Finally, after 4 long weeks of planning and mental preparation (I didn’t get this luxury), we’re finally in Manado – the capital of North Sulawesi, Indonesia!

And this time, welcome to the place where my diving journey began.

I don’t exactly know why my dad chose Manado (he thought it wasn’t exciting), but I’m convinced he finally saw the opportunity to get me to dive by enticing me with the most colourful and attractive reefs I had ever seen at that age.

He succeeded with snorkelling, and with how adamant he was to get me to dive, it came as no surprise he did it again.

And if he didn’t succeed, this blog wouldn’t have existed.

To most, diving seems simple – all you need is the equipment, basic swimming skills and sheer water confidence, and you’ll be good to go. However, quite a fair bit of time is actually spent on textbook theory and practice before you head out to where the wild (and beautiful) things are.

It isn’t just because your life’s potentially on the line, but if you’re not careful, you might end up leaving a trail of destruction behind.

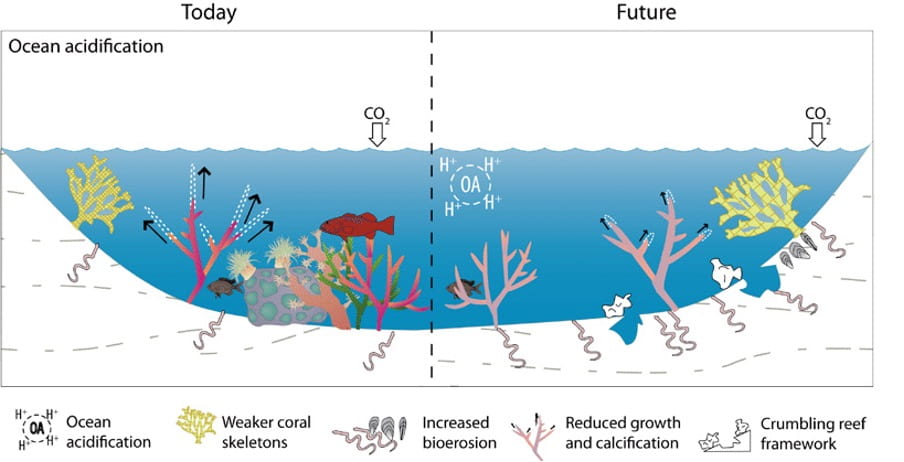

Two weeks ago, I featured this infographic, and today, I’m bringing it back.

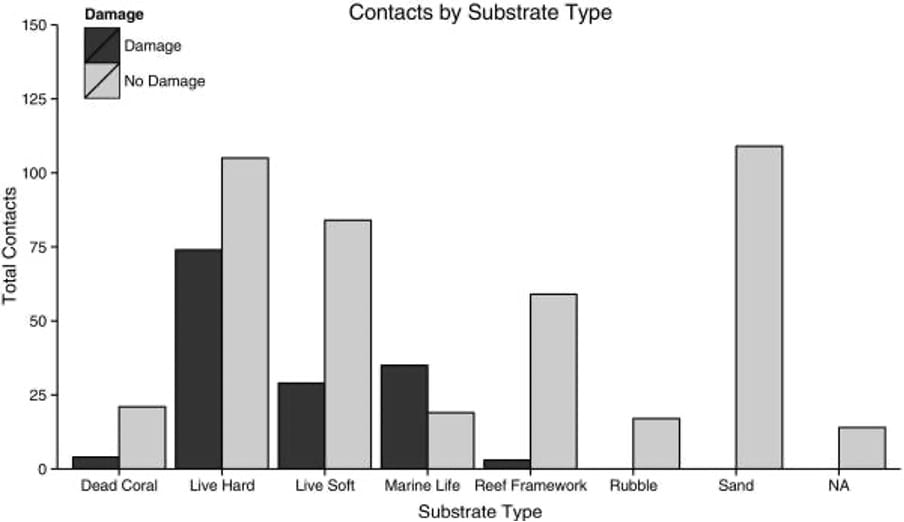

According to a study assessing the correlation between diving practices and their subsequent impacts, it was observed that live hard corals and marine life experienced the most damage, relative to how many of them managed to escape that fate.

Graph from Recreational Diving Impacts on Coral Reefs and the Adoption of Environmentally Responsible Practices within the SCUBA Diving Industry under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

Interestingly, hard corals aren’t actually resistant to damage. In fact, because they produce more calcium carbonate, combined with the problem of ocean acidification, they’re more susceptible to damage than we think.

Thinking back, it all makes sense now as to why finning techniques and buoyancy controls are important (especially when hard corals are the ones constructing the reef), because you do not want to disrupt an already fragile environment. Furthermore, it’s also for safety, because the last thing you’d want to crash into is a blue-ringed octopus.

While diving gloves are discouraged, I personally needed it after getting stung by a soft coral, and that’s where you need to listen to your dive masters and be conscious of your actions. When you’re diving in Manado, Bunaken National Marine Park’s probably on the agenda, which is home to 20 times more reef fish species than Singapore.

Bunaken National Marine Park (Image by Matt Kieffer under Creative Commons Attribution – -ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) license.)

