Name of article: Gov’t approves JR Tokai plan to build maglev line

Link: http://www.japantoday.com/category/national/view/govt-approves-jr-tokai-plan-to-build-maglev-line

This article from the online newspaper, Japan Today, reports that the Japanese government has just approved the construction of an ultra-fast train using the magnetic levitation technology from Tokyo to Nagoya, despite environmental concerns.

The train will reach a top speed of more than 500 km/hour, cutting the travel time with one hour to being just 40 minutes. Construction will be undertaken in early 2015 by The Central Japan Railway Company (JR Tokai) and is expected to be complete in 2027 and cost 5.5 trillion yen, equal to 64.3 billion Singapore dollars.

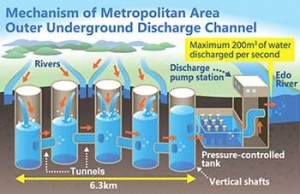

The article tells that the plan has been praised by the government for its expected massive benefits on economy, connectivity and tourism for cities along the route. However it also mentions that concerns have been raised on the environmental impacts from the construction and the long-term operational effects. As nearly 90 per cent of the 286-kilometer travel distance will be through tunnels there will be a lot of surplus soil from the excavations, and the article both refers to the transport minister and the Environment Ministry worrying about this issue, and the environment ministry furthermore asking JR Tokai for more info on the project’s impact on groundwater running down from the mountains.

It is noteworthy that the article really does not question how the project can be approved while even the public authorities have important unanswered questions on environmental impacts. And this article is actually among the only articles describing the approved plans, which elaborates on the environmental concerns. To me, this implies that the environmentally concerns are naturally subordinated to the economic concerns in this case, which we also found in some of the large construction cases involving nuclear plants and dams.

In other sources, some people have also raised concerns that once operational, the 286 km route with only four stops on the way will accelerate the concentration of the nation’s resources and activities in Tokyo. Having learned of the decreasing population and increasing urbanization and its implications for the rural areas as well as for the average Japanese’s relation to nature, one understands this concern.

Further readings and reference points:

- Information from JR Tokai on the project: http://english.jr-central.co.jp/company/others/_pdf/otherinformation-82.pdf

- Article by Tetsu Okazaki in The Japan News: http://the-japan-news.com/news/article/0001652218

- Editorial in The Asahi Shimbun: http://ajw.asahi.com/article/views/editorial/AJ201410180020