Scented products, which include items such as perfumes, deodorants, candles and air fresheners, are widely used to create an aesthetically pleasing environment by masking unwanted odours. However, the chemicals used in these products have been associated with adverse effects on air quality and health. They are a primary source of indoor air pollution, but they also contribute to air pollution outdoors due to their increased usage. This blog explains how and why some of our favourite products might be contributing to the pollution problem.

A single fragrance in a product can contain a mixture of hundreds of chemicals, such as limonene, which gives off a citrus scent. Some of these chemicals react with ozone in ambient air to form toxic secondary pollutants like formaldehyde. Perfumes contain a mixture of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), including alcohol, aldehydes, and synthetic fragrances which are released into the air each time the product is applied. Research shows that the average number of VOCs emitted was 17, and each product emits up to 8 hazardous chemicals. VOCs are known to have a negative impact on air quality as they contribute to ground-level ozone and particulate matter, which can also lead to respiratory illnesses.

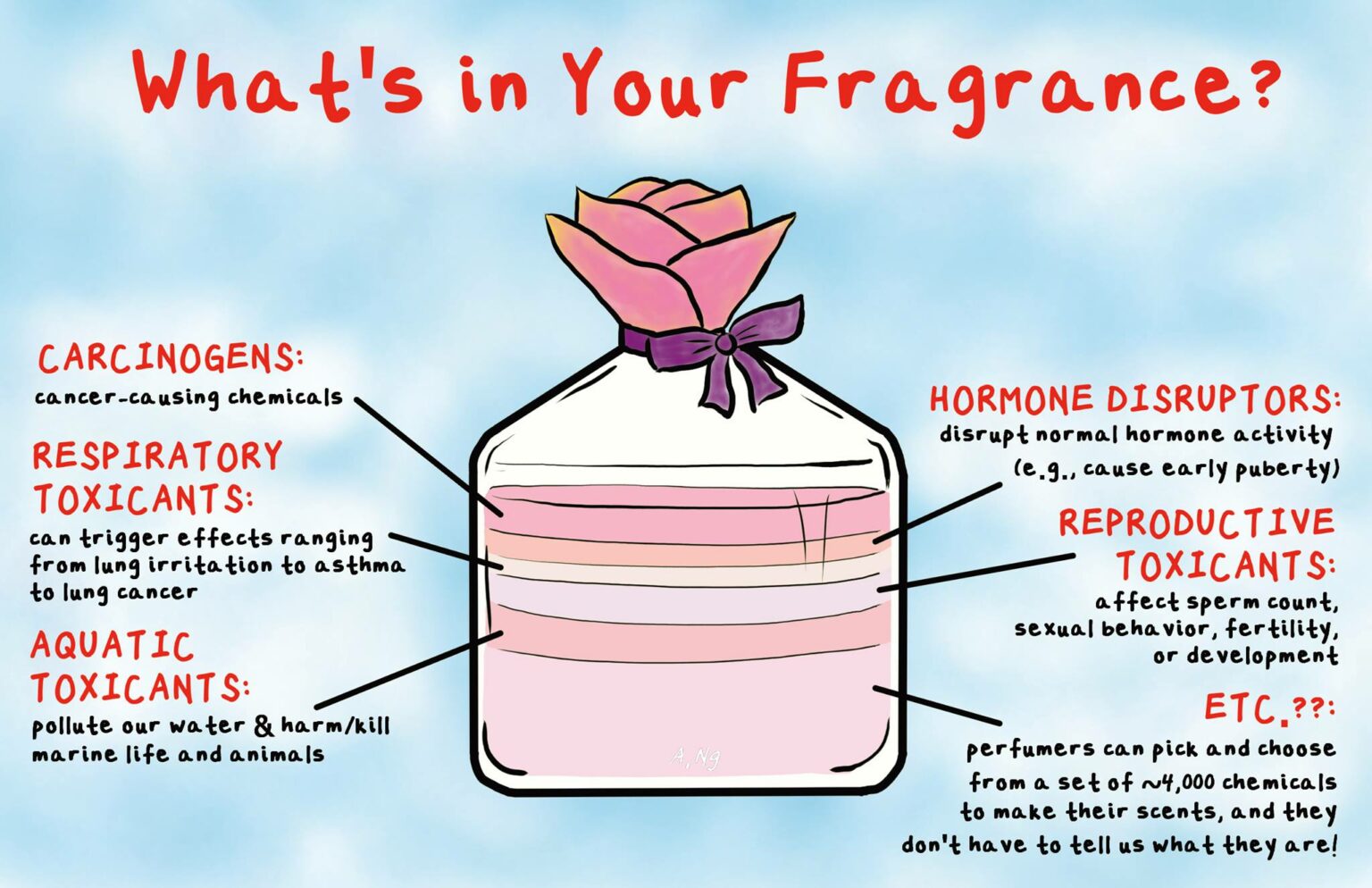

Fig 1: Some of the harmful impacts caused by scented products (Source: Safe Cosmetics, 2023)

Wearing deodorants or perfumes, or even burning scented candles can be the biggest source of indoor air pollution. Studies show that the number of VOCs in the air increases with more people being within a confined space. The levels of many compounds were found to be 10 to 20 times higher indoors than outdoors, especially without access to proper ventilation. Even with a ventilation system installed, the problem only gets transferred outdoors (literally) as the chemicals are dispelled outside, raising overall air pollution levels.

The Covid-19 pandemic saw a rise in the usage of disinfectants and sanitizers globally. The chemicals in cleaning products are extremely harmful to the environment, although their effects are largely invisible to the human eye. A study led by the University of Saskatchewan posited that hydrogen peroxide-based disinfectants created indoor air pollution far above acceptable standards. After mopping floors with 0.88% hydrogen peroxide solutions, airborne hydrogen peroxide levels shot over 600 ppb, a value 600 times higher than fresh air levels.

