Yellow fish hiding in discarded pipe (Image by Jenny Huang under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license.), Edited by me

It’s been 7 weeks in real time and we’re still on the surface. That won’t do, so take a deep breath, and let’s go for our first dive!

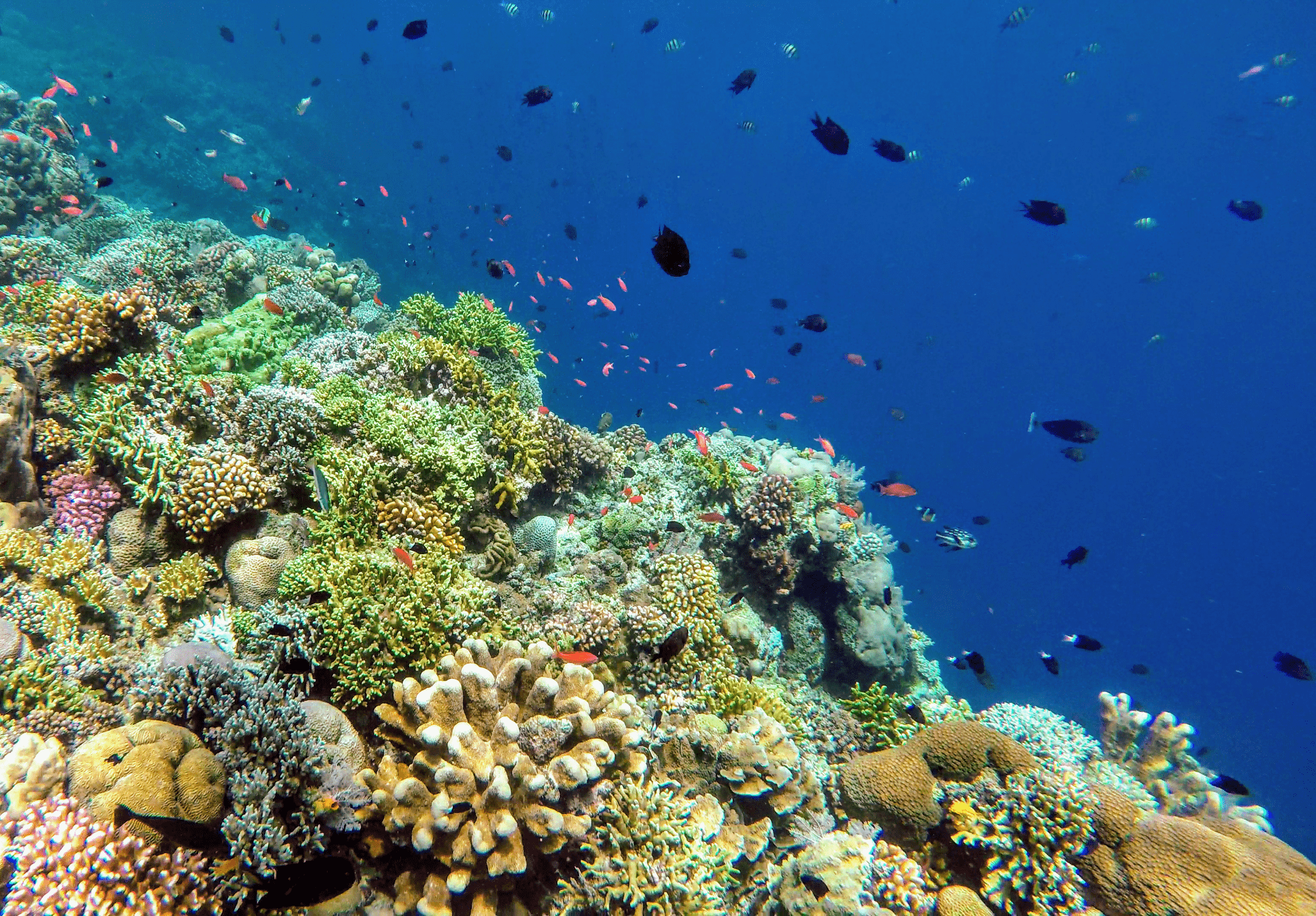

Diving in Bunaken (Image by Victor under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) license.)

