This page explains what to look out for in academic writing by using videos and examples to illustrate each explanation. There are five main sections below:

1.0 Academic Essay (Types of Essays)

2.0 Structure of an Essay ( Introduction – thesis; Body – topic sentence, supporting details, concluding sentence); Conclusion)

3.0 Academic Tone (Dos and Don’ts)

4.0 Difference between Formal and Informal Writing

5.0 Reporting verbs and citation style (Journalistic and Academic writing)

1.0 Academic Essay

What is an academic essay?

An academic essay is usually based on an all-encompassing idea developed throughout the whole text with the aim of informing or persuading the reader using scholarly evidence.

There are different essay types or genres such as argumentative, descriptive, expository and narrative essays.

2.0 Structure of an Essay

What is the structure of an essay? (Video)

2.1 Introduction

The introduction answers the fundamental “What’s in it for me?” question that every audience asks when faced with the time-consuming task of reading a text from start to finish.

Answering this question as quickly as possible ensures that your audience stays with you. It is therefore essential that you ease your readers into the subject of discussion with a broad overview to prepare your reader for the very specific discussion you will want to have in the body of your essay.

The next section will explain how this can be done.

2.1.1 How do I put an Introduction together? (Video)

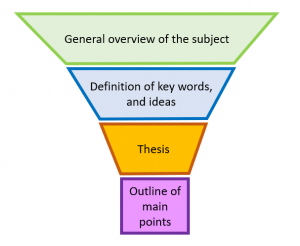

A strong introduction eases the reader into the subject by discussing the familiar and then moving into more specific and new information. In the funnel-shaped illustration below, you will see that the parts of the introduction begin broadly before narrowing down to a central point, the thesis. At this point, the introduction needs to widen its scope again to discuss the central points of the essay.

The thesis is usually introduced towards the end of the introduction. This should be followed by a brief outline of the main points. Some introductions include a transition sentence that leads into the rest of the essay. An example of an introduction can be seen here.

2.1.2 How do I provide background information?

Reading an essay that launches straight into its thesis, or central argument, can be a confusing experience for most readers.

Writers who provide background information in their introductions do so with the aim of anticipating what information their readers want. (Video)

Here is a list of information that might be included as background information:

- descriptions of a particular situation or problem

- where (location) and when (time span) the subject/problem occurs

- brief summaries of the history of the subject

- statistics that indicate the significance of the problem

- concrete examples that illustrate the significance of the problem

- clear definitions that explain key ideas, concepts and terms that will appear in the thesis

2.1.3 How do I construct a thesis?

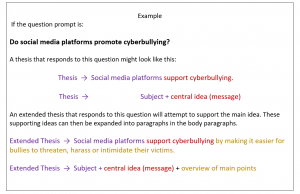

A thesis is usually made up of two main parts:

- the subject of discussion

- the central idea

An extended thesis might include a third part:

3. the overview of the main points of the essay

Where there is a question prompt, a thesis will provide a direct answer to the question and this is followed by an overview of the main supporting points which will be elaborated on later in the body paragraphs.

You can also find out more about how to construct a thesis statement by responding to key words in a question prompt.

2.2 The Main Body (Video)

The main body of an essay expands on the thesis statement. It is made up of one or more supporting paragraphs.

As you can see, each paragraph in the main body basically consists of these three elements:

- A topic sentence

- Supporting details

- A concluding sentence

Each paragraph should have only one main point. This is expressed in the topic sentence. The topic sentences in each paragraph of an essay support the thesis statement. In turn, the supporting points in each paragraph expand on the topic sentence.

Now, let us look more closely at the different parts of a supporting paragraph.

2.2.1 Topic Sentence

The topic sentence summarizes the main idea of the paragraph so that you, the reader, know what to expect to find in the ensuing sentences. As such, the topic sentence is usually, but not always, found at the beginning of a paragraph. It is closely linked to the thesis statement and tells you more about it. Without a topic sentence, it would be hard to tell what the main idea of a paragraph is.

2.2.2 Supporting Paragraph

2.2.2.1 Structure of a Paragraph (Video)

What follows the topic sentence are the supporting details: explanation, examples, evidence from sources, and interpretation. Read a body paragraph written about student procrastination.

As you read, identify the following:

- The topic sentence

- Explanation

- Evidence from sources

- Interpretation /Analysis

2.2.2.2 Giving Explanation

There are different types of explanations: exemplification, cause-effect, problem-solution and comparison-contrast.

