Hello friends! I have always been fascinated by how the dogs (Canis lupis familaris) are subspecies from wolves (Canis lupus)! A great way to imagine I am hugging a wolf will be hugging a Siberian Husky, a breed of Canis lupis familaris, but there’s a big difference between the two. The main difference between these two canids is that Canis lupis familaris underwent the domestication process, where Canis lupus was the first species to be domesticated by humans due to their positive socialization (Anderson, 2018). Socialization is a process for a maturing animal to learn and interact with humans.

Let us find out the differences between these categories together!

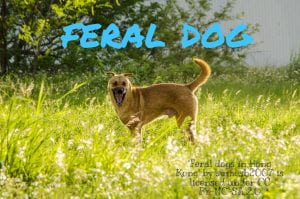

Assign options A,B and C to the picture you think suits best:

A. Domestic dog

B. Free-ranging domestic dog

C. Feral dog

“Feral dogs in Hong Kong” by sumesh2007 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Here are the answers!

Stray dogs which are going to be fed by humans

Stray dogs which are going to be fed by humans

Was it hard to differentiate between feral and free-ranging domestic dogs (FRDD)? It was confusing to me before I studied it. Some of the feral dogs do look like FRDD, like these feral dogs in Palestine.

“Feral dogs in Palestine” by بدارين is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

In Singapore, we commonly term the FRDDs as “stray/street dogs’’. The FRDDs can be owned or unowned: The unowned FRDDs are free to roam around, typically living close to human homes and are not controlled by humans (Anderson, 2018). The FRDDs can find food and shelter intentionally or non-intentionally provided by humans. Also, FRDDs can be owned dogs, meaning the owners allow them to roam around on various times of the day without supervision (Coppinger & Coppinger, 2001).

Similarly, feral dogs have gone through the domestication process. The main distinguishing factor of feral dogs from FRDD is that feral dogs avoid humans and have no socialization. They live away from humans without food and shelter support. However, feral dogs are not considered wild animals as have gone through domestication and have the genetic composition for domesticated dogs (Ádám Miklósi, 2015).

Despite the evolution of dogs from wolves, these two candids are finding their way back together via hybridization in recent years. It is of environmental concern as the hybridization of FRDD and wolves can change the genetic integrity of the wolves, which could potentially threaten the fitness of wolves. It was reported that 6 wolf-dog hybrids were found in Estonia and 2 wolf-dog hybrids were found in Latvia (Kadzidlowo Hindrikson, Ma¨nnil, Ozolins, Krzywinski, Saarma, 2012). A wolf-dog hybrid of male polish spaniel (FRDD, abandoned or free roaming) and female gray wolf (wild animal) was found in Poland, at Wildlife Park (Kadzidlowo Hindrikson et al., 2012).

“First-generation (F1) wolf-dog hybrid from Wildlife Park Kadzidlowo, Poland” by Andrzej Krzywinski is licensed under CC BY 3.0

“First-generation (F1) wolf-dog hybrid from Wildlife Park Kadzidlowo, Poland” by Andrzej Krzywinski is licensed under CC BY 3.0

To conserve the wolf population, wolf hunting should be discouraged and prohibited to prevent the lowering of wolf numbers. With smaller wolf populations, the impacts on hybridization between FRDDs and wolves are amplified, threatening the conservation of wolves, especially if the fitness of subsequent wolf offspring are affected (Kadzidlowo Hindrikson et al., 2012).

I’ll probably get to hug a hybrid wolf soon… Hopefully not since it would mean the wolf species are threatened.

Paws out!

References:

Anderson, E. N. (2018). The first domestication: How wolves and humans coevolved. By Raymond Pierotti and Brandy R. Fogg. 2017. Yale University Press, New Haven. 326 pp. Ethnobiology Letters, 9(2), 247-249. doi:10.14237/ebl.9.2.2018.1379

Coppinger, R., Coppinger, L. (2001). Dogs: a new understanding of canine origin, behavior and evolution. Chicago University Press, Chicago, IL.

Hindrikson, M., Ma¨nnil, P., Ozolins, J., Krzywinski, A., Saarma, U. (2012). Bucking the Trend in Wolf-Dog Hybridization: First Evidence from Europe of Hybridization between Female Dogs and Male Wolves. PLoS ONE 7(10): e46465. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046465

Miklósi, A. (2015;2014;). Dog behaviour, evolution, and cognition (Second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199646661.001.0001