Although air pollution is a major global issue that affects 9 out of 10 people while reaching a death toll of 7 million annually, it is more than just a health risk that we need to address. Rather, its disproportionate impacts highlight the lack of environmental justice. Unfortunately, low income and marginalized communities often bear the brunt of air pollution due to their lack of ability or capacity to mitigate the consequences.

This blog thus explores the link between environmental (in)justice and environmental concerns pertaining to the rising levels of air pollution worldwide, which entails an urgent call to action.

Environmental justice refers to fair treatment and distribution of environmental benefits and burdens, including the right to breathe clean air among all communities. It also encapsulates the meaningful involvement of all people regardless of their background, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

The burden of air pollution tends to fall greatly on poorer, more socially deprived communities. Fig 2 shows the spread of PM2.5 pollution across the globe, whereby it is evident that higher concentrations of the particulate matter are observed in less developed or developing regions including Asia and Africa. At least 92% of the population in these continents are exposed to air quality levels that pose a significant risk to their health.

Fig 1: Uneven concentration of PM2.5 across the world (Source: State of Global Air Report)

This phenomenon is not only noted globally, but can also be seen within a specific country. For instance, a study conducted in Hong Kong found that low-income households are likely to be exposed to higher mean PM2.5 levels, particularly in the suburban northwest region of the country where population densities are the highest.

Similarly, low income families are also exposed to higher levels of air pollution compared to wealthier individuals in the United States. This can be attributed to a lack of emissions regulations and enforcement, disproportionate placement of pollution sources nearby low-income neighborhoods, and the excessive political power of large emitters. One example of a major source of pollution is vehicular emissions along the I-710 freeway in Los Angeles. 70% of the 1 million people residing near the highway belong to minority or underprivileged communities, and are thus disproportionately impacted by the air pollution from transportation and industrial activities daily.

