by Lee Kooi Cheng, Lee Gek Ling, & Lee Kit Mun

Introduction

Since AY15/16, it’s been our privilege to serve on the Centre’s Faculty Teaching Excellence Committee (FTEC). Three questions have preoccupied us:

- What constitutes good teaching?

- What are the indicators of good teaching?

- How do we effectively evidence teaching?

The answers to these questions provided a basis on which our evaluation work has been done. In particular, how our understanding grounded in related works has enhanced clarity in (a) expectations of how teaching is assessed; (b) indicators of teaching effectiveness; and to a certain extent (c) the direction in professional development initiatives at CELC that are aligned with that of the University.

In this blog post, while all the three questions are closely inter-related, we focus on our inquiry into evidencing teaching.

Background on Teaching Excellence Awards at CELC

Let’s begin with some background information on recognition of teaching excellence at CELC. Documentary evidence suggests that the CELC Commendation for Teaching Excellence was initiated in 1999. For nearly two decades, the primary criterion in capturing and identifying excellent teaching was through student feedback ratings. Teaching excellence was defined by a teacher having received the highest average student ratings for each of the categorized course types over two semesters. In addition to average student ratings, another consideration was response rate where a specific baseline percentage was identified for each course type.

In 2009, there was an exercise to re-look criteria for teaching excellence. Consultation sessions were held with other units within NUS, references drawn from their practices, background search was done to look at practices of other similar centres, and multiple discussion sessions were held with CELC colleagues. Inquiry then showed that research in assessing and evidencing teaching excellence especially in relation to the nature of work done at CELC was limited. Nonetheless, to better nuance and discern elements of excellence, the quantitative feedback ratings were calibrated to arrive at a weighted score. This calibration was done based on raw ratings, percentage of respondents, and number of students. Qualitative comments were considered, essentially to ascertain patterns showing indicators of teaching excellence.

Similar to earlier practice, nearly every year, there was only one award recipient for the CELC Commendation for Teaching Excellence for each course type. These recipients were then invited to submit their portfolios for CELC FTEC’s recommendation for the University’s Annual Teaching Excellence Award (ATEA).

In short, assessing teaching excellence is a complex exercise that is continually deliberated in pursuit of the most excellent way of assessing. Much effort has been put in by previous CELC FTEC teams to ensure that the recognition criteria are aligned with values of excellent teaching. Ours is an evolutionary step.

Following CELC’s recent direction to move towards a scholarly approach to our practices, we started our inquiry into assessing and evidencing teaching by addressing the major issue of using a single criterion (i.e., student feedback ratings) as evidence of teaching excellence.

Evidencing Teaching – What does the literature say?

While student feedback ratings remain a reliable, objective and valid indicator of teaching quality (Marsh, 2007), literature shows that there is consensus for evaluation of teaching to be informed by multiple sources (Carusetta, 2001; Chalmers and Hunt, 2016; Richardson, 2005; Salter, 2013; Seldin, 1998; Theall, 2010; Trigwell, 2001). Besides student feedback ratings, other sources include peer reviews on teaching/learning materials and classroom teaching, reflective or self-assessment exercise, and a critical analysis of one’s teaching effectiveness as a reflection of one’s articulated teaching philosophy. As aptly put by Theall (2010, p. 90), there is “no ‘one way’ to carry out valid and reliable evaluation (on teaching)”.

We further argue that the use of a single criterion as evidence of teaching excellence to make the short list of potential award winners, does not contribute meaningfully to an appreciation of what entails good teaching or expected standard. We agree that it is an important piece of evidence with useful information, but it contributes to only one perspective (namely the students’) which is further limited to only a few questions that are surveyed.

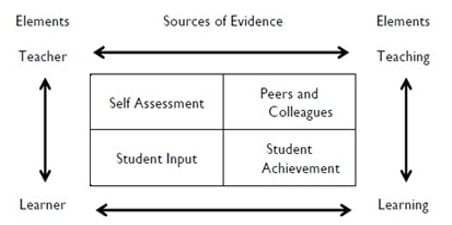

We draw from Chalmers and Hunt’s (2016) four quadrants of evidence (see Figure 1) as basis. This is further informed by other scholars (Biggs, 1999, 2014; Centra, 2000; Hattie & Donahue, 2016; Shulman, 1993; Theall, 2010; Trigwell, 2001).

