Where can you find a rainforest and a wetlands side by side? Two Saturdays ago, I experienced just that – a tour by Prof. Gretchen of the Keppel Discovery Wetlands as well as Tyersall Learning Forest, two restored ecosystems in the Singapore Botanic Gardens (SBG). They support a dizzying variety of biodiversity and provide a chance to get up close with unique species such as the world’s largest orchid, the tiger orchid, as well as towering dipterocarp trees, characteristic of tropical rainforests. (It’s a must-see for anyone who wants to learn about Singapore’s natural landscapes of the past!) On the tour, I learnt about the conservation and restoration work that SBG has been engaged in and began to understand the challenges surrounding conservation.

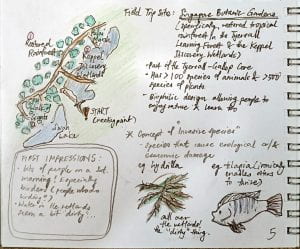

Fig. 1 A brief sketch of the area that I visited

Without a doubt, conservation can and should be a welcome activity. Take the case of the ex-situ conservation of tiger orchids – a large individual in the SBG bore fruit and was harvested in 1996! Seedlings were propagated and reintroduced in various locations such as Orchard Boulevard and Pulau Ubin, where it was once native. Thanks to conservation efforts, the tiger orchid was saved from extinction, which was the fate of a whopping 154 other orchid species that used to be found in Singapore. Today, a tiger orchid island sits at the entrance of the wetlands, free for all to appreciate and enjoy.

Fig. 2 The island of tiger orchids (Grammatophyllum speciosum Blume, native to Singapore, and presumed nationally extinct by the National Parks Board (NParks)) at the entrance to the wetlands

Nevertheless, problems abound when the public begins to encounter conserved flora, fauna, and environments without prior education. For instance, in the wetlands, we encountered birdwatchers who Prof. warned would, through innocent photo-taking, spread the news of rare bird sightings and inadvertently attract poachers that might harm these birds. Further on in the rainforest, we had a stand-off with a juvenile long-tailed macaque who came too close. A jogger brushed it off as “harmless” – she was unaware that abetting such close contact with humans could be extremely dangerous. It is such human-nature interactions that reveal the challenges in conservation: we can restore nature, but that cannot be all – what of conservation when it comes up against such ignorance?

Fig. 3 An unidentified bird through the lens of a birdwatcher (“birder”)

Fig. 4 An encounter with common long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis), native to Singapore, and vulnerable under IUCN)

I believe the answer to this conundrum lies in SBG’s educational power– something it has already embarked upon. Signages on how to deal with animal encounters as well as warnings on the potential effects of trending hobbies (e.g. birding, an emerging phenomenon), could be better designed and installed more visibly at sites of frequent encounter; tours that emphasise the restorative efforts and their threats (updating accordingly depending on trends) could be conducted; and lastly, in the online sphere, creative content about conservation work can be disseminated through platforms such as Instagram (and its Reels function), where the National Parks Board boasts nearly 60, 000 followers. Ultimately, in a world with changing trends and, in a (to-be) City in Nature, it is imperative that outreach efforts are dynamic and creative in order stay relevant and reach as many as possible. This way, conservation efforts will be truly sustainable as everyone respects nature.

Written by: Tan Wei Hui, Joanna

Leave a Reply