I know I’ve been speaking lots about colourful reefs in Manado – it’s the reason why I learnt scuba diving. However, as soon as you submerge, you realise your surroundings aren’t what I promised.

At first glance, the ocean floor looks barren and dirty, and you’re probably wondering what you signed up for. There are so many different dives to choose from – wall dives, reef dives, night dives… Couldn’t I have picked a better one?

Today, let’s go “Muck Diving”.

It doesn’t sound too pleasant, and for most on their first dive, it’s even less appealing on sight. Not only is the sand coloured black, all thanks to North Sulawesi being bounded by many active volcanoes, it’s also littered with manmade debris like glass bottles, metal cans, shoes and even bicycle frames.

Motorcycle Wreck (Photo by tomfreakz under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) license.)

As a 13-year-old who didn’t know much about marine pollution, I thought it was hilarious. However, after learning so much about how our oceans are in jeopardy from almost everything we dump in it, it got me thinking about what I’d do as a more informed individual.

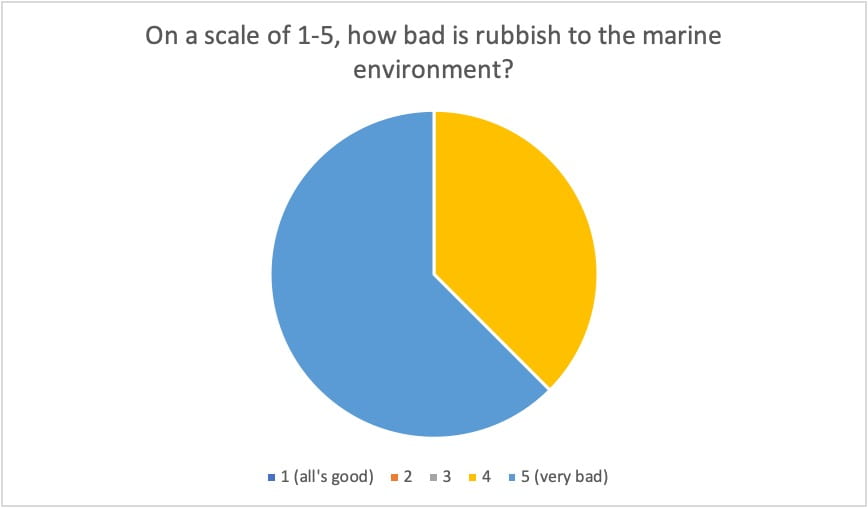

If I saw any form of trash that I could throw or recycle, I’d do it without hesitation, and I’m not the only one. Out of the 16 responses I got from 47 BES students, more than 50% said the same.

Now, I’d like to focus on those who’d ignore it and the ones who’d survey the situation before taking action. It’s tempting to find out who they are and wonder why they do as such, but… they’re not actually wrong.

For starters, many creatures found in muck dives are either small (they’re known as critter hotspots for a reason), masters of camouflage (you need time and patience here) or lack predators (i.e. nudibranchs).

Can you spot the Pygmy Seahorse? (Photo by Steve Child under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license.)

However, as with all things, there are exceptions, just like this Golden Goby, who has now used the drink can to seek refuge from the dangers out there (i.e. frogfishes, you find many of them quietly waiting to ambush their prey here).

Golden Goby in a drink can (Photo by Christian Gloor under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license.)

With this, doesn’t it become a dilemma, because by simply clearing the ocean, you might end up being the one bringing about unintended and adverse consequences for doing something “good”.

In fact, it’s almost as if you’re taking away parts of a reef, albeit small and artificial. How does that sound?

On larger terms, let’s look at shipwrecks. Some call them harmful, but they are one of the most common sources of artificial reefs. If done right (i.e. placed on empty seabeds), they can harbour a wide variety of species, from corals to predatory fish, and become a whole ecosystem, as well as a whole type of dive on its own.