Figure 1. Sources of evidence.

Chalmers and Hunt (2016) postulate that evaluation of university teaching should be a reflective exercise, informed by evidence drawn from student feedback ratings, student performance, feedback from colleagues on curriculum and classroom teaching, and self-reflection. These four aspects constitute Chalmers and Hunt’s (2016) four sources of evidence.

Student feedback on teaching, quantitative and qualitative, is an important source of evidence. However, although it does describe the students’ experience of the course, it is not the only indicator of teaching quality (Chalmers & Hunt, 2016; Theall, 2010; Trigwell, 2011) as it “does not measure learning” (Theall, 2011, p. 87). The student feedback instrument therefore must be thought through carefully in eliciting information that meaningfully evidences teaching effectiveness. In particular, students should not be asked questions that they are not equipped to answer such as pedagogical or content knowledge issues. Instead, students could provide feedback on how involved they were and how effective the instructional approaches were in the learning process (Centra, 2000). Specific indicators shared by Trigwell (2001) include clarity of presentation, teacher availability to students, and innovative approaches.

In terms of student achievement, among artefacts demonstrating this are reports on how students have progressed, graduate employment data, attainment of graduate attributes, grades, and learning analytics (Chalmers & Hunt, 2016). In the past few decades, “teaching effectiveness began to be viewed in terms of learning outcomes as well as pedagogy and instructional behaviours” (Theall, 2010, p. 90). This is aligned with Trigwell’s (2011) argument that there has been a body of research showing that there is a positive association between good teaching and high quality student learning, and that this can be documented. This is also in line with Shulman’s (1987) view that the evidence of student achievement could be inferred from their articulation of their learning, for example, whether they learned what they wanted to learn.

While there have been criticisms against it, peer review serves as another source of evidence. Chalmers and Hunt (2016) acknowledge that peer review exercises can be contentious and misconstrued as a form of monitoring. Centra (2000) argues that peer review by a single rater “can be biased or prejudicial” (p. 89). Chalmers and Hunt (2016) are persuasive in their assertion that a basket of criteria should be used to evidence teaching quality. Thus by inference, while peer review which is a good source of evidence may not provide comprehensive information, if it can be systematically done based on pedagogical underpinnings, it could form an integral part of either formative or summative appraisal. According to Chalmers and Hunt (2016), even the peer review exercise is multi-dimensional. It is more than classroom observation; instead, it also includes a review of one’s curriculum, module materials, teaching and learning approaches, assessment, and others. This resonates with Shulman’s concept of making one’s scholarship and work “public and susceptible to critique” (Shulman, 1998, p.13). For a more objective assessment, Centra (2000) suggests peer review be implemented by a 3 to 6-member committee who will assess the teaching portfolios or self-reports. We think that classroom observation can also be made more objective if conducted by internal and external reviewers, which is the current practice at CELC.

“Self-assessment” refers to individual teacher’s critical reflection on their teaching, its impact on student learning, and how the reflection might inform their future classroom/pedagogical practices (Chalmers & Hunt, 2016). Critical reflection is, in fact, necessary for us to learn from mistakes and to progress professionally as teachers whose ultimate goal is to transform minds by what is learned and how it is learned (Shulman, 1987). Self-assessment is a scholarly exercise that can be facilitated through a teaching portfolio (Chalmers & Hunt, 2016; Trigwell, 2001). Centra (2000) takes an opposing viewpoint about self-assessments. He mentions studies that have shown that “self-evaluations are not a meaningful measure of teaching effectiveness” (p. 89) in general. However, he acknowledges that teaching portfolios that include reflections about instructional decisions, thereby capturing the rationale and thinking behind those decisions, might well be strong evidence of useful self-assessment.

Evidencing Teaching at CELC

Based on our review of frameworks assessing and evidencing teaching, in AY17/18 with support from the CELC Management, there has been a major shift, conceptual and procedural, in which the CELC Teaching Excellence Award (CELC TEA) recipients are assessed. In terms of procedure, instead of the CELC Management identifying award recipients based on student feedback ratings, staff members who have student feedback ratings at or above the department average could submit their applications for the CELC TEA in the form of a 5-page teaching portfolio. Those further short listed to be nominated to the university level (ATEA) are then invited to submit a longer 15 page teaching portfolio, for which we not only write a report supporting our nomination, but we also peer review to ensure if needed that any claims made and evidence presented are aligned or clearly written up. Asking for the 5-page portfolio is consistent with that of the University’s Annual Teaching Excellence Award (ATEA), which requires applicants to submit a 15-page teaching portfolio to the University Teaching Excellence Committee. At the time of writing, there is some talk at higher levels that the page number be decreased and the procedure for ATEA further simplified. When that happens, CELC-TEA will keep apace.

