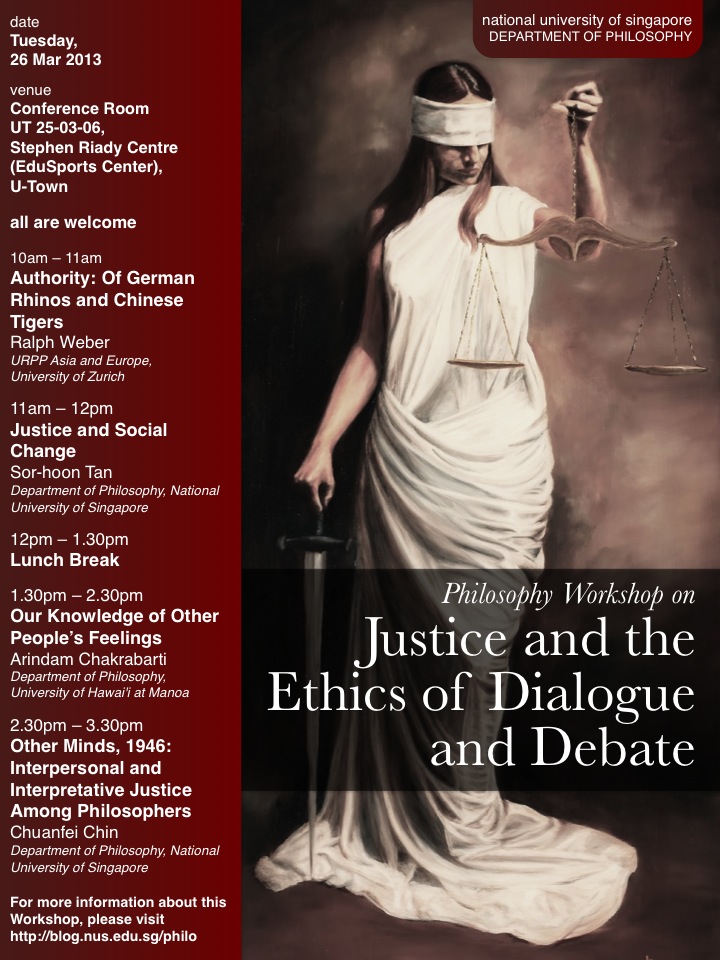

The Department of Philosophy will be holding a philosophy workshop on Justice and the Ethics of Dialogue and Debate.

Date: Tuesday, 26 March 2013

Time: 10am – 3.30pm

Venue: Conference Room UT-25-03-06, Stephen Riady Centre (EduSports Center), U-Town, NUS (Click here to view map)

The papers presented in this workshop investigate the topic of justice by combining both epistemic and ethico-political perspectives. While all papers draw on the writings of various philosophers (from Abhinavagupta and Dharmakirti to Peter Strawson, from Wittgenstein to Hanfeizi) and various philosophical traditions (e.g. the Marxist, Aristotelian and Confucian traditions), each paper does not simply end up with stating the Chinese vs. the Indian or vs. the Western view of justice, but each presents an argument about some or another aspect of justice that can philosophically stand on its own. Justice and the ethics of dialogue and debate will thus be related to aspects such as the problem of epistemic access to a second person’s inner, especially, emotional states, the question of social change with regard to what each member of the group owes the group and vice versa, and the complicated relation of epistemic and political authority.

Being a workshop, the event seeks to practice what it theorizes, and is open for everyone to participate in active dialogue and debate. Presented papers:

Authority: Of German Rhinos and Chinese Tigers

Ralph Weber, URPP Asia and Europe, University of Zurich (10am – 11am)

This paper inquires into authority, both in its epistemic and deontic forms. I particularly seek to expand on the Polish Dominican logician and philosopher J.M. Bocheński’s The Logic of Authority by raising objections against his way of linking it to freedom and autonomy as well as by including in my discussion additional, unheeded aspects of authority (the authority of office, the authority of number), some of which have been discussed earlier in Alexandre Kojève’s La Notion de l’Autorité. In the course of my argument, I shall discuss the famous Russell-Wittgenstein episode about the possibility of knowing whether or not there is a rhinoceros in the room and draw on Wittgenstein more generally for disentangling the relation between authority and autonomy. An episode in the Han Feizi 韓非子 on believing whether or not there is a tiger in the market leads me to the topic of moral and political authority and its dependence on epistemic authority (which often involves different persons or institutions, but, for example, in the Guanzi 管子is invested in one and the same person, that of the sage-ruler). My goal is to explore those instances of authority in which both epistemology and politics can be said to interrelate, merge, or clash.