Fig 2: Cleaning products (Source: Dalli, 2019)

Moreover, “long-lasting scents” are the result of innumerable microcapsules adhering to clothing, bursting with every movement and rubbing of the fabric. Consumers are unknowingly inhaling these artificial, and toxic, chemical substances. Children are increasingly exposed to these synthesized chemicals, which may cause symptoms like headaches, dizziness and impairment of cognitive abilities.

Although these scented products do provide benefits on a personal level, more needs to be done with regard to increasing awareness of their negative implications and taking action to limit scent pollution. For example, producers and consumers should move towards products that contain more natural and organic ingredients or switch to fragrance-free products instead.

Bibliography

Behal, A., & Behal, D. (2020, December 3). Smell good, breathe bad: How scented products add to air pollution. Retrieved from Down To Earth: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/environment/smell-good-breathe-bad-how-scented-products-add-to-air-pollution-74501

NOAA. (2018, February 15). Those scented products you love? NOAA study finds they can cause air pollution. Retrieved from National Oceanic and Atmopsheric Administration: https://www.noaa.gov/news/those-scented-products-you-love-noaa-study-finds-they-can-cause-air-pollution#:~:text=The%20chemical%20vapors%2C%20known%20as,fine%20particulates%20in%20the%20air.

Reiko, M. (2021, July 30). The Sweet Danger of Scent Pollution. Retrieved from Nippon: https://www.nippon.com/en/in-depth/d00703/

Safe Cosmetics. (2023). Fragrance Disclosure. Retrieved from Campaign for Safe Cosmetics: https://www.safecosmetics.org/resources/health-science/fragrance-disclosure/

Steinemann, A. (2021). The fragranced products phenomenon: air quality and health, science and policy. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 14: 235-243.

Steinemann, A. C., MacGregor, I. C., Gordon, S. M., Gallagher, L. G., Davis, A. L., Ribeiro, D. S., & Wallace, L. A. (2011). Fragranced consumer products: Chemicals emitted, ingredients unlisted. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 31(3): 328-333.

Zhou, S., Liu, Z., Wang, Z., Young, C. J., Trevor, C., VandenBoer, B., . . . Kahan, T. F. (2020). Hydrogen Peroxide Emission and Fate Indoors during Non-bleach Cleaning: A Chamber and Modeling Study. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(24): 15643–15651.

Leave a Reply