Leopard cats appeared on my news radar twice during the last fortnight and both for rather unfortunate reasons. While the leopard cat is considered by the IUCN as a species of least concern with regards to the risk of extinction, their apparent preference for open forest and human-modified habitats often puts them in the harms way of people. Both reports are fairly common examples of what I have read about, heard or seen in the Southeast Asian region:

Human-wildlife conflict

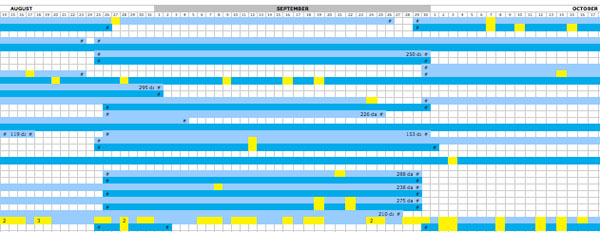

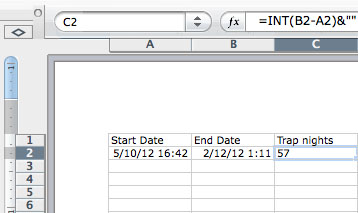

The first, Cat-ching farmer by surprise, reported by The Star on 31 Dec 2013, was a human-wildlife conflict issue where, Malaysian poultry farmer, Mohd Izham Hussin, found many of his chickens going missing until he set a trap and caught a leopard cat in it. The farmer was said to have lost about 70 chickens over a period of two months before the leopard cat was caught. He eventually handed the animal over to the Wildlife Department, saying that it “would have been cruel to kill the cat just for eating about 70 of his chickens”.

Leopard cat caught by Mohd Izham Hussin in Peninsular Malaysia. Photo: The Star.

As leopard cats are able to live in some types of human-modified habitat with vegetation cover, their proximity to humans can often lead to conflict if poultry or small livestock and pets become part of the leopard cat’s diet. Personally, I have been told of how a villager’s chickens and rabbits were killed and eaten by a leopard cat in Singapore in the old days. Indeed, Harrison in his book An Introduction to Mammals of Singapore and Malaya (1966) noted that the species can be a “notorious chicken-thief”.

Most people’s perception of human-wildlife conflicts often involve big animals like elephants or tigers, but small carnivores such as small wild cats, civets and otters have their share as well. In many cases, these animals end up being persecuted by people.

Even though leopard cats in Singapore may not get into similar conflicts these days with people, I think this incident is a lesson worth learning from – that Mohd Izham Hussin spared the animal despite the threat it had on his livelihood. I am trying to contact Mr Mohd Izham Hussin through the journalist so see if there is a way to help.

Poaching and leopard cats in the pet trade

The second report on Rare leopard cats sold for $2,000 on social media appeared on the Borneo Bulletin, 14 Jan 2014. It was stated that leopard cats have been sold as pets online in Brunei, and are a target for poachers for their pelt.

Quite similar to the songbird’s curse of its beautiful song, leopard cats, owing to their attractive appearance, are prized as exotic pets and for the fur industry. They are also used to breed a domestic cat hybrid called the Bengal. For these reasons, some pet stores and markets in the region, such as Indonesia and Myanmar, stock them rather openly. As most of these animals are likely to be sourced from the wild, hunting could eventually be an issue for the species in some areas.

It is important to note that the leopard cat is listed as a CITES Appendix II species in most countries, meaning that international trade in leopard cats is illegal. Also, most wild animals do not make good pets as they may be untameable and have strict diets that cannot be fulfilled in captive conditions, i.e., they belong to the wild.

Although it is not clear if the leopard cat that was reportedly put on sale for $2,000 was rescued, it appears that the Universiti Brunei Darussalam wildlife club, 1stopbrunei Wildlife, has rescued and returned leopard cats and other wild animal back to wild. In addition, the club also conducts talks and field trips for school to spread awareness for wildlife protection.

A leopard cat rescued by Universiti Brunei Darussalam wildlife club, 1stopbrunei Wildlife. Photo: M Shavez Cheema.

In the end, although both news articles have rather unfortunate beginnings, both also have silver linings: one with a poultry farmer who decided not to kill the trapped leopard cat, and the other, a wildlife club doing good work to rescue wild animals and spread awareness for wildlife protection. I think we can certainly be heartened that there are many in the wildlife conservation movement out there.