Wreck Diving (Photo by Marcel Ekkel under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) license.)

From this, perhaps trash isn’t as terrible as we think they are.

However, this doesn’t mean the oceans become even more of a dumping ground. We know all too well on the effects of plastics to marine life and the fact it has become the reason why some are threatened by extinction, but I’d like you to take a step back with what’s already in there. Perhaps we could start practicing discretion and consider what could possibly arise from our “good” actions.

It’s a point of view we don’t see often, but like they always say, isn’t too much of a good thing a bad thing eventually?

Hi Nat!

Thanks for bringing me through this virtual diving excursion. It is really informative as to how seemingly inconspicuous rubbish on the seabed can become artificial habitats for marine species. I never knew ‘muck’ could provide such an advantage. Honestly, when I saw the photo of the motorcycle covered in rust and all, I was quite taken aback how these metallic, bulky things even end up on the seabed, as a whole. Normally, I associated marine trash with just floating plastic and industrial wastes, but this actually allowed me to gain more insights into the things that humans would discard into oceans without a second hesitation.

That aside, in the opinion piece, you mentioned that these sunken trashes can ultimately become part of the synthetic makeup of ecosystems and habitats, including reefs. Hence I was wondering (might be a little bizarre) whether countries are able to stockpile all these heavy objects and discard them systematically in designated locations that lack coral reefs or face degradation of natural habitats? Will this eventually lead to increased deposition of heavy metals (cars or bicycles) into seas and oceans? Hope to hear from you!

Hi Wenhan, thanks for stopping by! However, before we get into anything, I’d like to apologise for the late reply as I didn’t receive the email notification for this comment and only realised that you sent in something when I opened NUS Blogs. With that being said, I hope I’m able to provide a reply that will make up for this lateness.

First thing’s first, you’re very welcome for this virtual diving excursion, and I’m actually really happy you seem to have enjoyed reading this blog entry. If I were to be very frank, I didn’t understand what was so great about muck diving because all I could remember seeing was empty black sand, and rubbish of course, that stretched as far as the eye could see, though I have to admit that it was probably a good choice as an amateur diver (I did some of my mandatory dive exercises in these spots) – there’s a lesser chance of me accidentally destroying something or disturbing one of these critters’ habitats. However, what I do remember was finding a whole family of clownfish in the middle of nowhere (it was really cute, though I’d suggest not getting too close to their homes as they can be quite aggressive), and being fascinated by the variety of trash, especially shoes because it was fun guessing their sizes. Sometimes, we’d even play a game as a group to see if we could find the other shoe sometime later during our dive. In fact, it’s all these memories that make it a fun type of dive, but personally, I like seeing bigger creatures. Nevertheless, this was quite fun to share and research on as well, and while it shouldn’t change your opinion per se on marine pollution due to trash (because of all the harm it brings), I hope that it does get people to start thinking about being selective with what we clean up because as established, we might end up destroying a creature’s home altogether. If I understood your comment correctly, it seems like you gained that insight, and from that, I’m happy you did!

Moving on to your question, I’d like to say that it’s actually possible! In fact, as I was researching, I came across this case study in Delaware, a US state, where artificial reefs were built out of train carriages that were no longer in use, and based on what I’ve read, it’s been doing extremely well, harbouring about 30 to 40 species that could serve as food for the fish in the area. In short, it almost seems as if it’s become an entire ecosystem of its own. Furthermore, they were also placed in strategic locations (i.e. a bare sand bed), which definitely contributed to its success (i.e. if it were to be thrown into a place that already had coral reefs of its own, it is likely that these structures will end up destroying whatever’s already there) and ensured that the chances of potential devastating consequences, as seen in the link previously, are low (i.e. if something were to go wrong, it would not affect as much as compared to if it added on to an actual natural reef). Based on this and what I’ve seen personally, it is probably possible to stockpile these objects, and it’s not bizarre at all! However, it is worth noting that not everything can be simply dumped into the ocean. In this blog entry, I replied to Rachel Ong’s comment about the prospect of artificial reefs and included some case studies that did not turn out successful, but of course, you could find some information here too! In a nutshell, if one were to stockpile such objects, they must fulfil a set of criteria and that includes the fact that they should definitely be sturdy and easily secured, and should not be made of materials that have the potential to leak toxic chemicals into the ocean, as we’ve seen with Osborn’s case of the artificial reef made of tyres, where none of the aforementioned criteria was met.

