St. John’s Island and Lazarus Island are two of Singapore’s southern islands. In the past, majority of the inhabitants were Malays and it had been so until the residents of the islands moved out into the main island of Singapore. However, how did these islands with a largely Malay population ended up with English names? At the same time, when searching about these islands, we often come across their Malay names – Pulau Sekijang Bendera and Pulau Sekijang Pelepah. To find out the origins of the names, we dug through some historical archives, looked at old maps and consulted islanders who used to live on the islands.

Before Sir Stamford Raffles arrived in this part of the world, Singapore and its surrounding islands, including St. John’s and Lazarus, were inhabited by Orang Lauts (sea people) coming from both the Riau Islands of Indonesia and Malaysia (Wurtzburg, 1945). These Orang Lauts (or ‘sea people’ whose lives were intimately tied to the sea) were likely to be followers of the Temenggong (chief of security) of the Johor-Riau Empire who settled on the Singapore mainland in the 1800s and depended on the Orang Lauts not only for fishing but also to make the surrounding waters safer for the trade that was already going on in the region then (Trocki, 2007). According to one of our interviewees, Cikgu Jalil, these locals referred to St. John’s Island as Pulau Sekijang Besar while Lazarus Island was called Pulau Sekijang Kechil . These names were perhaps used before the quarantine stations were built on the islands. Surprisingly, not too long ago, we came across a news article that used this old name in their report on the asbestos case on St. John’s Island and other neighbouring islets.

Sekijang is a combination of two Malay words – seekor and kijang. Seekor translates to ‘one’ while kijang means ‘deer’, hence consolidated into sekijang which means ‘a deer’. However, we do not know what kind of deer they were. It could have been a (1) mouse deer, which is still commonly found in Singapore’s main island or (2) roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), a Eurasian deer brought over by the British or (3) barking deer, native to Singapore and found widely in Southeast Asia in the 1800s.

The legend of deer appearing on the islands was passed from generation to generation by the islanders and residents of neighbouring islands. Berita Minggu wrote a feature article on ‘Asal usul nama pulau-pulau di selatan’ (The origin of the names of the Southern Islands) (Berita Minggu, 30 August 1981). In the article, Encik Jaafar bin Hussein, former penghulu (headman) of one of the islands, told the reporter a story of two deer on the islands. Both deer initially inhabited one of the islands. However, one day they split up and one stayed on Pulau Sekijang Bendera while the other went to Pulau Sekijang Pelepah, so now both islands had one deer each. Thus the islands are called ‘sekijang’ meaning ‘one deer’. Of course, one should take legends with a pinch of salt. After all, legends rarely have solid evidence and the older generations who can ascertain their truth have long passed away.

However, while is it impossible to now say for certain about the deer which used to be on the islands, thus putting into question the provenance of the Sekijang name, on 16 January 1906, the Straits Times reported Captain Stockley and Lieutenant Baring going down to St. John’s Island to shoot a buck which the government then put on St. John’s Island a few months prior. Apparently, the buck had become vicious and was thus culled.

Were the British were trying to recreate the myth of the islands as heard from the local population? Or were they intending to make the island a game reserve by leaving the two deer there to breed? The latter is more likely the case since by this time, the British had already named the island St John’s Island which was arguably a bastardization of the word sekijang (see below). Nevertheless, deer seem to be a part of the narrative of the local naming of St. John’s and Lazarus.

Another name by which Pulau Sekijang Besar was known by the locals was Pulau Sekijang Bendera. This was brought about by the new functions for the island imposed in the 1800s by the British.

Bendera means ‘flag’ in Malay. Between 1873 and 1978, St. John’s Island was used as a Quarantine Station (Straits Times 14 August 1875). In order to notify the ships in its vicinity that there was a Quarantine Station in the area, yellow flags were flown from the station. These quarantine flags could have inspired the name Pulau Sekijang Bendera. In another interview with Mr. Sulih, he mentioned that there were flags on the water tanks too. With flags erected at so many different places, St. John’s Island has indeed earned its name ‘bendera’.

How did Pulau Sekijang Besar/Bendera end up with the name St. John’s then? There are various accounts regarding this.

Wurtzburg (1945) and Savage & Yeoh (2013: 332) referred to Crawfurd’s notes which suggested that ‘St. John’ is actually a corruption of the word sekijang when Sir Stamford Raffles came to Singapore in 1819. The story goes like this: when the British anchored off St. John’s Island on 28th January 1819, they asked the islanders the island’s name. They were told ‘sekijang’ which they misheard as ‘St. John’ and the name stuck. Cikgu Jalil, a former islander gave us another account on how ‘St. John’ was derived:

“… [When] Raffles came to Singapore, … he had two missionaries on his ship. Raffles was in search for water, and so Farquhar ordered the two missionaries to go on land to find water. These two individuals were St. John and Lazarus. When St. John went to the island of what we call today as St John’s Island, he did not find any water. However, when Lazarus went to the island beside it, he found a spring and brought back water… [When] they returned, Farquhar named the island according to their names, Lazarus and St. John. ”

But how accurate were these accounts? Was the name St. John’s really one derived from the first time Sir Stamford Raffles came to Singapore? As we dug into some old maps of Singapore and its surrounding island, we discovered that this might not be the case.

