A post dedicated to familiarising ourselves with the very reason of existence of this blog – The common palm civet. Here are five interesting stories about the common palm civet that we would like to share with our readers.

- The tales of the palm civet’s multiple names.

Common palm civets are often referred to by a number of names. In the Malay language, it is known as the Musang, which also means weasel or fox. Other common names that the civets go by include, musang pandan and luwak.

In English, it is nicknamed ‘Toddy cat’ for its love of consuming the sap from palm trees, an ingredient for an alcoholic drink Toddy. People commonly think that civets are cats, but they actually have a closer relation to mongooses and hyenas.

Toddy alcoholic drink. Photograph by Kanchana Karunaratne (@ http://kanchana2015.blogspot.sg)

Its scientific name is Paradoxurus hermaphroditus, a Latin name with a very curious etymology. The species epithet ‘hermaphroditus’ is a result of confusion in sexing the animal, as both male and female have scent glands (AKA perineal glands) located under their tails, and yep you’ve guessed it, they resemble the testicles (Nelson, 2013).

- Sensing with scents.

Scents are important communication tools for the common palm civets, particularly so when it comes to territorial demarcation. Believe it or not, the common palm civets are able to discern the sex, species and familiarity of the scent’s owner, just by scent-markings alone (Nelson, 2013). The common palm civets leave behind self-identifying scents in the following methods:

- Dragging their scent glands against ground surfaces (longest-lasting)

- Rubbing their heels on walking surfaces

- Rubbing their ear-neck areas for surfaces above ground

- Urination

- Defecation

- Anal drag (done after defecation)

- What do civets eat?

The civet is omnivorous, eating a mixed diet of animals smaller than itself, molluscs, insects, leaves and a substantial diversity of fruits (we find out by sorting through their scat). They have teeth adapted to life as a fruit-eater (Nelson, 2013). And amazingly, the seeds actually remain mostly undamaged and are still able to germinate after passing through its digestive tract! Civets can be fantastic seed dispersers. This is especially so since they are not just confined to trees, and have been known to defecate and hence deposit seeds on the grounds of the forests, on the tree branches as well as in open areas created by fallen logs (Chakravarthy & Ratnam, 2015).

