Plastic in our Oceans

Since the mass production of plastics began in the 1950s, global plastic production has increased rapidly. In 2015, global plastic production amounted to 381 million metric tons, around 200 times that of plastic production in 1950 (Ritchie & Roser, 2018). Just look around you’ll find that plastics are everywhere. It is undeniable that plastics have since become a staple in our lives, offering various benefits, including increased hygiene standards for food packaging.

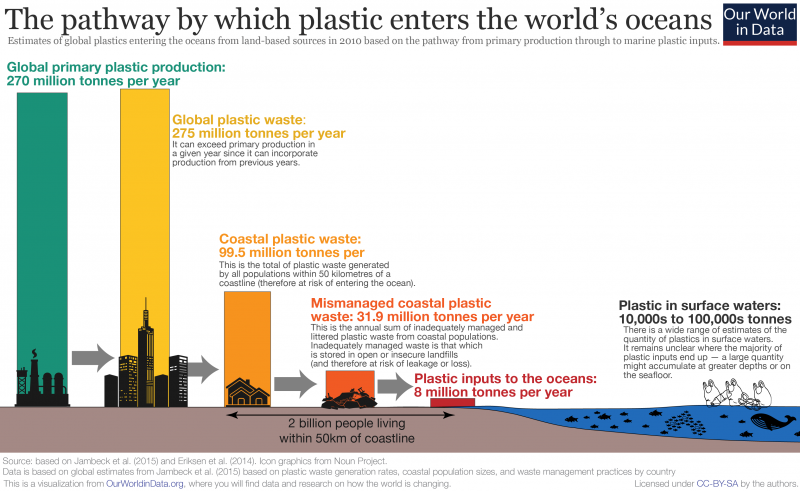

Yet, the mismanagement of plastic waste resulted in the input of 8 million metric tons of plastic into the ocean in 2010 (Jambeck et al., 2015). Plastic waste is deposited into the oceans through rivers, sewage outfall, or even transported by ocean currents and the wind. High levels of plastic waste were found “on a remote Arctic island over 1000km from the nearest town or village, taken there from all countries bordering the Atlantic by the ocean currents” (Royal Geographical Society, 2015, p. 17), denoting the severity of marine plastic pollution. According to Jambeck et al. (2015), the annual input of plastic waste into the ocean is set to double by 2025 to 16 million metric tons, with cumulative inputs estimated at around 155 million tons.

Figure 1: How mismanaged plastic waste can enter our oceans (Ritchie & Roser, 2018)

If having an obscene amount of plastics in our oceans wasn’t enough to convince you of the gravity of marine plastic pollution, perhaps considering the physical structure of plastics will. Plastics are polymers produced through the polymerization of monomers. For instance, ethylene (C2H4), a monomer consisting of two carbon atoms and four hydrogen atoms, has a C-C double bond. By breaking the C-C double bond to chemically combine the carbon atoms of different ethylene monomers into a long repeated chain, we can then produce polyethylene, a type of plastic used in toys (Sharpe, 2015).

While these C-C bonds holding the long-chain polymers are what makes them so durable, it unfortunately also means that most plastics are non-biodegradable. This is because breaking down the C-C bonds requires a large amount of energy, and to date, there have yet to be any organisms that have evolved to do so (How It Works Team, 2019). Some plastics may take up to hundreds of years to break down, and others may not even do so. Ergo, the excessive amount of plastic waste in our oceans is here to stay for a very long time.

References

How It Works Team. (2019, April 21). Plastic: The science behind the indestructible. How It Works. https://www.howitworksdaily.com/plastic-the-science-behind-the-indestructible/

Jambeck, J. R., Geyer, R., Wilcox, C., Siegler, T. R., Perryman, M., Andrady, A., Narayan, R., & Law, K. L. (2015). Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260352

Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2018). Plastic Pollution. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution

Royal Geographical Society. (2015, June 12). Plastic Pollution in the Ocean. 21st Century Challenges. https://21stcenturychallenges.org/plastic-pollution-in-the-ocean/

Sharpe, P. (2015, August 31). Making Plastics: From Monomer to Polymer. https://www.aiche.org/resources/publications/cep/2015/september/making-plastics-monomer-polymer