The rules are strict, and if you do breach them, it’ll be a heavy sentence. The briefing and entry form might be long, but it cannot be longer than the time it takes for a coral to regenerate (and you can imagine how increasingly difficult this is now).

While the future seems bleak, it doesn’t hurt to hold onto a glimmer of hope. When I was there, it’s clear how much the dive masters cared for the marine environment, especially with how serious they were when it came to ensuring the number of divers at any dive site remained within the quota, and emphasising time and time again not to touch anything underwater. On this note, shouldn’t we at least respect what many call home?

After all, if you think about it, everything begins with the protection of the reef, all the way to the depths of “Atlantis”.

Hey Natasha!

I didn’t realise how much theory goes into it! What kind of content do you need to learn? Is it about the marine life, or actions the divers take? I bet diving has so much potential to instill the passion for conservation in people, because they get to be within the ecosystem to see for themselves why it is so worth protecting 🙂

– Anna

Hi Anna! Thanks for stopping by and truth be told, even I didn’t know that there was a bigger purpose to being so technical with diving! I always thought that it was only for the sake of efficiency (especially in times when there’s currents) or safety (because that’s one of the things that’s extremely important when one learns how to dive), but who knew it was also a way of protecting the beautiful creatures below the surface? As I mentioned in my second blog post, there are times when we just can’t help it (i.e. it’s either we hold on or get swept away into the deep blue, which happens sometimes with wall diving where the corals are growing on the side of an underwater cliff), but if given the opportunity to do whatever we can for the environment to the best of our ability (and it’s really not difficult too), why not just do it anyway? We could kill two birds with one stone by taking care of ourselves and the environment too, and at the end of the day, none of us have anything to lose.

As with typical diving lessons, it is no surprise that the content’s heavily based on ensuring that we dive safely, and this comes in the form of dive techniques (especially in times of emergency, or even when you’re surfacing, those lessons are extremely important because it could make the difference on whether you end up in a hospital or not) and being familiar with the many equipment that we have. However, there’s always time to spare to learn a little bit about marine life, and that’s in the form of various hand signals we can use to show other divers what we have seen! And besides, when you do go for an actual dive, you’ll realise that most of the dive’s simply appreciating the surroundings around you and as long as you get through your exercises calmly and safely, I believe that you’ll have no issues getting the dive certification at the end of the day. In a nutshell, let’s just say that you get quite the holistic learning experience because you not only learn the theory (and sit for a test), but you’re also given the opportunity to be on your own to a certain extent and put all these skills to the good use. And of course, you’ll also learn about all the cool marine life as you go, and one of my personal favourites is the electric clam!

Finally, with regards to the last bit of your comment, I definitely agree with that statement (i.e. that diving sparks the desire to conserve). In retrospect, if I didn’t dive, I don’t think I would’ve fully understood as to why there’s a need for protection. Back then, my rationale was extremely superficial, and it was only based on the fact that the coral reefs were pretty. Now, I’ve come to understand and appreciate the good that it brings, and I would very much love to be a part of this ongoing conversation, which simply brings me back to why I started this blog in the first place – to shed some light on the world we know so little about, and hopefully, spark something in somebody to encourage them to see all these things for themselves one day.

K, that disco clam is totally crazy. Also, I love that we (assuming the video is accurate) don’t know why it has this adaptation.

Another great post, Natasha !

jc

Hi Dr Coleman! Once again, thank you for the comment and I’m glad you enjoyed the content as much as I loved writing it and coming up with the whole idea for this post! I have to admit that while I was in the process of writing, I got distracted for a bit as I ended up flipping through my textbooks and my log book, especially, but it sure was a good trip down memory lane! In fact, as the week went by, I even went to check out NUS’ Dive club’s Instagram page and who knows, I might just invite my BES batchmates along for a course or even a trip together! I think it’ll be pretty fun, though I’d probably need the refresher course before I do that (and turns out that I missed the one that took place last week, but I’ll try my best to keep up with their activities now) hahaha!

I did some research on the electric disco clam, and while the reason for the adaptation is still being studied (it’s truly interesting how the discoverer of the clam took up a whole PhD just to study it), it seems to be the result of bioluminescence, because the clams contain silica, which acts as a light reflector, and the other side of its opening’s good at absorbing light. Hence, whenever this opening in order to breathe, what you get at the end of the day is a beautiful display of what looks like electrical sparks. As much as I had hoped that it actually does generate electricity (we made a running joke that it might just be able to charge our cameras haha), it’s still pretty cool anyway. However, what I did manage to find was that typical clams could actually be used as a source of renewable electricity (source)! While it might not sit well with some (i.e. is it actually right to “exploit” living organisms for our own sake?), I thought that it was pretty interesting regardless, and personally, if it was done right (i.e. the clams are of a breed that aren’t considered threatened or they do not contribute to food security issues, like what we’ve seen with biofuels), I think it could actually prove to be quite a step in the right direction where sustainability is concerned!

Once again, thank you for stopping by, and I hope to see you in the upcoming posts, especially when it comes to the blog posts about actual diving! I’d love to hear more of your personal experiences in the deep blue!

So the clams could be like the human population in the Matrix. Interesting.