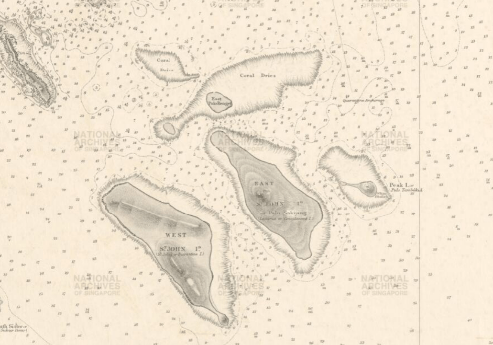

The map above is a highly detailed chart of the Straits of Malacca entitled ‘The South Part of the Straits of Malacca inscribed to Captain G.G. Richardson, by Captn. J. Lindsey’. Published at the end of the 18th century by Laurie and Whittle, this 1798 gem actually had St. John’s Island printed on it with the name ‘Isle of John’. This was more than 20 years before Raffles set foot on Singapore, so Raffles may not be the first to call the islands St. John. In fact, it could very well be that Sir Stamford Raffles and his entourage could have consulted these early maps and already picked up the name St. John even before they sailed into the region.

The veracity of Cikgu Jalil’s account is also put to question when we consider that while the early maps threw up the name St. John’s, the name ‘Lazarus’ only made its appearance on maps in the 1900s.

Before that, the islands were collectively known as St. John’s Islands and was differentiated by either ‘West’ and ‘East’ or ‘No. 1’ and ‘No. 2’.

More likely, Lazarus Island got its name from Lazarette (isolation hospital) which was built on the island during the years when St. John’s was used as a quarantine station. While the quarantine station was used to accommodate those that had been in contact with people inflicted with contagious diseases while on-board the ship, the Lazarette accommodated passengers with confirmed cases of the disease. The Lazarette consisted of “European and Native Ward, outhouse etc. and residence for medical subordinate in charge” (Straits Observer, 25 March 1875).

Before the name ‘Lazarus’ gained traction, Lazarus Island was known as Pulau Sekijang Pelepah, pelepah meaning ‘palm frond’. Whilst no one knew exactly when people started calling Lazarus Island Pulau Sekijang Pelepah, Cikgu Jalil recounted a story of how pelepah came about. According to him, there was once two Indonesians and one of them was named Ode La Kadim. Ode La Kadim was sitting under a tree when night began to fall and the tide rose. At high tide, he observed many coconut leaves falling and sinking into the sea. Inspired by this, he named the island Sekijang Pelepah.

Although we are not so sure if this story is true, we certainly did observe a few stands of coconut trees on the island.

In their book ‘Singapore street names: A study of toponymics’ Savage and Yeoh (2013) said that names, especially those that last for a very long time, gives identity and historical resonance to streets, buildings and areas. While our research has yet to give us a definitive answer on how St. John’s and Lazarus Island got their names, and chances are this may not even happen, these names remain special as they serve to remind us of the times when the St John’s and Lazarus Islands were used as a quarantine station and lazarette respectively. For former islanders, such as Cikgu Jalil, the islands are still referred to by their original names, Pulau Sekijang Bendera and Pulau Sekijang Pelepah; for them, these names are still salient nomenclatures with which they establish an emotional attachment to the islands. Sure, the provenance of these local names may be based on legends and therefore questionable. Nevertheless, they are an inheritance – our inheritance from those who inhabited Singapore and its surrounding islands before us – that is important for us to remember and take stock of even as we now refer to them as St John’s Island and Lazarus Island, derived more from our former British colonizers. After all, is that not what the Bicentennial Celebrations in Singapore is all about – to recuperate our past beyond the supposed founding of Singapore by Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819? Indeed, perhaps it is time now to call these two islands at the south of Singapore by their original names.

References:

Savage, V. R., & Yeoh, B. (2013). Singapore street names: A study of toponymics. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd.

Trocki, C. A. (2007). Prince of pirates: the Temenggongs and the development of Johor and Singapore, 1784-1885. NUS Press.

Wurtzburg, C. E. (1954). Raffles of the eastern isles. Hodder and Stoughton.

December 11, 2022 at 3:46 am

Chinese Ming Maritime maps named them as 官屿 ” official islet” which explains the official flag “bendera” in Pulau Sekijang Bendera.