Regardless of the logistical requirements mentioned above, conceptually, the ownership of (self) assessing, documenting, and showcasing teaching excellence is transferred to individual staff members. This is, in fact, in line with CELC’s encouragement to faculty members to prepare a teaching portfolio that documents teaching philosophy and impact of teaching on student learning.

Conclusion

Whilst teaching has been acknowledged as a pillar of excellence in university education, what teaching excellence is composed of, or how it may be objectively articulated and evidenced, has been more nebulous, not just in general, but even with reference to particular disciplines or subjects, our own English language teaching arguably even more so than others. In this blog, we have shared our findings in our inquiry focusing on evidencing teaching holistically through an informed and informative teaching portfolio.

The next step involves identifying standards and criteria, as well as specifying indicators of teaching effectiveness relevant to our field of English Language Teaching. Beyond this, these teaching standards in the broader context of professional development initiatives at CELC that are aligned with that of the University’s Educator Track, we think, should also be addressed.

We hope to continue to share our work on this platform. Meanwhile, we eagerly invite your response.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge CELC Management for encouraging us all to be scholarly and reflective teachers, and their support of our endeavours to be such.

References

Biggs, J. (1999). What the student does: teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research and Development, 18(1), 57–75.

Biggs, J. (2014) Constructive alignment in university teaching. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 1, 5-11.

Carusetta, E. (2001). Evaluating teaching through teaching awards. New Directions for Teaching and

Learning, 88, 31-40.

Centra, J.A. (2000). Evaluating the teaching portfolio: A role for colleagues. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 83, 87-93.

Chalmers, D., & Hunt, L. (2016). Evaluation of teaching. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 3, 25-55.

Hattie, J. A. C., & Donahue, G. M. (2016). Learning strategies: A synthesis and conceptual model. NPJ Science of Learning, 1, 16013. DOI:10.1038/npjscilearn.2016.13

Marsh, H. W. (2007). Students’ evaluations of university teaching: Dimensionality, reliability, validity, potential biases, and usefulness. In R. P. Perry & J. C. Smart (Eds.), The scholarship of teaching and learning in higher education: An evidence-based perspective (pp. 319-383). New York: Springer.

Richardson, J. T. E. (2005). Instruments for obtaining student feedback: A review of the literature, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(4), 387-415, DOI: 10.1080/02602930500099193

Salter, D.J. (2013). Cases on Quality Teaching Practices in Higher Education. Information Science Reference (IGI Global).

Seldin, P. (1988). Evaluating college teaching. In R.E. Young and K.E. Eble (eds.). College Teaching and Learning: Preparing for new commitments, pp 47-56. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform, Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1-23.

Shulman, L. S. (1993). Teaching as community property: Putting an end to pedagogical solitude. Change, 25(6), 6-7.

Theall, M. (2010). Evaluating teaching: From reliability to accountability. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 123, 85-95.

Trigwell, K. (2001). Judging university teaching. International Journal for Academic Development, 6(1), 65-73. DOI:10.1080/13601440110033698

Thank you for your work in enhancing the teaching award nomination process by making it more inclusive, and more importantly, by locating professional accountability at the level of the individual faculty — a laudable and positive first step toward counterbalancing the absence of the academic from higher education policy (Sabri, 2010). On your point that “those further short listed… are then invited to submit a longer… portfolio, for which we not only write a report supporting our nomination, but we also peer review to ensure if needed that any claims made and evidence presented are aligned or clearly written up”, I understand from the background that developmental feedback is also provided to those who were not shortlisted, and this is great. Better still if there is a local (departmental) platform for applicants to seek consultative advice on portfolio preparation and readiness pre-submission. Devolution of responsibility, be it in the workplace or classroom, is a sexy idea no doubt; a critical question to stimulate further work is what support structures are put in place to maximize the equality of opportunity.

Reference

Sabri, D. (2010). Absence of the academic from higher education policy. Journal of Education Policy, 25(2), 191-205.