As consumers, we can take action against marine chemical pollution through the lifestyle choices and purchasing decisions we make. Purchasing non-toxic products not only reduces the amount of harmful chemicals that may eventually reach and contaminate the ocean but also ensures that human health is not affected during the product’s production and use stage. So, what are some common consumer products that may have toxic chemicals in them?

Sunscreen products

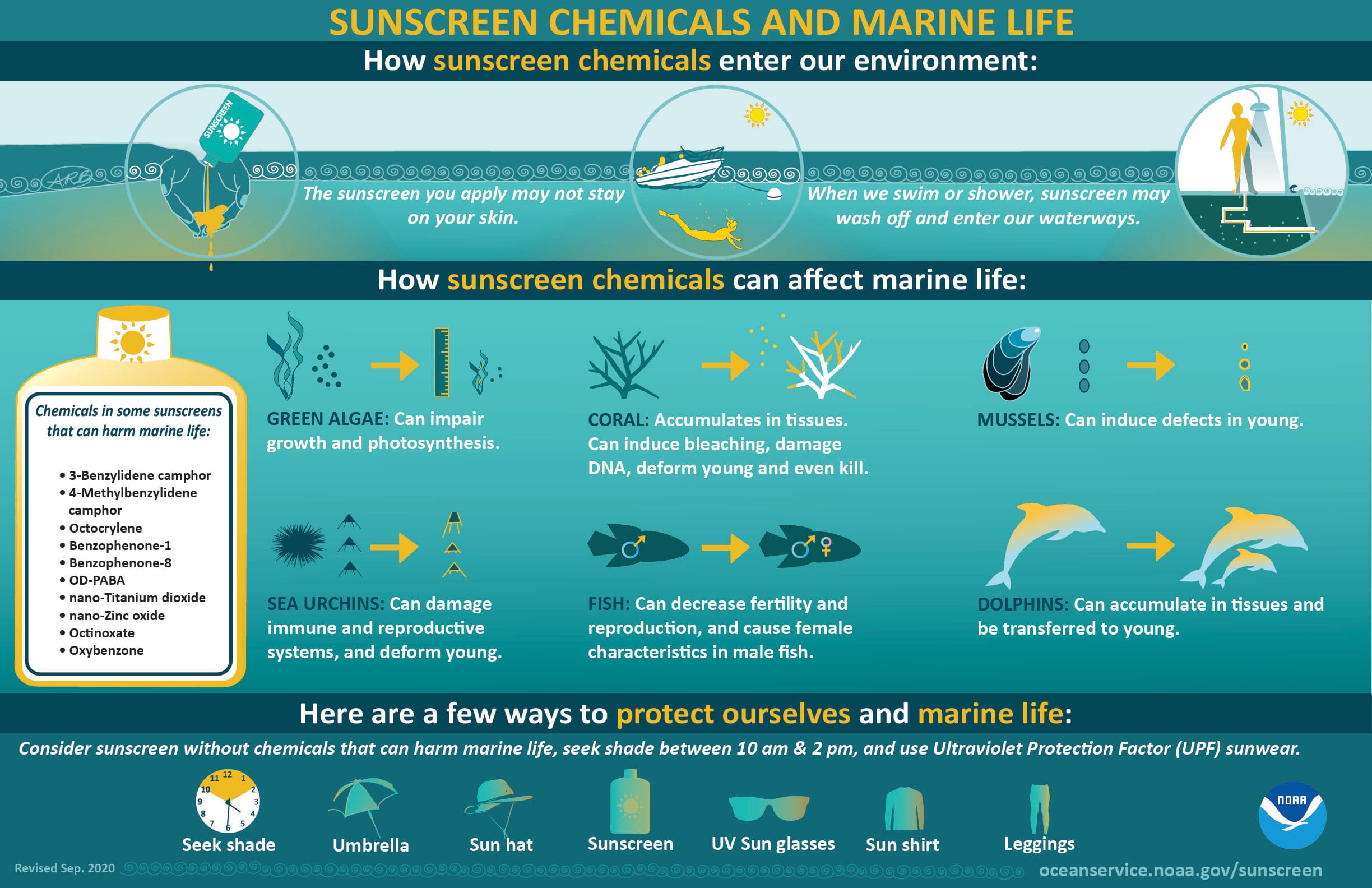

The effects of chemicals in sunscreen on the health of coral reefs have been widely publicised. Some studies have found that ultraviolet (UV) filters like oxybenzone and octinoxate increase corals’ susceptibility to bleaching, cause permanent DNA damage and disrupt growth (Downs et al., 2016; He et al., 2019). These chemicals may also have negative health impacts on other marine life, as shown in the figure below. Various destinations, including Hawaii and Thailand’s marine parks, have banned the use of sunscreens that contain some of these harmful chemicals. This has led to the development of reef-safe sunscreens that often use non-nano zinc oxide or titanium dioxide instead.

Infographic on sunscreen chemicals and marine life (NOAA, 2021)

However, not everyone is supportive of the ban on certain sunscreens. Michelle, the cosmetic chemist who runs Lab Muffin to educate others on the science behind beauty products, has posted a blog post and Youtube video explaining the issue. Her points contesting the ban are:

- The concentration of sunscreen chemicals in the environment is much lower than that in the studies conducted. Sunscreen chemicals are unlikely to be toxic in the environment when in such low amounts.

- There is not enough scientific evidence that sunscreen chemicals are causing harm to coral reefs.

- Many researchers think that the effect of sunscreen chemicals on coral reefs is minuscule, compared to other stressors like climate change.

I do agree with her point that focusing on sunscreen chemicals may be shifting attention away from bigger environmental issues. Governments should perhaps be spending this time and energy on decarbonisation instead. Nonetheless, I think that as consumers, we should still apply the precautionary principle and make the pre-emptive choice to reduce the possible negative environmental impacts we may be causing.

