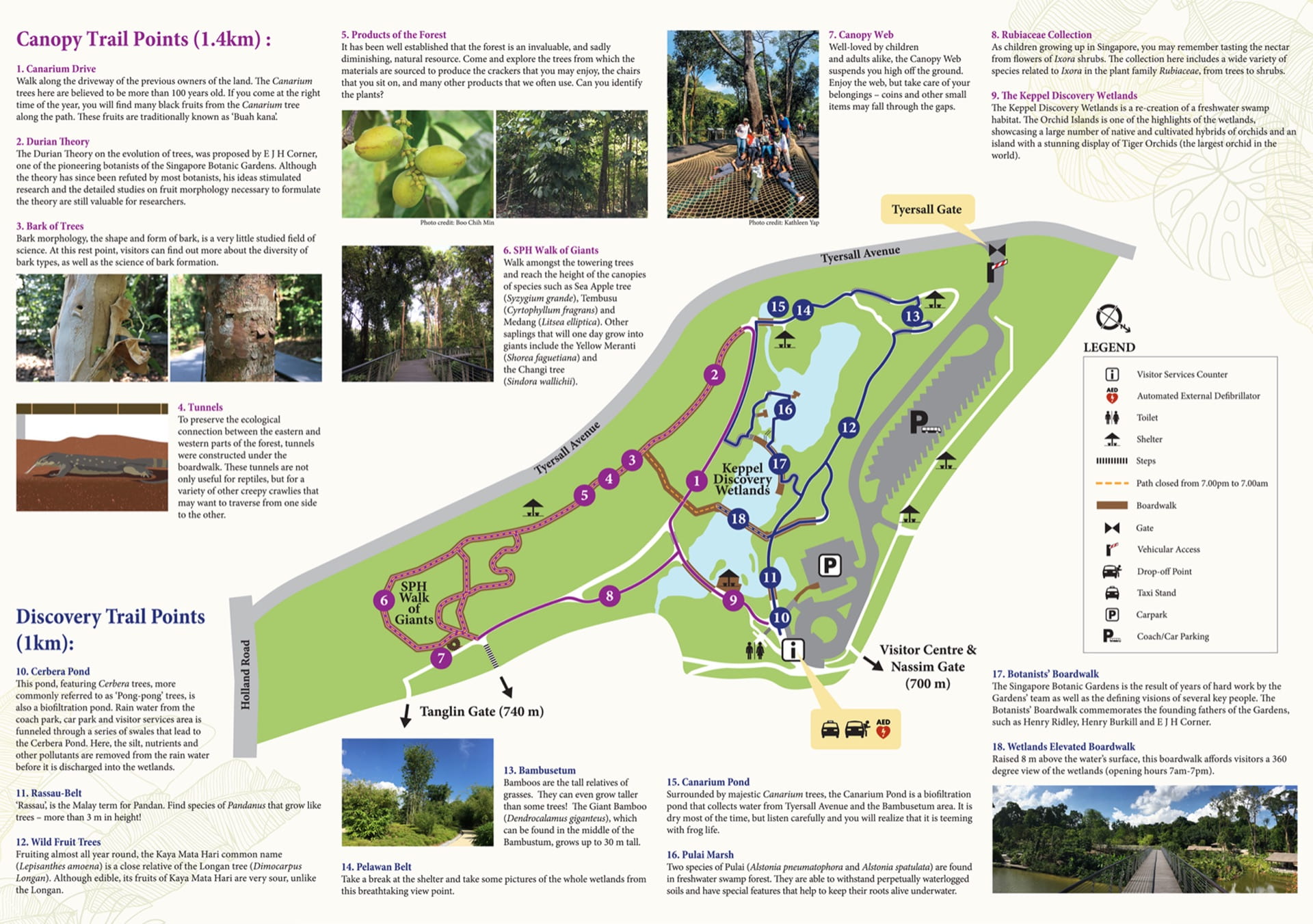

Here’s an experiment: ask your Singaporean friends to name you a few flowers that come to mind immediately, and I bet the most common responses are probably roses, sunflowers, tulips, chrysanthemums, or cherry blossoms. After all, these flowers have been so heavily embedded in popular culture that they can be recognised by even the most nature-adverse person on the street. But here’s the issue – why only roses? Why not some flowers native to Southeast Asia? As a flower enthusiast, I feel bad for all these gorgeous native flowering plants which are often overlooked by the public. Fortunately, the Singapore Botanic Gardens (SBG) recognises the value of these plants, which are now tucked away safely in the Learning Forest, comprising a tropical lowland forest ecosystem, and a restored wetland ecosystem (Figure 1). These ecosystems house a wide diversity of native flora in their optimal growing conditions, which exemplifies SBG’s key objective of conserving plants of horticultural and botanical interest. I managed to identify several different flowering plants with iNaturalist during my visit to the Learning Forest with my NUS GE4224 class.

Figure 1. Map of SBG Learning Forest, which comprises a tropical lowland forest ecosystem (SPH Walk of Giants) and restored wetland ecosystem (Photo credit: SBG).

The ecosystem services of tropical forests include climate regulation, and cultural services such as education, recreation, and tourism. In addition to the construction of a boardwalk, rare and emergent trees have also been planted as part of the Learning Forest’s restoration efforts. The multi-strata tropical rainforest ecosystem features terrestrial flowering plants such as the large-flowered uvaria (Uvaria grandiflora), which I found growing beneath its leaves (Figure 2). This was especially fascinating, and I think this adaptation helps the flower avoid direct sunlight and the consequently high temperatures in its surroundings.

Figure 2. Large-flowered uvaria (Uvaria grandiflora) (Photo credit: Zhong Jialing).

Meanwhile, the key floral highlight of the Keppel Discovery Wetlands perched itself on artificial rock islands in the eco-lake. This intriguing plant is the native tiger orchid (Grammatophyllum speciosum), which only blooms once in several years. As a lithophyte, it grows on rocks and feeds on nutrients from rainwater and nearby decaying organic matter. This characteristic allows it to be displayed in a restored wetland ecosystem and in close proximity of visitors, despite being a terrestrial plant. The artificial rock islands also prevented the native orchids from being affected by the deteriorating water quality in the eco-lake, caused by a hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) infestation. The herbs formed a layer of greenish-yellow organic matter on the water’s surface (Figure 3), and perhaps it was fortunate that there were hardly any aquatic flowering plants in the vicinity of this invasive species.

Figure 3. Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata)-infested eco-lake (Photo credit: Zhong Jialing).

Despite being in awe of these native flowering plants, the trouble concerning hydrilla extermination in Keppel Wetlands makes me doubt if aquatic flowering plants may be introduced into the ecosystem anytime soon. I suppose it would be more viable if SBG puts more effort into ensuring the longevity of ecosystem restoration, before increasing the number of species in the Learning Forest. It is only when conservation efforts remain sustainable in the long term that visitors will have the opportunity to appreciate these rare blooms in their natural habitats.

Written by Zhong Jialing

Leave a Reply