In this issue, we turn the spotlight on blended learning: what it is, why educators could consider adopting this approach to improve student learning, and how they can go about doing so. We are also pleased to feature NUS students who have participated in blended modules. They share their experiences and perceptions of participating in such modules, including the learning benefits they enjoyed and from their perspectives, the improvements that can be made for future iterations of blended modules.

What is blended learning?

Garrison and Vaughn (2008) describe blended learning as the “organic integration of thoughtfully selected and complementary face-to-face and online” teaching approaches (p. 148). It goes beyond simply layering on numerous online or face-to-face learning activities to an existing module without considering their impact on student engagement and the course objectives. When judiciously carried out, it combines face-to-face oral and online written communication such that students are fully engaged and the module objectives are fulfilled in ways that are not possible if either learning modes were taught individually (Vaughn, Cleveland-Innes, & Garrison, 2013). In short, blended learning draws benefits from the affordances of online and face-to-face learning for optimised learning.

Why adopt blended learning?

Blended learning, when applied thoughtfully and with intent, can lead to improved student learning in several ways (Stein & Graham, 2014):

| Improved instructional design

Blended learning modules tend to be more intentionally designed than their face-to-face counterparts and may also involve instructional designers and educational technologists in the design process. |

Individualised learning opportunities

Using digital materials (which students can access and review on-demand based on their individual needs) and automated assessments (which provide students with immediate and corrective feedback that directs them to revisit course materials). |

| Increased guidance and triggers

In a blended module, the course environment provides a clear path through all aspects of the syllabus (resources, activities, and assessments), with students receiving explicit guidance at every step. |

Increased engagement through social interaction

Blended modules offer opportunities to incorporate online class discussions and collaborations which can increase student-to-student interaction in a way which may not be possible in a purely face-to-face course. |

| Easier access to learning activities

Learning activities could be made available online and students can engage with the activities at their own schedule and pace. |

Time on task

It might be more visible in a blended module because it would be easier to track student activity in an online environment. |

Blended learning and flipped classrooms: Are they the same?

A common question many educators ask is whether blended learning and the flipped classroom approach are the same, or not. According to Braeme (2013), flipping the classroom is an approach where “students gain first exposure to new materials outside of class, usually via reading or lecture videos, and then using class time to do the harder work of assimilating that knowledge… through problem-solving, discussions, or debates.” In other words, a flipped classroom module would have students doing lower-order cognitive work (gaining knowledge and comprehension) outside classroom time, while during classroom time, they would be doing higher-order cognitive work (application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation).

A flipped classroom would be considered a blended learning module if the combination of classroom and online activities displays a “fundamental rethinking of course design to optimise student engagement” (Garrison & Vaughn, 2008). In short, flipped classroom modules can be considered blended learning modules if they fulfill the criteria for what constitutes blended learning.

Blended learning in NUS: How many blended modules has the University offered so far?

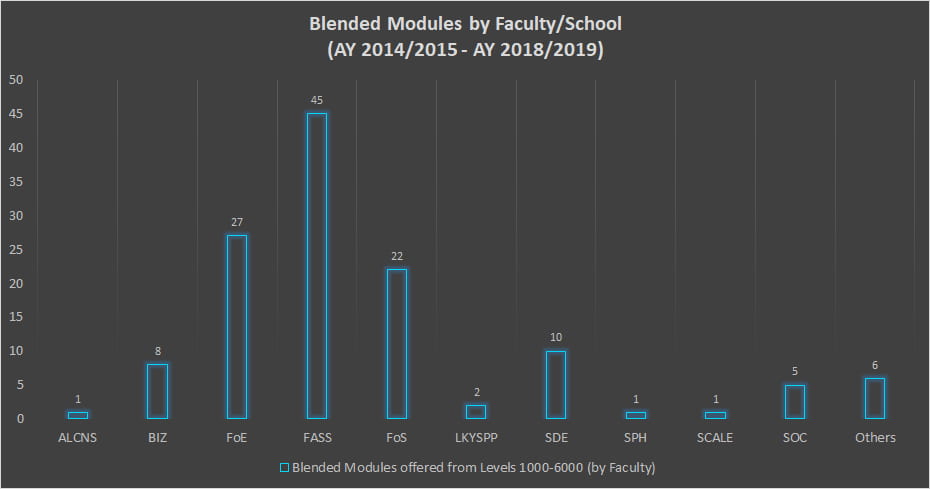

NUS has offered blended modules since Semester 2 of AY 2013/2014. Based on information provided by the Office of the Senior Deputy President and Provost, and the Registrar’s Office at NUS, the Faculties and Schools which offer blended modules over the last five academic years (AY2014/15–AY2018/19) are reflected in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Blended modules offered at NUS over 5 academic years (AY2014/2015 – AY2018/2019), by Faculty/School. (Sources: Office of Senior Deputy President & Provost, Registrar’s Office, NUS)

The trend in the last 5 years indicates that since AY 2014/2015, most Faculties and Schools offer blended modules at all levels, including Levels 5000 and 6000. The Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS) offers the highest number of blended modules (45 blended modules), followed by the Faculty of Engineering (FOE, 27 blended modules) and Faculty of Science (FOS, 22 blended modules).