To end on a more personal note though, based on my own dive experiences, I would very much prefer seeing more natural reefs as compared to manmade ones, which is why I believe more in us making changes to our daily life (they could be small, like using less plastic bags, but like Mother Teresa implied, small things can go a long way), for example, that would benefit the environment rather than finding band-aid solutions to combat the problem. However, I too acknowledge that if we leave everything up to nature to fix itself and continue with our lives, we’d probably be worse off, so at the end of the day, it comes down to the fact that we need multi-faceted solutions, both short term (i.e. artificial reefs) and long term (i.e. awareness and education) to ensure that we preserve as much of the natural habitat as possible. I mean, won’t it be a little sad if reefs ended up being made completely out of the things we throw away? If that were the case, I think it really sets things into perspective on the point that we end up throwing away so much that we had to turn to the oceans to contain them (as if it’s not bad enough) and tell ourselves that it would prove to be something good at the end of the day. It just doesn’t sit right with me hahaha.

Anyhow, I hope I provided you with the answer you were looking for, as well as my personal thoughts! Have a great one ahead!

Hi Nat

No worries at all! Loving your reply too:) I am looking forward to your future posts.

Hey Natasha!

I never knew a soda can could actually be a refuge for fish instead of just refuse! Do you think that this could be a feasible way to not only utilise certain types of discarded materials, but also promote the survivability of certain species of fish? If done in a conscientious manner, it could be a viable way to reduce the amount of waste incinerated or sent to landfills.

Cheers!

Joseph.

Hi Joseph, thank you for your comment and I’m glad to know that I was able to share some new information with you! To be completely honest, I wasn’t surprised with the survey results because as we’ve all learnt at some point in our lives, when we see something, we should take the initiative to throw it away, and as BES students, it seems like the feeling to do so is even stronger. However, with this blog entry, I hope that I was able to shed some new light on how trash could possibly be perceived (i.e. as much as we associate them with death, they could also be seen as a new chance at life). However, as I’ve also mentioned in this entry, it’s more of practicing discernment towards actions that could be deemed as good rather than simply following what others deem as the right thing to do. It’s almost as if we need to stand our own two feet with regards to this matter and decide for ourselves what is right. Personally, throwing trash away might help to make an area more appealing, but if we’re taking away a home for a creature that has managed to make use of it, doesn’t that sound worse? As established in Dr Coleman’s recent class, even the creatures in question are considered as stakeholders, which means that they do have a “say” in this, so with that, what we think is good might not translate to the creatures in question (and it doesn’t help they don’t have a voice either, because if they did, I’m pretty sure they’d say something if one were to be taking away their home). That lesson really set things into perspective when thinking about this blog entry hahaha.

However, it seems like the content you’d like me to cover is quite similar as to the content I provided to Wenhan’s comment, where I discussed about using discarded materials such as automobiles to contribute to the making of an artificial reef. In a nutshell, it’s possible, but there are definitely factors to be taken into consideration when making an artificial reef, which then affects the types of trash that could contribute to this whole idea (i.e. bigger and heavier material tend to do better as foundations for artificial reefs). Therefore, with this in mind, I wouldn’t say I’m completely certain whether it could reduce the amount of waste incinerated or sent to landfills. For instance, the trash that I saw during my muck dives weren’t deliberately placed, and according to my dive master, they come from the villages nearby who discarded them into the ocean. However, I personally feel that the trash I found such as glass bottles and paint cans wouldn’t be viewed as a good thing by the general public to be introduced into the ocean, so it is likely that they’ll still be considered as general waste, not as something that will be considered as foundations for artificial reefs. However, as for the bigger materials, as discussed with Wenhan, they’ll definitely contribute to the reduction of what’s in the general waste stream, given their size and the materials used to make it in the first place, and the best part? They actually work, as we’ve seen in the case of Delaware and shipwrecks! In short, while the smaller items might not prove too big of an impact, given that they aren’t exactly the best foundation, it’s a comforting thought to think that there’s still hope with the bigger items that are no longer in use!

