Hi everyone, welcome back to the last instalment on SG Fresh Produce. I’ll be moving into a case study of sorts next week. As mentioned previously, this post will be about the limitations of the SG Fresh Produce scheme.

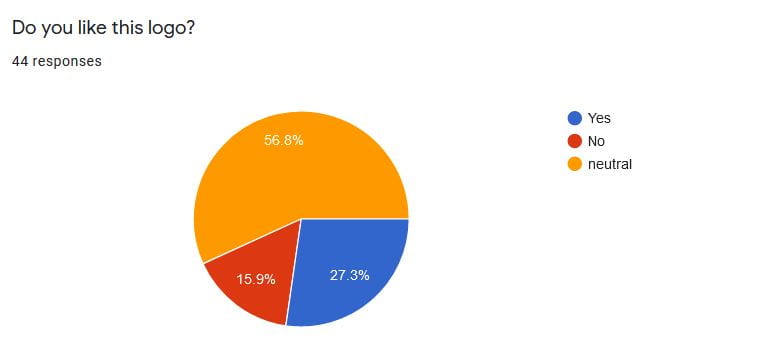

Starting off with the SGFP logo, not everyone liked it as much as I did.

The bulk of respondents were actually rather indifferent. I probably should have followed up asking if people will find this logo effective

The bulk of respondents were actually rather indifferent. I probably should have followed up asking if people will find this logo effective

Many people who did not like the logo disliked that the focus was on the “SG” component rather than on the freshness or that it was specifically farmed in Singapore. As mention in the previous post, I suspect this may have something to do with the overall SG Branding. I wonder if the target audience is not just the local population, but also customers to markets we export to. We do export some livestock to countries as far as Australia and the US. The relevant agencies would, of course, try their best to improve the perception of local products in the global market, including that of primary produce. Personally, I don’t think this interferes too much with the logo’s main aim to raise help shoppers to identify local produce. With the big “SG”, I doubt anyone would be mistaking it for imported produce anytime soon.

Another limitation of the SG Fresh Produce scheme is that it only applies to primary produce. This limits us to uncooked, unprocessed food.

The bulk of my respondents do not personally use primary produce on a weekly basis.

Just think back to the pre-COVID days, most of us patronised canteens/other cooked food stalls for lunch instead of bringing food from home (and of course there were those of us who did not need to worry about buying groceries as the government so kindly looked after these needs for two years). In fact, approximately a quarter of Singaporeans eat out daily.

But how can cooked meals be certified as being more locally produced? We certainly cannot have a fully locally produced meal – we don’t grow most of our carbohydrates to start with. In fact, the varied origin of our food has already been noted during the debate on the Geographical Indication Act (2014).

“For Katong laksa to qualify… the laksa leaf would have to be a Katong laksa leaf, the rice flour (used) would have to come from rice grown in Katong and the taupok (soya bean puff) would have to come from the soya bean that was grown in Katong. The clams would have to be harvested there as well”

– Ms Indranee Rajah, then Senior Minister of State for Law

Perhaps a separate certification scheme could be in place for cooked food that just looks at the origin of vegetables and proteins used. After all, there are already some F&B outlets that market themselves as being more conscious in terms of using local produce.

Of course, for the certification scheme to be successful, there must be demand for F&B outlets using local produce. Just slightly over 10% of respondents indicated that this would have any bearing on whether they supported a store. The main reasons for supporting would be taste – which may be tied to freshness – and price.

In the end, we are a rather practical bunch. In the end, we do prioritise convenience and price if taste is taken out of the equation.

Locally grown food will not be able to compete solely by virtue of having been grown in Singapore and would need to prove itself in terms of taste or price.

Join me next week where Mr James Kwan, Chief Marketting Officer of Barramundi Asia, shares his insights on some of the success and challenges they have faced so far.

Cheers,

Ee Kin

Recent Comments