2.2.2.3 Writing Coherently

In writing, it is important to present the relationship between ideas clearly and logically, so that your reader can better understand the message that you are trying to put across. There are several ways to do this:

2.2.2.3.1 Using transitions or link words to join sentences.

- Making your writing coherent

- Using transition and linking works

- Using appropriate transitions

- Linking words – common errors (Video)

2.2.2.3.2 Linking new information with previously mentioned information

2.2.2.3.3 Repeating nouns and pronouns

- Pronouns – common mistakes (Video)

2.2.2.4 Combining ideas within sentences

Exercises: Read two body paragraphs of an essay about the effects of video gaming and identify the features that help to make the writing coherent:

- Linking words

- Linking new information with previously mentioned information

- Repeating nouns and pronouns

- Combining ideas with sentences

2.2.3 Concluding Sentence

Not all paragraphs have a concluding sentence, but when they do, the concluding sentences normally do one or more of the following:

- Summarize the main point

- Link the current paragraph with the next paragraph

- Qualify the viewpoint given in the elaboration

Read two paragraphs which end with concluding sentences. Identify the concluding sentences and the type of information that is in there.

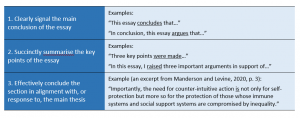

2.3 Conclusion (Video)

A conclusion is an important part of the essay to bring the key points of your body paragraphs into a unifying whole — the main argument.

To conclude your essay, you should:

- reinforce your thesis

- reiterate your key ideas or findings

- highlight, if any, significance, implications and future trends

3.0 Academic Tone

Here are some Dos and Don’ts to consider when writing your essay.

4.0 Difference between Formal and Informal Writing

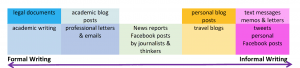

Academic writing requires a formal, structured style. By contrast, other genres of writing may allow for a more casual tone and structure.

Personal communication between equals, such as text messages and emails, may call for the most informal and casual of styles, while academic writing demands a formal, judicious style. Journalistic writing, blog posts and other seemingly formal kinds of writing fall somewhere in between. To sum up, your audience—Who are you writing for? —and the subject matter —What are you writing about? — determines how formal your writing should be.

4.1 Formal and Informal Language

Your diction, or choice of words, is particularly important in ensuring that your writing is formal. Colloquial language, such as slang and internet abbreviations, signal a casual tone that has no place in most academic papers. You should also avoid overused phrases (clichés) and exaggerated language (hyperbole).

5.0 Reporting verbs and citation style

Students typically associate “reporting” with journalism. After all, journalists are often called reporters. Reporting, however, goes beyond the domain of journalism. It is a particularly crucial and essential skill in academic writing.

Academic reporting and journalistic reporting are similar in several ways. For instance, they both adopt a formal style, largely devoid of colloquial words or expressions. Academics and journalists also tend to investigate and report on many similar issues – scientific, political, economic, and social, among many others. However, academics and journalists differ largely in the ways they report on these issues.

5.1 Comparing verb usage between journalistic and academic reporting

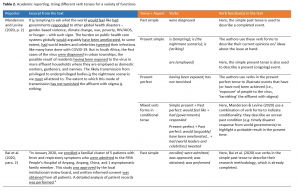

One major difference between academic reporting and journalistic reporting lies in how academics and journalists use verb tense and aspect. (For a detailed definition and explanation of verb tense and aspect, see Sections 4.2.1 and 4.2.2. in “Essential Grammar”)

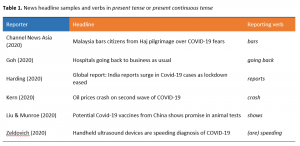

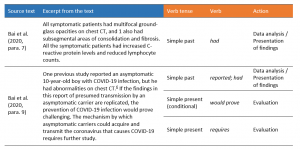

Journalistic reporting is almost always situated in the present time. Reporters tend to write about present or relevant issues in a manner that conveys them as ongoing or developing. Writing about ongoing/developing issues requires the use of the present or present continuous verb tenses, especially in the headlines of news articles, as illustrated in Table 1 below:

Meanwhile, academics can only reliably publish their reports after months or years of research. Hence, most of their writing reflects work that is already completed or is still ongoing, but has gone through several phases of work or research. This kind of formal reporting requires a wider variety of tense and aspect: past simple, past perfect, present simple, and present perfect, among other. (See Sections 4.2.1 and 4.2.2 for a detailed explanation of these terms.)

