer root development and stem growth (Bhuju & Ohsawa, 1998). Other reasons include disturbance caused by construction of trail or trekking paths. Including Singapore, as nature trails become more popular as a recreational activity in developed countries, disturbance by trampling might become increasingly detrimental to the diversity and growth of the understory because of soil compaction (Bhuju & Ohsawa, 1998). The number of people who live in the vicinity of forest stands is also important in estimating the amount of trampling that affects understorey health, because of increased recreational visits, as demonstrated in Greater Helsinki, Norway (Malmivaara et al., 2002). Singapore, as a highly populated area with a population of almost 6million compared to 1.4million in Greater Helsinki probably means that there is higher frequency of visitorship in forested areas, and hence greater disturbance. Trampling seems to affect plants more than invertebrate fauna, and among invertebrate fauna, spiders suffer the most from trampling effects (Duffey, 1975). In New York City, studies done in several urban parks show that disturbances caused by traffic and fires resulted in the lack of ground layer and seedlings (Guntenspergen et al., 1997).

Ecological implications

The presence of a shrub layer increases or maintains the biodiversity in the understorey by being competition for fast-growing opportunistic species that might otherwise take over places with large canopy gaps that let sunlight reach lower heights of the forest (Beckage et al., 2000). This allows for other plants with different life histories and trade-offs to grow, resulting in a more diverse species community. With increased diversity of flora, this increases the number of different niches that can be exploited by animals like arthropods and birds in the understorey. The understorey has a big role in nutrient recycling as well, cycling a greater proportion of its total nutrient (N, P, Ca, Mg, K, Zn, Cu) annually compared to overhead vegetation (Yarie, 1980). A thick understorey can also act as a buffer that softens edge effects especially when forests are next to incompatible land-use, which is often the case in Singapore (Smardon, 1988). Hence, with reduced or absence of these layers in urban forests, forest dynamics are significantly altered, and such benefits are not available.

However, the lack of an understorey has its own benefits too. In a forest study in West Japan, canopy pine trees were shown to suffer from reduced physiological stress when there is a lack of understory because of a lowered level of competition for water and nutrients (Kume et al., 2003). Dense understories also proved to retard forest succession in a meta-analysis by Royo & Carson (2006). A study by Guntenspergen (1997) did not even show significant differences in shrub/ herb layer in terms of presence, composition nor species diversity across an urban gradient. They attributed this to lower visitorship of the forest fragments. As for the understorey component in the same study, there were changes in composition, but the authors attributed it to a combination of both fragmentation in addition to disturbance in urban areas.

References

Beckage, B., Clark, J. S., Clinton, B. D., & Haines, B. L. (2000). A long-term study of tree seedling recruitment in southern Appalachian forests: the effects of canopy gaps and shrub understories. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 30(10), 1617-1631.

Bhuju, D. R., & Ohsawa, M. (1998). Effects of nature trails on ground vegetation and understory colonization of a patchy remnant forest in an urban domain. Biological Conservation, 85(1-2), 123-135.

Duffey, E. (1975). The effects of human trampling on the fauna of grassland litter. Biological Conservation, 7(4), 255-274.

Guntenspergen, G. R., & Levenson, J. B. (1997). Understory plant species composition in remnant stands along an urban-to-rural land-use gradient. Urban Ecosystems, 1(3), 155.

Kume, A., Satomura, T., Tsuboi, N., Chiwa, M., Hanba, Y. T., Nakane, K., … & Sakugawa, H. (2003). Effects of understory vegetation on the ecophysiological characteristics of an overstory pine, Pinus densiflora. Forest Ecology and Management, 176(1-3), 195-203.

Malmivaara, M., Löfström, I., & Vanha-Majamaa, I. (2002). Anthropogenic effects on understorey vegetation in Myrtillus type urban forests in southern Finland. Disturbance dynamics in boreal forests: Defining the ecological basis of restoration and management of biodiversity.

Royo, A. A., & Carson, W. P. (2006). On the formation of dense understory layers in forests worldwide: consequences and implications for forest dynamics, biodiversity, and succession. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 36(6), 1345-1362.

Sieghardt, M., Mursch-Radlgruber, E., Paoletti, E., Couenberg, E., Dimitrakopoulus, A., Rego, F., … & Randrup, T. B. (2005). The abiotic urban environment: impact of urban growing conditions on urban vegetation. In Urban forests and trees (pp. 281-323). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Smardon, R. C. (1988). Perception and aesthetics of the urban environment: Review of the role of vegetation. Landscape and Urban Planning, 15(1-2), 85-106.

Yarie, J. (1980). The role of understory vegetation in the nutrient cycle of forested ecosystems in the mountain hemlock biogeoclimatic zone. Ecology, 61(6), 1498-1514.

The air was sour this side of the stone tree forest, right next to the thunderpath. The tomcat quickly scent-marked a stone tree despite his scent being overwhelmed by the pungent breath of the loud shiny beasts, for it was in his nature to mark his territory. He made the pass as quickly as possible, hurriedly slinking back into the sheltering stone spires of the white stone trees.

It was safe neither in the forest nor outside it, for outside he had to beware the two-legs and their beasts, while within the stone tree forest he had to watch out for its other inhabitants. They all shared the same stone tree forest; with too many of them in this small space there were always fights for territory. He usually won, for unlike the other cats he was still whole, and still had his fighting instinct within him.

When passing the dawn-ward border the tom made sure to mark it well, for on the other side was the territory of another tomcat, still whole and a fierce fighter. Their fight over this border two sunrises ago had left his claws sore. It was an intense battle, and despite the threat the tom loved the thrill of the battle. He made a quick pass by the shallow stone creek that ran along the edge of the stone tree for a drink before resuming his patrol.

The dusk-ward border was different. Here, the halfs shared the space. These cats were not normal anymore, not whole. They were changed after being caught by the two-legs and were never whole again. Their ears were clipped, not torn from battle but a clean cut of a two-leg’s touch. The tom knew he could exert his strength and expand his border into the territory of the halfs; they were weak and non-breeding, lacking the fire that made a tomcat, well, a tomcat. He knew they would not fight back. He took his border over by two tail-lengths and sprayed his scent markers over the spires of the stonetree.

There were more and more halfs these days, growing fat on false two-leg food and slinking up to their grubby hands begging for more. It was like the halfs had lost all sense of being a cat. They were unnatural, unable to breed or hunt and reliant on two-legs for protection. Some even slept within the two-leg nests higher up the body of the stonetree.

Unlike them, the tom was whole and strong, and felt a stirring to breed. He was getting restless, it had been many moon cycles since he had last bred a female. Not for the lack of trying, but all the females, while they still smelt whole, were unable to bear kit. They bore the marked ear of one touched by two-legs. One day, he would find a truly whole female.

There were always new cats coming in, brought in by the two-legs. They were weak and died easily when the two-legs did not bring food, for the halfs had forgotten how to hunt. The tom and his neighbour would meet the new cats in stride, whipping them submissive and out of their territories so that they would learn to not trespass. While the tom could not overpower the other in their battle for territory, he was unusually grateful for the rivalry, to have another whole tom with him amongst the shame of halfs.

– Excerpt from a potential cat anthropomorphism novel idea, depicting the strays living under HDB blocks.