We now know that the warning that Sir Alexander Fleming gave during his Nobel Laureate speech in 1945, about Mr. and Mrs X’s self-medicating practices contributing to resistance of the bacteria with low dose penicillin, has indeed become a reality.

Over the past 70 years, we have created an antibiotic resistance issue that is described as a ‘crisis’ by the WHO, a ‘nightmare’ by the US CDC and a ‘catastrophic threat’ by UK’s Chief Medical Officer. Many studies have confirmed that there is a positive correlation between consumption of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance. The consumption of antibiotics depends on how people are able to obtain antibiotics. Some countries, like India and Spain, have permissive policies or poor regulation that allow antibiotics to be purchased over the counter in pharmacies. In Denmark, where they have more stringent policies, prescription given to patients by physicians is used with extreme caution and over-the counter purchases of antibiotics are impossible.

Individuals can misuse antibiotics by improper use of leftover medicines, not completing the full course of treatment and self medication. The inappropriate use of antibiotics has not only been seen in patients, as forewarned by Fleming, but also in health care professionals. Factors that contribute to health care professionals inadequately prescribing antibiotics may be related to how health care services are organized in different countries, including how health systems are financed, the number of doctors and pharmacies per inhabitant, the average time doctors spend with patients, and subsidy schemes for antibiotics. Studies in Europe have shown that antibiotic prescription rates are higher in countries with a greater number of physicians per inhabitant. Conversely, studies have shown that clinics that have fewer patient encounters tend to prescribe antibiotics less often, which might indicate that doctors who can spend more time with patients prescribe fewer antibiotics.

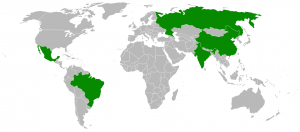

Between the years of 2000 and 2010, the global consumption of antibiotic drugs increased by 36%. Most of this increase (76%) occurred in the fast-growing economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, the so-called BRICS economies. In these countries, use of last resort drugs like cabapenems and polymixins has increased by 45% and 13% respectively.

Why is there such a difference on antibiotics usage around the globe? Isn’t there a ‘medical treatment ’ component to antibiotics that is based on scientific findings? Aren’t antibiotics medically required to hit a certain thresholds or achieve a standard best practice of use? How have there been so many variations of ways of obtaining it? Do the general public in some countries have more knowledge in medical practices than others? Where do these different views on antibiotics come from?

One reason for the difference in antibiotic use is because of the different opinions and traditions regarding how to treat infections. In addition, patients have a general misunderstanding that antibiotics are able to treat flu, colds, and coughs, which are mostly caused by viruses and generally only require rest and extra fluids. Chief Medical Officer of the UK, Dame Sally Davies explains “So we go off to doctors and ask for antibiotics, and we ask for them when they are not needed. Coughs and colds are viruses, they don’t respond to antibiotics. As doctors, we sometimes want to give patients what they want, other times, we will correctly prescribe an antibiotic, but not respond and change it quickly enough when the results come from the lab and say it’s resistant to that antibiotic you used”. Another challenge from the physicians’ standpoint, as mentioned by Dame Davies, is that it is difficult to tell if a patient has a viral or bacterial infection. The lab results to confirm this take too long to be clinically useful and most often are not done. By the time doctors receive a confirmed diagnosis, it is too late to treat the patient, or the patient has already improved. The fear of making a wrong diagnosis often encourages doctors to prescribe antibiotics just to be safe, an issue that is nicely highlighted in the documentary ‘Resistance’.

How do we deal with these complexities? Do we need better diagnostics? Do we need more sensitive tests? Do we need different types of antibiotics? What type of antibiotics are used for which conditions exactly?

In the field of medicine, antibiotics are used for two reasons: to treat a bacterial infection, and to prevent an infection in high-risk patients or during particular procedures. A doctor will prescribe antibiotics to treat a variety of different severe to moderately severe illnesses, such as acne (which would be unlikely to clear up without the use of antibiotics), skin infections, speeding up recovery of kidney conditions that carry risk of complications such as cellulitis or pneumonia. There are general groups of people that may be more vulnerable than others to infection, such as people who are above 75 years, infants, patients with diabetes or anyone who has a weakened immune system, such as HIV patients or patients on chemotherapy. Antibiotics are usually given as liquids, tablets or capsules. In more serious cases, injections or infusions of antibiotics can be given intravenously (directly into the blood or muscles). Serious bacterial infections include bacterial meningitis, septicemia (blood poisoning), infection of the outer layer of heart and infections inside the bone.

A physician would prescribe antibiotics for prophylactic reasons for things that have a known risk of infection that could lead to devastating effects upon infection. Examples would primarily be in surgeries, such as cataracts, glaucoma, join replacement, breast implants, pacemakers, removal of gall bladder and appendix or any transplant surgeries. Other examples would be if there is an animal or human bite, and if a cut or wound has come into contact with soil or faeces.

But antibiotics have to be used adequately, sparingly and cautiously. As Prof Antoine Andremont mentions, “Every time we take antibiotics, we are cured of course, but our own bacteria become resistant. This means there is a good side to antibiotics, the miraculous treatment. But there is also a downside, which means that each time, we opt for an antibiotic treatment, it has a certain impact on public health in general. That’s why antibiotics should only be used as and when required.”

In the next blog post, we will explore some of the challenges in tackling the global problem of antibiotic resistance and some of the possible solutions.