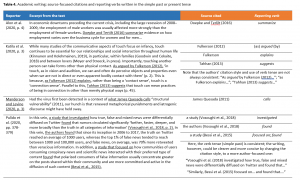

Table 2 below provides several examples of verbs, written in different tenses, used in a variety of ways in academic writing.

5.2 Different types of citation styles

5.2.1 Journalistic reporting: Source-focused citation style

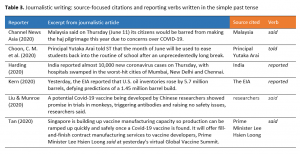

Journalists and academics are quite similar in their use of verb tense when citing from sources. In journalistic writing, it is important to not only report relevant and timely information, but also to properly cite them, especially if they have been obtained from external sources.

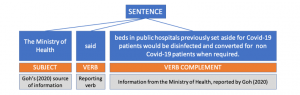

When journalists deliver news, they typically use reporting verbs in the past tense. To illustrate these points, let us examine a sentence from a Straits Times article written by reporter Timothy Goh (2020):

Goh (2020) uses the reporting verb said to report an official statement from the Ministry of Health (MOH). Notice that Goh, as a journalist, does not claim this statement to be his; he correctly cites the source of the statement (i.e., MOH). By using the verb said, he accurately describes what MOH did: they gave a statement about the use of hospital beds previously set aside for Covid-19 patients.

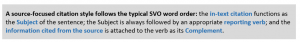

Note that when Goh (2020) cites the source and uses the verb said, he uses in-text citation (i.e., The Ministry of Health) as the Subject of the sentence. This is an example of a source-focused citation.

Definition: A source-focused citation places the cited author, i.e., the in-text citation, as the Subject of the sentence/clause. This citation style requires the use of an appropriate reporting verb.

5.2.2 Academic reporting: Source-focused (Author-Date) citation style

Academics, like journalists, are also required to cite from sources to strengthen the credibility of their research and the validity of any claims or arguments they make. Without these sources, it becomes hard for any student of academic writing to present arguments in a credible and persuasive manner.

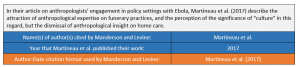

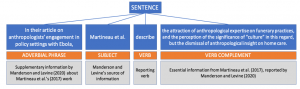

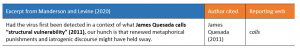

To emphasise the importance or relevance of a source text, academics use a source-focused citation style. The academic version of this style, however, differs from the journalistic version. Academic writers use the Author-Date format, which requires the source’s author name(s) and year of publication. To illustrate this, let us use a sample Author-Date citation written by Manderson and Levine (2020, p. 2):

Using a source-focused, Author-Date citation style, Manderson and Levine correctly cite their source of information, i.e., Martineau et al. (2017). Moreover, they use an appropriate reporting verb, i.e., describe to accurately portray what Martineau et al. talked about in their 2017 paper.

Citing academic and non-academic sources

The above excerpt from Manderson and Levine (2020) illustrates a conventional way of citing sources. This citation style uses the in-text citation as the Subject of the sentence (i.e., Martineau et al., 2017). The in-text citation is then followed by the reporting verb, i.e., describe. The final part of the citation is the Verb Complement of the sentence, which summarises or paraphrases the information borrowed from the academic source. The diagram below illustrates the sentence structure of the citation style:

For more information on adverbials and adverbial clauses, read Section 8.2.1 in Essential Grammar.

Citing non-academic sources

Generally, the above formulae also apply to non-academic sources like news reports. You need to place the name of your non-academic source, i.e., in-text citation, as the Subject of your sentence; use an appropriate reporting verb; and attach the cited information after the verb.

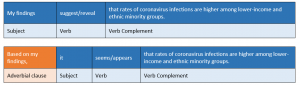

Citing yourself

It is common in academic writing to cite yourself when you are trying to make an argument, or analyse/present your own findings. For example:

Notice in the above examples that the order of elements (adverbial clause, Subject, Verb, and Verb Complement), also follow the typical SVO word order in English.

Summary

For more examples of source-focused academic reporting, see Table 4 below.

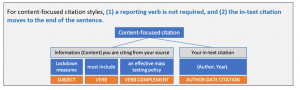

5.2.3 Academic reporting: Content-focused citation style

Citing from sources can also be done by using a content-focused citation style. This style, as the name suggests, focuses on the information that is derived from a source text by placing the in-text citation at the end of a sentence or phrase.

