Identification of individual Amur leopard cats possible using face and ventral patterns

The Amur leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis euptilurus) is the largest leopard cat. Unlike most leopard cats with bold black spots on a tawny background, their spot pattern is rather dim. Some researchers have said is it difficult or impossible to discern the patterns and individual from camera trap images. Until now.

A new research paper from South Korea has demonstrated that it is possible to identify individual Amur leopard cats using their face and ventral patterns.

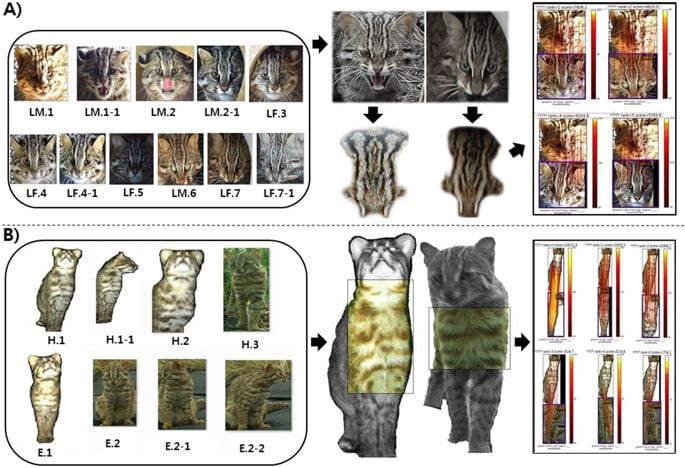

Comparison of markings from Amur leopard cat A) face from high-resolution images and B) vent from low-resolution camera trap images from Park et al. (2019).

The researchers used high and low resolution camera trap images and the image comparison software HotSpotter to reliably identify leopard cats baited using valerian scent lures.

I too found that face and ventral markings are practical for individual leopard cat identification, and they can be a lot less confusing than the sea of spots on the flanks. Of course, sometimes more data and angles is best. This seems promising for the Amur leopard cat, and I am looking forward to seeing population density estimates using the application of this method.

Park H., Lim A., Choi T-Y., Baek S-Y., Song E-G., Park Y.C. 2019. Where to spot: individual identification of leopard cats (Prionailurus bengalensis euptiluris) in South Korea. Journal of Ecology and Environment 43: 39. doi:10.1186/s41610-019-0138-z