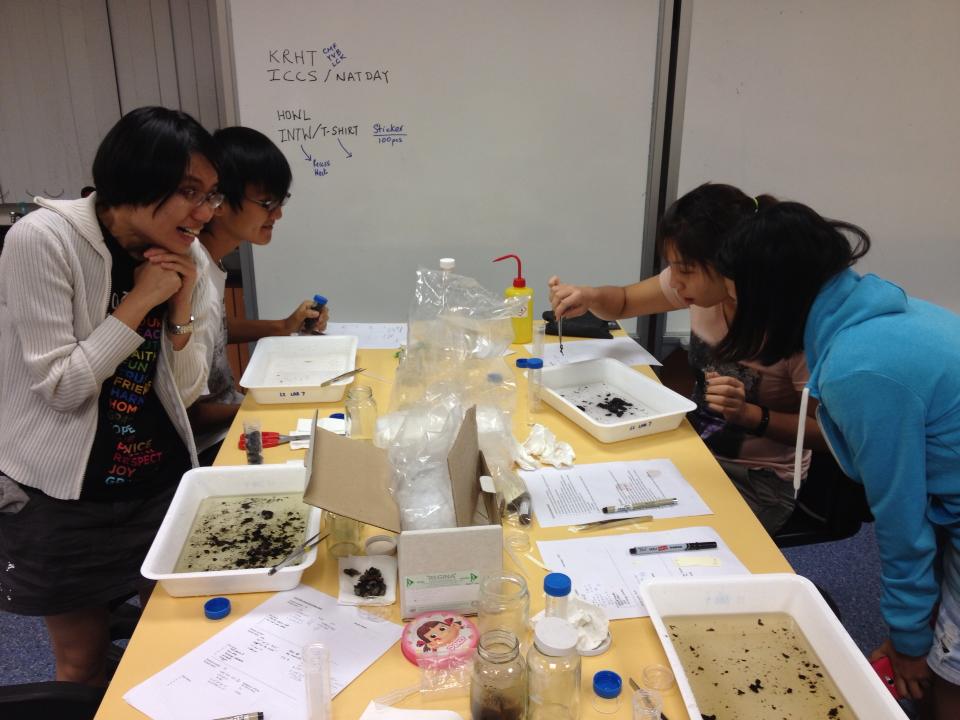

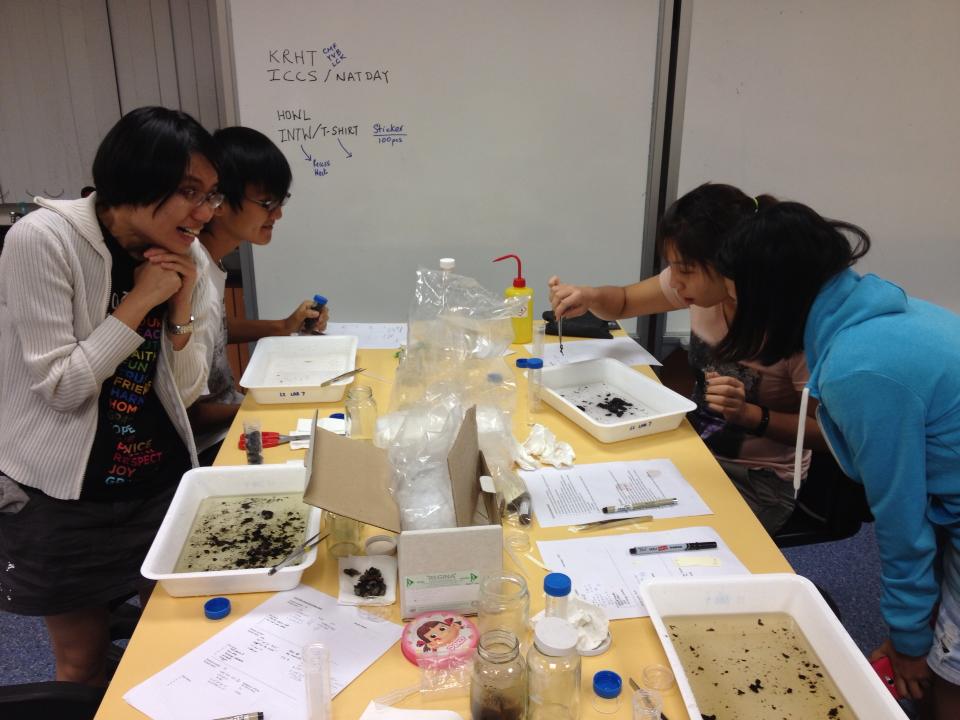

So… what did the civet eat? Sorting through the civet scat.

- How many babies do civets have?

Mummy civet with her 2 babies. Photograph taken by Chan Kwok Wai.

As solitary animals, the common palm civets track potential mates using scent-markings left by perineal glands. The scent-markings are indicative of the owner’s receptivity. Upon successful mating, the civet’s gestation period lasts an average of 60 days (Nelson, 2013). Each time, the mummy civets give birth to a litter of 2 to 5 babies, in nests usually located in tree hollows, crevices or other inconspicuous hiding spots. Young civets are taken care by their mothers for 3 months on average. Female civets take between 11 to 12 months to mature and be receptive to mating, while male civets take between 9 to 11 months. On average, civets have a lifespan of between 22 to 24 years (Tan, 2008).

A juvenile common palm civet caught on our night camera.

- Do common palm civets have SARS?? NOPE.

Anyone still remember the nightmare of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak back in 2003?

The common palm civet’s reputation was not spared too. Initial reports stated that masked palm civets (Paguma larvata) were found to have SARS-associated coronavirus. In a bid to contain the situation, there were plans to massacre 10,000 civets and even cull wild civet populations in China (Lovgren, 2003). However, later studies then found that the palm civets were not the source of SARS (Wang & Eaton, 2007). Instead, the host of the coronavirus was horseshoe bats and the inter-species transmission was due to the poor hygiene and cramped conditions in a live animal market (Lau et. al. 2005).

Those were some tough times for civets. The masked palm civet that was implicated in the SARS saga is a completely different species from Singapore’s common palm civet. There is no reason to associate the local palm civets with the episode of SARS, and there is certainly no need to worry about any common palm civet encounter in Singapore.

Masked palm civet (Paguma larvata) is also an asian civet, a completely different species from the common palm civets we have in Singapore. Photograph by Pete Oxford.

As Ria Tan (2008) from Wildsingapore puts it and I humbly quote: the SARS outbreak has shown us first-hand the dangers of human consumption of wildlife and closer interaction with wildlife as we encroach on and destroy wild habitats. The SARS episode, even long passed, is an extremely valuable lesson which highlights clearly to us the need to respect, as well as to protect nature.

References

Chakravarthy, D., & Ratnam, J. (2015). Seed dispersal of Vitex glabrata and Prunus ceylanica by Civets (Viverridae) in Pakke Tiger Reserve, north-east India: spatial patterns and post-dispersal seed fates. Tropical Conservation Science, 2(8), 491.

Lau, S.K., Woo, P.C., Li, K.S., Huang, Y., Tsoi, H.W., Wong, B.H., Wong, S.S., Leung, S.Y., Chan, K.H., and Yuen, K.Y. (2005). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 102(39):14040-14045.

Lovgren, S. (2003). SARS Scapegoat? China Slaughtering Civet Cats. Retrieved from http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/01/0109_040109_SARS.html

Nelson, J. (2013). Paradoxurus hermaphroditus. Retrieved May 23, 2015, from http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Paradoxurus_hermaphroditus/

Tan, R. (2008). Common palm civet. Retrieved May 23, 2016, from http://www.wildsingapore.com/wildfacts/vertebrates/mammals/hermaphroditus.htm

Wang, L. F., & Eaton, B. T. (2007). Bats, civets and the emergence of SARS. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_13

Photographs

“An adventures drink” by Kanchana Karunaratne. 10 September 2015. URL:http://wildpix.blogspot.sg/2011/04/common-palm-civet-of-siglap-estate.html

“A Mum with 2 kittens” by Chan Kwokwai. Flickr. 10 April 2011. URL:http://kanchana2015.blogspot.sg/2015/09/an-adventures-drink.html

“Masked palm civet (Paguma larvata)” by Pete Oxford. Widescreen Arkive. URL:http://www.arkive.org/masked-palm-civet/paguma-larvata/image-G114341.html