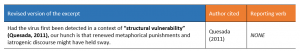

To illustrate this, let us first review the citation style adopted by Manderson and Levine (2020) in Table 4 (Section 5.2.2):

The citation style adopted above is source-focused; however, we can also write the same citation in a content-focused style:

In shifting the citation style’s focus from the author to the content, two things occur:

- the reporting verb calls disappears, and

- the in-text citation moves to the end of the sentential clause.

Summary

5.2.4 Choosing the right citation style

As the name suggests, source-focused citation styles emphasise the importance or relevance of your sources to your essay. Use this citation style if you need to highlight relevant publications or scholars that have made significant contributions to a particular area of research. This type of citation style is also good for comparing scholars who have similar or differing views on a particular scholarly issue.

If your intention is to highlight ideas, concepts, or arguments, a content-focused citation is preferred. This citation style is generally good for summarising multiple ideas/concepts in the same paragraph.

5.3 Three functions of academic reporting

As a university student, you should bear in mind the three functions of academic reporting:

Reviewing relevant academic literature

- Academic research is always historical; if you are an undergraduate writing on a certain research topic, it is almost guaranteed that you will be able to trace your topic back to relevant research works already found in the literature. If you are writing an academic essay, you need to include relevant works and report/comment on them.

Critically evaluating the literature:

- Academic writing is a form of engaging in a debate or discussion with your audience. Many researchers publish their works for the purpose of corroborating or disproving findings, ideas, or arguments/claims of other researchers. Your professors and instructors will always be interested to see how you would report and evaluate these things.

Reporting and evaluating your own research, ideas, and findings:

- For laboratory reports and longer essay projects like theses and dissertations, your professors and instructors may require you to conduct your own research. This means that you will need to report your methods, data analysis and findings and critically evaluate them based on the current academic literature.

NOTE: Aside from the three functions of academic writing, you should note that different disciplines have their own preferences and citation styles. Ultimately, you should check with your professors, tutors, and faculty to find out which citation styles are conventionally used within your discipline.

As mentioned in Section 5.2.2, source-focused citation styles require the use of appropriate reporting verbs.5.4 Source-focused citation style: Using the appropriate reporting verb

5.4.1 Sense (Meaning)

Choosing the right reporting verb requires you to understand the general sense (meaning) of verbs. As discussed in Section 4.1 in “Essential Grammar”, verbs can be dynamic (denoting an action) or stative (denoting a state or being).

If you are citing a scholar in your report or essay, you can decide which reporting verb to use by identifying whether the scholar is performing a dynamic action (e.g., experiment, survey, conduct, test) or is expressing a state or being (e.g., think, believe, surmise, consider, become, seem, appear).

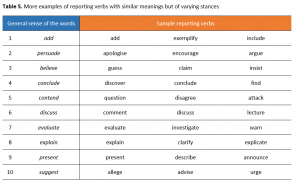

Table 5 below provides several examples of reporting verbs you can use for source-focused citations. They have been arranged based on their similar senses.

5.4.2 Stance

As a university student you might, at times, find it challenging to use reporting verbs appropriately in a written assignment. To address this issue, you must identify and understand the “stance” – that is, the position that an author takes in relation to an idea, concept, argument, or claim.

Figuring out a person’s stance will help you, as a writer, to accurately report or evaluate their ideas, concepts, arguments, or claims in your own writing.

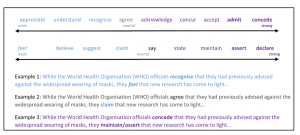

You can identify someone’s position on a certain issue based on the following categories: weaker, neutral, and stronger. The three sets of reporting verbs – agree, say and study- are the most commonly used in academic writing. However, their synonyms may more accurately reflect your opinion of the authors that you wish to cite in your writing:

Looking at the above examples, the reporting verbs concede, agree and understand are related in the sense that they indicate some degree of agreement. The choice of reporting verb expresses your view of the source material.

In Example 1, the use of the weaker reporting verbs recognise and feel indicate the writer’s doubts regarding the credibility of the information presented by the source (the WHO officials).

In Example 3, the stronger verbs concede, maintain and assert are used. The WHO’s ability to concede—admit an error—and their more definite assertion of the new research suggests that the writer has a more positive view of the organisation.