Student Sharing

Since blended learning modules were introduced in NUS in AY 2013/2014, what have the experiences and perceptions been for students? In the students’ view, did the blended/flipped approach make a difference in the way they learnt compared to the conventional approach? What aspects of the blended approach in these modules could be improved further to optimise the teaching and learning experience? What can we, teachers, learn from our students’ experience?

For students who took CM2101 “Physical Chemistry 2”, their positive response to the strategies employed during the blended tutorials for this module was consistent with some of the pedagogical benefits cited by Stein and Graham (2014) of the blended approach, compared to fully online or fully face-to-face classes:

Active learning activities, leading to increased student engagement

“They are much more effective than normal tutorials. Actually, normal tutorials aren’t necessary because most students go there just looking for the answers to problems, which can be uploaded to [the content management system] IVLE directly. Active learning tutorials are different, we go there not knowing what to expect and the lessons are much more engaging.”

“They are much more effective than normal tutorials. Actually, normal tutorials aren’t necessary because most students go there just looking for the answers to problems, which can be uploaded to [the content management system] IVLE directly. Active learning tutorials are different, we go there not knowing what to expect and the lessons are much more engaging.”

Group discussions with increased guidance and triggers

“I wished they were longer because we tend to only solve one question. But I must say the depth of discussion and mode of discussion coupled with your attentive feedback and encouragement really boosts self confidence in the topic and reinforces concepts much better…First time I was exposed to this style and actually really felt I was learning.”

“I wished they were longer because we tend to only solve one question. But I must say the depth of discussion and mode of discussion coupled with your attentive feedback and encouragement really boosts self confidence in the topic and reinforces concepts much better…First time I was exposed to this style and actually really felt I was learning.”

Online lectures, which enable easier access to learning activities and individualised learning opportunities

“I learn more from online lectures because I get to rewind and review things that I have missed out or have difficulties understanding. I can learn at my own pace which is great.”

“I learn more from online lectures because I get to rewind and review things that I have missed out or have difficulties understanding. I can learn at my own pace which is great.”

“I think online lectures should be conducted in the future as well, as it accommodates students with different learning speeds.”

The students also suggested ways of improving some of the strategies used in the blended module, in this case, the online video lectures:

Provide enhanced triggers and guidance within the online videos

“A problem with online lecture is that there is lack of interaction between lecturer and students. Hence, quite often I felt watching the online lecture is like watching TV, which may end up being sort of lack of focus. Hence, I suggest there some highlight or screen-writing working could be done to highlight the focus and important sections.”

“A problem with online lecture is that there is lack of interaction between lecturer and students. Hence, quite often I felt watching the online lecture is like watching TV, which may end up being sort of lack of focus. Hence, I suggest there some highlight or screen-writing working could be done to highlight the focus and important sections.”

“Online lectures worked well for the theory based chapters (e.g., Rotational, Vibrational). But not for chapters that require visualization (e.g., Group Theory I and II). It would be good if these chapters can be conducted in class using ball and stick models to demonstrate the symmetry elements and operations. It would be a great help.”

Engaging students in blended learning: How do I get started?

If you’re keen to incorporate blended learning in your practice and require support or funding, you can do the following:

Attend the blended learning course offered by CDTL

Attend the blended learning course offered by CDTL

CDTL offers a course which guides you through an evidence-based approach towards designing and developing a module for blended learning.

![]() Apply for the LIF-T Grant for blended modules

Apply for the LIF-T Grant for blended modules

Colleagues who are keen to develop new blended modules or redesign existing modules to improve teaching and learning using tech-enhanced pedagogies and learning strategies can consider submitting an application for this grant.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to the following colleagues for their support and contributions to this article:

- Office of Senior Deputy President & Provost, and the Registrar’s Office, NUS, for the information on blended modules, and

- Assoc Prof Adrian Lee (Chemistry/FOS) for the anonymous student feedback from his blended/flipped module.

- The instructors for CDTL’s blended learning course – Assoc Prof Adrian Lee, Mr Alan Soong, and Ms Jeanette Choy – for the constructive input provided.

References

Brame, C., (2013). Flipping the classroom. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved from http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/flipping-the-classroom/.

Garrison, D. R. & Vaughan, N. D. (2008). Blended learning in higher education: Framework, principles, and guidelines (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Stein, J., and C. R. Graham (2014) Essentials for blended learning: A standards-based guide. New York: Routledge.

Vaughan, N., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Garrison, R. (2013). Teaching in blended learning environments: Creating and sustaining communities of inquiry. Athabasca, Canada: AU Press