I’ve provided some case studies in my response to Wenhan, as well as Rachel Ong who commented on my blog post about 4-5 posts back, so feel free to check those out! If there’s anything at all that you’d like me to discuss further, feel free to leave a comment again! For now, have a great one ahead!

Hi Nat! Such a punny and interesting read! I never knew that nature is able to transform the garbage we discarded to the sea into a refuge for certain species. Adding on to Wenhan’s opinion, could I ask if creating an artificial reef using these selected garbage pieces could be classified as reusing and recycling, causing it to be sustainable? What are the costs and benefits of creating such artificial reefs?

Hi Sherry, thank you for your comment and I’m glad you enjoyed the read! First thing’s first, I apologise once again for the late reply as this comment did not come in through my Outlook either and it was only when I scrolled through Blog.nus did I realise that you actually sent in something. With that being said, I hope this response to your question was worth the wait!

As I read through your comment, the first thing I noticed was the usage of the words “reusing” and “recycling”, and it brought me back to my younger days, especially when I was in Polytechnic, simply because I thought they were the same thing. Fret not though, you’re not alone, and despite being environmental science students, my lecturer was shocked when she found out that most of us thought they were the same. In short, reusing refers to the extension of a product’s lifespan (i.e. you’re using the same product for something else) but recycling refers to using the materials to make another product altogether (i.e. how plastic bottles can be turned into shoes), and with that being said, I’d tend towards “reuse” in this particular case. However, I wouldn’t say that this automatically leads to sustainability, especially when the wrong materials are used (as seen in the Osborn case), and I’m pretty sure that we ourselves wouldn’t want to be the ones responsible for contributing to the already large amounts of trash in the ocean. Nevertheless, it would be worth noting that in the case of Singapore’s artificial reef, which I featured here, this could be considered as “recycling”, given that it required a variation of materials (which were also well studied to ensure that they don’t end up polluting the environment) to make another product altogether, and this would definitely be the more sustainable one of the two options (i.e. building an artificial reef structure VS using trash). Not only is it sustainable in terms of the fact that it uses leftover construction material, it is also said to last longer (given that its made of concrete, and it’s also easy to repair) and a lot safer too (i.e. no leakage of any harmful chemicals into the ocean).

Onto the next part of your question about the costs and benefits of artificial reefs, it’s safe to say that nothing goes without costs, despite it being so pretty and an alternative for us to repurpose our waste into something meaningful. However, let’s start positive, and I believe the benefits would be in terms of the fact that artificial reefs are able to provide a home for species to colonise in places that’s not for everybody (i.e. a barren sand bed) and it also helps to contribute some complexity into the system, which thus enhances biodiversity. Furthermore, it could also serve as another potential dive site and perhaps provide another type of dive for both tourists and the locals. In terms of the costs, one of the things I can think of is that it might attract too many people (i.e. it might unintentionally attract too many tourists which is more than the dive site can handle at any one time) or another is that it could potentially damage the surrounding areas. However, I’d say that these can be easily solved with strict measures and thorough studies to ensure that the reef is able to thrive without too much disturbance and to also make sure that it does not get introduced to a place that already has health coral reefs for example. Even when one of the concerns of artificial reefs are the fact that they’re not on a map, I’d say this would be relatively easy to solve if it were actually promoted either as a place to be or a sanctuary. With more people talking about it in general, it is likely that it’ll make a name for itself, with or without a map, and with all that being said, I believe that the benefits would outweigh the costs as long as proper measures are implemented to ensure that’s the case.

I hope this was a response that you’d deem good enough and once again, apologies for making you wait so long for this response! Also, thanks for getting me to think about how I personally felt about such artificial reefs too! ^_^ Have a great day ahead!