When looking for sun protection, one can opt to wear UV-protective clothing instead of applying sunscreen. Ultraviolet Protection Factor (UPF) is an indicator of the amount of UV radiation that can penetrate a fabric to reach your skin (Skin Cancer Foundation, 2019). It is recommended to wear clothing with a rating of at least UPF 30 for good protection. The next best option would be to use a reef-safe sunscreen that does not contain the ingredients mentioned in the infographic above. Make sure to check the ingredient list on the sunscreen, even if it has been labelled ‘reef-safe’ or ‘reef-friendly’ as the use of such claims is currently not regulated.

Other products

Apart from sunscreen, many other personal care products may also contain chemicals with adverse effects on marine organisms, such as parabens (Xue et al., 2015), triclosan (Dhillon et al., 2015) and synthetic musks (Wollenberger et al., 2003; Luckenbach et al., 2004). MarineSafe has published a list of chemicals of concern that you can refer to when purchasing products. But how are we expected to keep track of them all whenever we are purchasing products?

There are various apps that allow you to scan product barcodes to find out more about the chemicals present. Think Dirty is a popular app in North America that assesses the potential risks of personal care products based on their ingredients. While it does not specifically rate products based on their impact on the marine environment, it looks at scientific research to determine the carcinogenicity, as well as developmental and reproductive toxicity of ingredients, which can likely have impacts on marine organisms too.

Another app to look out for is Scan4Chem. The app was developed on the basis of the consumer’s right to know under the EU’s Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) regulation. Launched in some European countries, it allows suppliers to submit product information on the presence of substances of very high concern to the database, as well as consumers to request information from suppliers on products that are not yet on the database. The app covers consumer products that do not have ingredient lists, such as toys, clothing, furniture and electronics.

Such technological developments facilitate information sharing and improve transparency, allowing consumers to make informed decisions for both marine and human health. I hope this post has helped shed some light on practical ways you can choose non-toxic products and be a conscious consumer.

See you in the next post!

References

AskREACH (2019). Scan4Chem app for checking substances of very high concern in products launched. Retrieved from https://www.askreach.eu/scan4chem-app-for-checking-substances-of-very-high-concern-in-products-launched/ on 30 March 2022.