Justice and Social Change

Sor-hoon Tan, Department of Philosophy, National University of Singapore (11am – 12pm)

What might we gain from a comparative study of Confucianism and some Western philosophy on the topic of Justice? Some scholars have questioned whether there is any concept of justice in early Confucianism. One response is to either identify the equivalent concept, or find elements in Confucian philosophy that could be reconstructed into a Confucian theory (or at least perspective) on justice. However, going beyond the assumption that justice problems are universal, and exploring the possibility that problems arising from “circumstances of justice” might be understood differently by Confucians in their social criticisms, allows us to tap into deeper differences in social ideals, conceptions of human beings and social relations, that will provide more radically critical perspectives with which to interrogate contemporary experience.

Lunch Break

(12pm – 1.30pm)

Our Knowledge of Other People’s Feelings

Arindam Chakrabarti, Department of Philosophy, University of Hawai’i at Manoa (1.30pm – 2.30pm)

Understanding the feelings of other people is not only a condition for caring social practice, and Buddhist altruistic compassion, it is the pre-condition for any successful dialogue, even philosophical dialogue, especially across cultural and linguistic barriers. Yet philosophers still do not know how we manage to do it. Neither perception nor inference seems capable of yielding knowledge of what another self—the second person—is currently experiencing, wanting, feeling, thinking. And whether at all another body is enlivened by a self, though not myself, remains hard to “prove”. In this paper, the intricate argumentation by Dharmakirti – the Sautrantika-Yogacara Buddhist philosopher – to prove by an inference that streams of consciousness other than one’s own exist will be examined, side by side with J.S. Mill’s version of the Argument from Analogy and its decisive refutation by P.F. Strawson. After a brief discussion of Max Scheler and Edith Stein’s views on sympathy and empathy, we turn to Kashmir Shaivist epistemology of imagining what it is like to be another self. Inspired by a detailed examination of Abhinavagupta’s insights on how we know, identify with and empathically feel other people’s feelings, the paper will propose assigning the work of knowledge of other selves to imagination, a means or faculty of knowing at least as powerful and indispensable as perception, inference and testimony.

Other Minds, 1946: Interpersonal and Interpretative Justice Among Philosophers

Chuanfei Chin, Department of Philosophy, National University of Singapore (2.30pm – 3.30pm)

A 1946 symposium on ‘Other Minds’ between John Wisdom, J.L. Austin and A.J. Ayer marked a shift in the analytic debate about our knowledge of other minds – from a sceptical orientation to a naturalist one. I focus on two aspects of their dialogue. First, both Wisdom and Austin argue that the traditional concern with other minds fails to account for the depth and difficulty of our interpersonal relations, particularly our access to others’ emotional states. This is partly because our epistemology is normally dependent on an ethics of trust and vulnerability. Second, Ayer’s response is remarkably rude. He misconstrues their arguments, then uses their conclusions. I use this interpretative injustice to clarify the very norms of interpersonal justice which Wisdom and Austin highlight. Then I assess how far naturalist assumptions are responsible for these insights and conflicts. I take the symposium to illustrate the challenge of philosophical dialogue – in this case, between a Wittgensteinian philosopher influenced by psychoanalysis, an ordinary language philosopher, and a post-positivist philosopher intent on solving the problem.

Alan Cole took his Ph.D. in Buddhist Studies at the University of Michigan, in 1994. Since then he has taught at a number of American colleges and universities, with most of those twenty years spent at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. His recently published books – Text as Father: Paternal Seductions in Early Mahayana Buddhist Literature (UCal Press, 2005) and Fathering Your Father: The Zen of Fabrication in Tang Buddhism (2009, UCal Press) — are concerned with understanding how narratives function within important Buddhist texts in India and China. As these titles suggest, he has been working to develop a theory about how Buddhist authors knowingly constructed their works and naturally this involves worrying about how intersubjectivity functions in these artful literary gambits. More recently, he has tried to extend these theoretical perspectives in a comparative work titled, “Fetishizing Tradition: Desire and Reinvention in Buddhist and Christian Narratives.” (The book is currently under review at SUNY Press.) He is currently working on another book, Patriarchs on Paper: A Critical History of Chan (Zen) Literature from 600-1200, (currently under review at UCal Press).

Alan Cole took his Ph.D. in Buddhist Studies at the University of Michigan, in 1994. Since then he has taught at a number of American colleges and universities, with most of those twenty years spent at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. His recently published books – Text as Father: Paternal Seductions in Early Mahayana Buddhist Literature (UCal Press, 2005) and Fathering Your Father: The Zen of Fabrication in Tang Buddhism (2009, UCal Press) — are concerned with understanding how narratives function within important Buddhist texts in India and China. As these titles suggest, he has been working to develop a theory about how Buddhist authors knowingly constructed their works and naturally this involves worrying about how intersubjectivity functions in these artful literary gambits. More recently, he has tried to extend these theoretical perspectives in a comparative work titled, “Fetishizing Tradition: Desire and Reinvention in Buddhist and Christian Narratives.” (The book is currently under review at SUNY Press.) He is currently working on another book, Patriarchs on Paper: A Critical History of Chan (Zen) Literature from 600-1200, (currently under review at UCal Press).