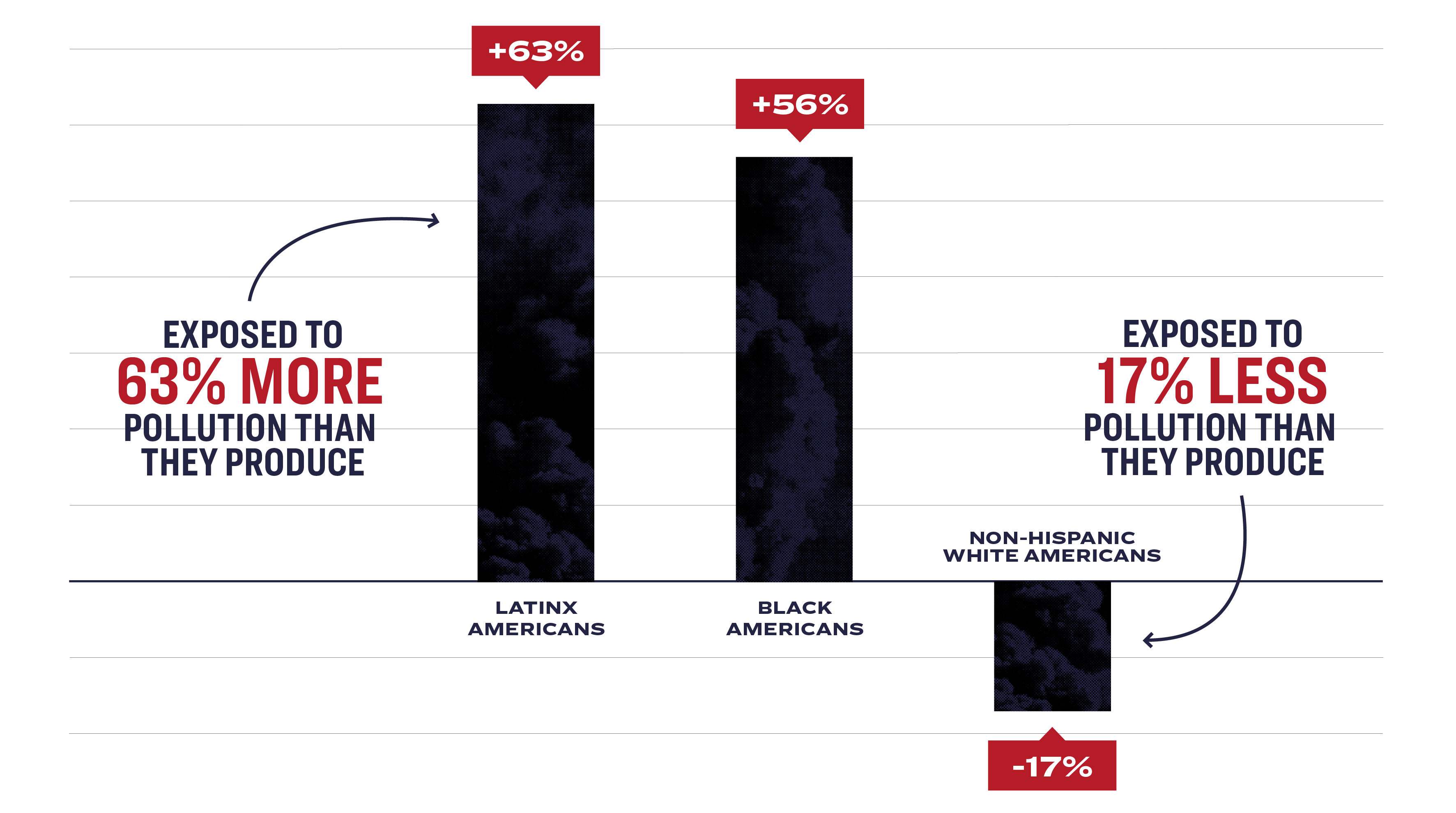

People of colour also suffer significantly from the implications of poor air quality. In a study examining racial–ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure in the US, the researchers concluded that pollution inequity exists because PM2.5 exposure is disproportionately caused by the consumption of goods and services mainly by the non-Hispanic white majority, but excessively inhaled by black and Hispanic minorities. Fig 2 illustrates the extent of the injustice faced between the various communities.

Fig 2: People of colour are largely affected by air pollution not caused by their actions (Source: Tessum et al., 2019)

According to a report on Environmental Justice and Refinery Pollution, 13 refineries across the United States had released elevated levels of benzene into residential neighbourhoods where 57% of the population are people of colour and 43% live below the poverty line. Benzene is dangerous because it contributes to various forms of leukemia that suppress the formation of healthy blood cells, weaken immune systems, and increase susceptibility to other diseases.

Fig 3: Stupp Corp., a steel pipe manufacturing company, located in suburban Louisiana (Source: Sok, 2019)

Such disparities stem from the hegemonic ideologies that federal governments impose on certain neighbourhoods. These regions were marked as “risky” due to the high population of Blacks living there. Black neighbourhoods were generally associated with higher crime rates, thus decreasing their real estate value and leaving them “ideal” for industrial development and properties.

These marginalized groups of people not only constantly breathe in bad air, they also face a lack of means to seek treatment for the health impacts or adopt measures to cope with the pollution. They have less access to healthcare facilities as well as limited knowledge and information about the health effects of air pollution. Their positionalities and identities thus put them at a disadvantage when it comes to gaining equal access to life opportunities and achieving an ideal standard of living.

To conclude, the link between air pollution and environmental justice is a complex matter that affects millions of people worldwide. The unequal distribution of the consequences of pollution underscores the need to address the root causes of such unfairness. Governments should provide more assistance and financial aid to marginalized and socially deprived communities, while including them in the formulation of environmental laws and policies. The rights of these people must be protected and improved to enhance sustainability in the long term.

Bibliography

CCAC and UNEP. (2019). Air Pollution in Asia and the Pacific: Science-based solutions. New York: Asia Pacific Clean Air Partnership.

Houston, D., Wu, J., Ong, P., & Winer, A. (2004). STRUCTURAL DISPARITIES OF URBAN TRAFFIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA: IMPLICATIONS FOR VEHICLE-RELATED AIR POLLUTION EXPOSURE IN MINORITY AND HIGH-POVERTY NEIGHBORHOODS. Journal of Urban Affairs, 26(5): 565–592.

Kunstman, B., Schaeffer, E., & Shaykevich, A. (2021). Environmental Justice and Refinery Pollution. Chicago: Environmental Integrity Project.

Li, V. O., Han, Y., Lam, J. C., Zhu, Y., & Bacon-Shone, J. (2018). Air pollution and environmental injustice: Are the socially deprived exposed to more PM2.5 pollution in Hong Kong? Environmental Science & Policy, 80: 53-61.

Mohai, P., Pellow, D., & Roberts, J. T. (2009). Environmental Justice. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 34: 405-430.

Quillian, L., & Pager, D. (2001). Black Neighbors, Higher Crime? The Role of Racial Stereotypes in Evaluations of Neighbourhood Crime. AJS, 107(3): 717-767.

Tessuma, C. W., Apte, J. S., Goodkind, A. L., Muller, N. Z., Mullins, K. A., Paolellaa, D. A., . . . Hill, J. D. (2019). Inequity in consumption of goods and services adds to racial–ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure. PNAS, 116(13): 6001-6006.

WHO. (2018, May 2). 9 out of 10 people worldwide breathe polluted air, but more countries are taking action. Retrieved from World Health Organization: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-05-2018-9-out-of-10-people-worldwide-breathe-polluted-air-but-more-countries-are-taking-action

Leave a Reply