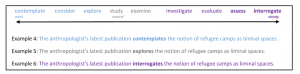

Examples 4, 5, and 6 demonstrate how changing the reporting verb in a sentence can reflect a writer’s attitudes towards the sources that are cited. In Example 4, contemplates suggests that the writer does not believe that the anthropologist’s work is rigorous. By contrast, the verb interrogates indicates a degree of admiration for the anthropologist’s scholarship.

Journalists and academics who are sensitive to nuances in people’s actions or statements are more likely to accurately reflect their stances in writing. As a university student, it is your responsibility to adopt the same level of sensitivity to the things you read and write about. Developing a strong awareness of the varying beliefs that people hold, as well as the positions they take on certain issues, will help your writing become more accurate, credible, and reliable.

5.5 Variation in the use of verb tenses in an academic paper

A typical university-level academic paper has three major parts: introduction, middle, and conclusion. These different parts fulfil various functions; hence, we would naturally assume that there are variations in the way we write them.

We can see this variation in the use of verb tenses.

5.5.1 Introduction section

An essay introduction typically contains the following: (i) general statements to interest a reader in the topic, (ii) definition and explanation of terms, (iii) contextual information, and (iv) a thesis statement.

Parts (i) to (iii) tend to be expository in nature, so academic writers are generally free to use a variety of tenses and grammatical aspects in this section.

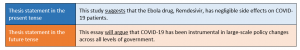

For (iv), however, the main verb of the thesis statement is usually written in the present tense, although in some cases, academic writers prefer to write their thesis statements in the future tense. The two sample sentences below reflect this variation:

Both forms are acceptable, although academic writing instructors generally prefer thesis statements to be written in the present tense.

5.5.2 Middle sections

The middle section contains body paragraphs that are designed to develop clear and cohesive lines of argument in support of the essay’s thesis. This is usually done by explaining the arguments in greater detail, providing several pieces of evidences, as well as an array of relevant examples that can help strengthen the validity of the arguments and improve the overall quality of the thesis.

The bulk of the middle section comprises ideas, concepts, and/or positions that are composed and derived from either primary (empirical) or secondary sources. This means that most of the academic reporting takes place in the middle section. We therefore expect verb tenses to be used logically and consistently throughout this section. Some examples of consistent (and inconsistent) use of verb tense in academic reporting can be found in Section 5.1, Table 2 and Section 1.2.2, Table 4.

The following subsections deal with the different parts of the middle section of a typical academic essay or research paper.

5.5.2.1 Literature review

Literature reviews are mostly expositions of relevant works/publications. For short essays, the literature review is typically part of the introduction section. For longer essays like theses and dissertations, there is almost always one entire section dedicated to it.

Citation styles like the APA recommend that the literature review section be written in the present simple or past simple tense.

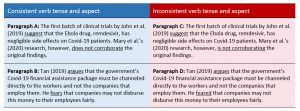

Referring to the comments on Pulido et al.’s (2020, pp. 378-379) excerpt in Table 4, Section 5.2.2, the choice of tense and aspect must be consistent throughout this part of your paper. What does “consistency” mean in this case? Let us take a look at the two sample paragraphs below.

Based on the above examples, the reporting verbs in Paragraphs A and B are consistent: suggest and does not corroborate are both in the present simple tense, and so are the verbs argues and fears. In these paragraphs, the reporting verbs exhibit parallel structure, i.e., they are grammatically aligned in terms of their tense and aspect marking.

Paragraphs C and D do not exhibit parallel structure. In Paragraph C, the reporting verb suggests is in the present simple tense, but is not corroborating is in the present continuous tense. Similarly, in Paragraph D, argues is in the present simple tense, but feared is in the past tense.

5.5.2.2 Methodology

For scientific or working research papers, the methodology is an important section. It is written in a mostly expository style, because the aim of the section is to explain how the study is carried out. In terms of verb tense usage, the methodology is written typically in the past simple or past perfect tense, since the process of designing the experiment, and collecting and analysing data would have already taken place in the time of writing.

5.5.2.3 Data analysis, findings, and evaluation

These sections present and evaluate the results of one’s research; hence, this subsection should ideally be written in either the present or past tense. For example:

Note that data analysis and presentation of findings tend to be written in the past tense, and evaluative statements in the present tense.

5.5.3 Conclusion

The final section, the conclusion, is similar to the introduction section in that a variety of verb tenses can be used by academic writers. This largely depends on their writing style. What is more crucial here is that academic writers should actively employ verbs that:

Summary