BBC (2021). Thailand bans coral-damaging sunscreens in marine parks. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-58092472 on 30 March 2022.

Carmichael, R. & Brown, J. (2022). The Invisible Wave: Getting to zero chemical pollution in the ocean. Back to Blue, Retrieved from https://backtoblueinitiative.com/marine-chemical-pollution-the-invisible-wave/ on 12 March 2022.

Center for Biological Diversity (2021). Hawai‘i Senate bill bans harmful sunscreen chemicals. Retrieved from https://biologicaldiversity.org/w/news/press-releases/hawaii-senate-bill-bans-harmful-sunscreen-chemicals-2021-03-09/#:~:text=HONOLULU%E2%80%94%20Sunscreens%20containing%20two%20harmful,banning%20oxybenzone%20and%20octinoxate%20sunscreens on 30 March 2022.

Dhillon, G.S., Kaur, S., Pulicharla, R., Brar, S.K., Cledon, M., Verma, M. & Surampalli, R.Y. (2015). Triclosan: Current status, occurrence, environmental risks and bioaccumulation potential. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(5): 5657-5684.

Downs, C.A., Kramarsky-Winter, E., Segal, R., Fauth, J., Knutson, S., Bronstein, O., Ciner, F.R., Jeger, R., Lichtenfeld, Y., Woodley, C.M., Pennington, P., Cadenas, K., Kushmaro, A. & Loya, Y. (2016). Toxicopathological effects of the sunscreen UV filter, oxybenzone (benzophenone-3), on coral planulae and cultured primary cells and its environmental contamination in Hawaii and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 70: 265-288.

European Chemicals Agency (n.d.). Understanding REACH. Retrieved from https://echa.europa.eu/regulations/reach/understanding-reach on 30 March 2022.

He, T., Tsui, M.M.P., Tan, C.J., Ma, C.Y., Yiu, S.K.F., Wang, L.H., Chen, T.H., Fan, T.Y., Lam, P.K.S. & Murphy, M.B. (2019). Toxicological effects of two organic ultraviolet filters and a related commercial sunscreen product in adult corals. Environmental Pollution, 245: 462-471.

Lab Muffin Beauty Science (n.d.). About Michelle. Retrieved from https://labmuffin.com/about-michelle/ on 30 March 2022.

Lab Muffin Beauty Science (2018). Is your sunscreen killing coral reefs? The science (with video). Retrieved from https://labmuffin.com/is-your-sunscreen-killing-coral-the-science-with-video/ on 30 March 2022.

Luckenbach, T., Corsi, I. & Epel, D. (2004). Fatal attraction: Synthetic musk fragrances compromise multixenobiotic defense systems in mussels. Marine Environmental Research, 58: 215-219.

MarineSafe (n.d.). Marine pollutants. Retrieved from http://www.marinesafe.org/science-and-data/marine-pollutants-identified-by-science/ on 30 March 2022.

NOAA (2021). Skincare chemicals and coral reefs. Retrieved from https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/news/sunscreen-corals.html on 30 March 2022.

Skin Cancer Foundation (2019). Sun-protective clothing. Retrieved from https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-prevention/sun-protection/sun-protective-clothing/#:~:text=Ultraviolet%20Protection%20Factor%20(UPF)%20indicates,reducing%20your%20exposure%20risk%20significantly on 30 March 2022.

Think Dirty (n.d.). Think Dirty® methodology. Retrieved from https://thinkdirtyapp.com/methodology/ on 30 March 2022.

Wollenberger, L., Breitholtz, M., Kusk, K.O. & Bengtsson, B. (2003). Inhibition of larval development of the marine copepod Acartia tonsa by four synthetic musk substances. Science of The Total Environment, 305: 53-64.

Xue, J., Sasaki, N., Elangovan, M., Diamond, G. & Kannan, K. (2015). Elevated accumulation of parabens and their metabolites in marine mammals from the United States coastal waters. Environmental Science & Technology, 49: 12071-12079.