Article: Japanese firms find profits in going green (https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/11/13/national/japanese-firms-find-profits-in-going-green/#.W4ifT5P7SR)

Summary

The article explores the financial benefits of investing in “green” products and technologies, by citing examples of two companies.

Kirishima Shuzo Co. cut costs of outsourcing its disposal of industrial waste, by investing in a recycling facility that harnesses waste methane from a fermentation process of its shochu (distilled sake) to, firstly, power its production, and secondly, generate excess electricity to sell to Kyushu Electric Power Co. for profit.

New Tech Shinsei Inc. has expanded its scope of operations, and started utilizing waste wood from forest thinning (which is unsuitable for furniture production (Mokulock, n.d.)) to create wooden toy blocks (called Mokulock) as an alternative to plastic ones.

Choosing to Go Green

In both cases, the Japanese veer towards “greener” ways: generating renewable energy in the former; changing product inputs from un-renewable electronics to biodegradable waste (wood) while reducing waste from forest thinning in the latter. To the layman, this may incidentally appeal to the Japanese’ claim to love nature. Hence, Japan’s apparently quaint, and spurious love for green could be reinforced.

How is “going green” represented?

However, it’s evident that the key focus of the article is not the environmental benefits of “going green”, but the financial benefits.

For both examples, there is repeated emphasis on cost and profit; Kirishima Shuzo Co. reduced disposal costs from 10,000¥ per ton to below 1,500¥ per ton. Its representative cited the financial soundness of this strategy: investment costs would be recovered as prices of renewable energy stay fixed for 20 years under the FIT system – a governmental policy which encourages renewable electricity production in private firms in Japan, by obligating electric power companies to purchase the energy on a fixed price, fixed period contract (IEA – Japan, 2018). New Tech Shinsei created Mokulock to stay afloat when its original business was failing.

Honestly it wasn’t for the environment at first, but rather for [them] to survive…

There is little analysis of how the “green” practices would benefit the environment. For example, there is no mention of how much wood from forest thinning is saved due to the Mokulock project, or how the sustainable disposal of waste by Kirishima Shuzo Co. will reduce its carbon footprint, apart from a vague mention that it would “help combat global warming”.

Thus, Japanese firms are represented as having a pragmatic approach to conservation, implying that their “going green” is motivated solely by financial interest. The environmental impact is almost portrayed as a side bonus. Strikingly, New Tech Shinsei’s representative stated: “Honestly it wasn’t for the environment at first, but rather for [them] to survive.”

The Japan Times is owned by Nifco, an industrial manufacturer. Its lack of affiliation with environmental organisations could explain the limited emphasis on environmental benefit. Instead, emphasising profits may be a conscious decision to appeal to the elite Japanese’ (part of its audience) practical relationship with nature.

Afterthoughts

Japanese’ attitude toward nature has been unique. For example, they see bonsai, an unnatural form of a live plant, as ‘love for nature’. This ambivalent view on nature innate in japanese culture (Asquith & Kalland, 1997), could have romanticized the article’s content in the eyes of its Japanese writers – they are unaware of its pragmatic implications to outsiders, which could damage the carefully constructed idea of Japan’s ‘innate love of nature’.

The pragmatic attitude towards environmental conservation is reflective of Japan’s historical relationship with nature. Historically, there have been regulations on preserving vegetation, which were justified by how it is necessary for maintaining the people’s needs – an anthropocentric approach. One example is an ancient court order on protecting “vegetation on the mountains” in order to “[secure] water” (Totman, 1989). This suggests that the Japanese have been consistent in conserving the environment for their own needs. Today, apart from keeping resources plentiful, “going green” is also used for reducing costs and increasing profits.

Also interestingly, what was described in this article could be a twist on ‘political ecology’ – political circumstances forcing environmental degradation (Stott and Sullivan, 2000), now that circumstances seem to promote conservation.

The bigger picture

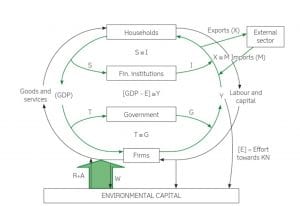

In both cases, human intervention was imperative to “going green” – government policies in the former, and creative entrepreneurship for the latter. The ultimate driving force is, however, still economic. Therefore, if economics discourse could recognize nature as a finite source/sink of resources, conventional economic forces which used to exploit nature could instead drive conservation. The FIT system may be a sign of politics moving in this direction.

Caption: A proposed concept including ‘environment capital’ as a source/sink among the pre-established web of economic flows (Thampapillai & Sinden, 2013).

Like this, the environment would be better understood by the layman as part of a closed loop with finite resources, to be exploited only sustainably.

(774 words)

References

Asquith, P. J., & Kalland, A. (1997). Japan’s Perception of Nature. Japanese images of nature: Cultural perspectives. (pp 21) Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press.

IEA – Japan. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.iea.org/policiesandmeasures/pams/japan/name-30660-en.php

Mokulock (n.d.) How did Mokulock come to be? Retrieved from https://mokulock.biz/

Stott, P. A., & Sullivan, S. (2000). Political ecology: Science, myth and power. London: Arnold.

Thampapillai, D. J., & Sinden, J. A. (2013). Environmental economics: Concepts, methods, and policies (Second ed.). South Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press.

Totman, C.D. (1989) The Green Archipelago: Forestry in Preindustrial Japan. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

All uncited pictures taken from the creative commons.