Hello everyone!

Previously, I wrote about the extent of overfishing in our seas. This led me to think: How are all these fishes being caught? Let’s look at some commercial fishing methods!

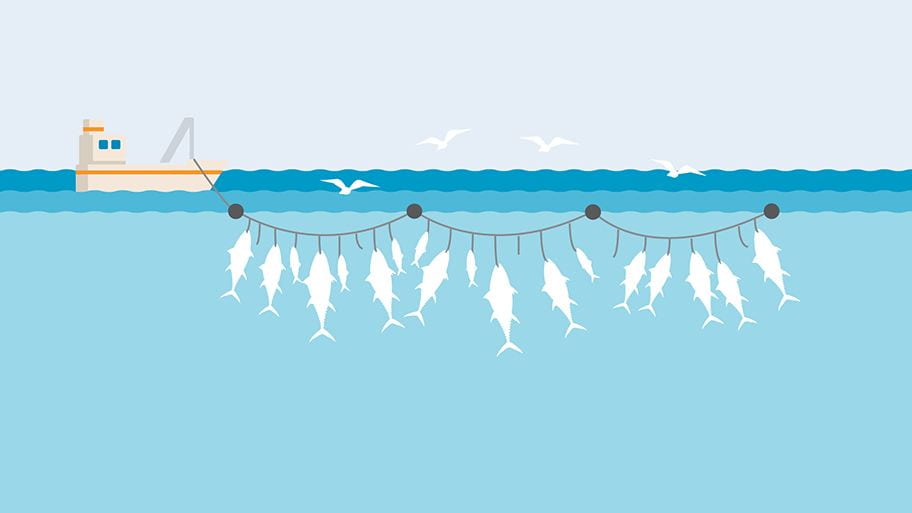

You probably know how the recreational angler fishes – with a fishing line and hook. It’s sort of like that in longline fishing too.

As the name implies, a long fishing line with baited hooks attached at regular intervals is left in the water, and fishing vessels wait till fishes are caught – hook, line and sinker! – before reeling it in. Unfortunately, non-targeted species can get hooked by accident, also termed as bycatch – creatures unintentionally caught by fishing gear in use. Longline fishing in pelagic waters (midwater section of the sea) are especially prone to high turtle bycatch, thus posing a threat to sea turtle populations, such as leatherbacks (Swimmer et al., 2017).

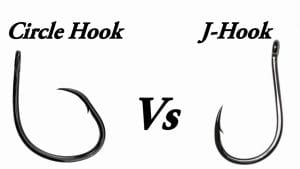

Fortunately, efforts have been taken to address this issue, such as replacing J hooks with circle hooks, which is effective in reducing turtle bycatch (WWF, 2011).

For instance, in the Coral Triangle, this change has seen rates of turtle bycatch dropping by 80% (WWF, 2011)! That’s awesome news, but wait! The bigger picture is yet to be seen.

Digging deeper, I found that while benefiting turtles, circle hooks were actually more likely than J hooks to catch sharks (Gilman, 2016). Given their low reproduction rate and slow maturation, shark populations are particularly vulnerable to this threat (Ocean Portal, 2018). This goes to show that there’s no one-size-fits-all solution towards reducing (or dare I hope… towards eliminating?) bycatch – as it would be for all environmental issues – and nuances would have to be made for different fisheries.

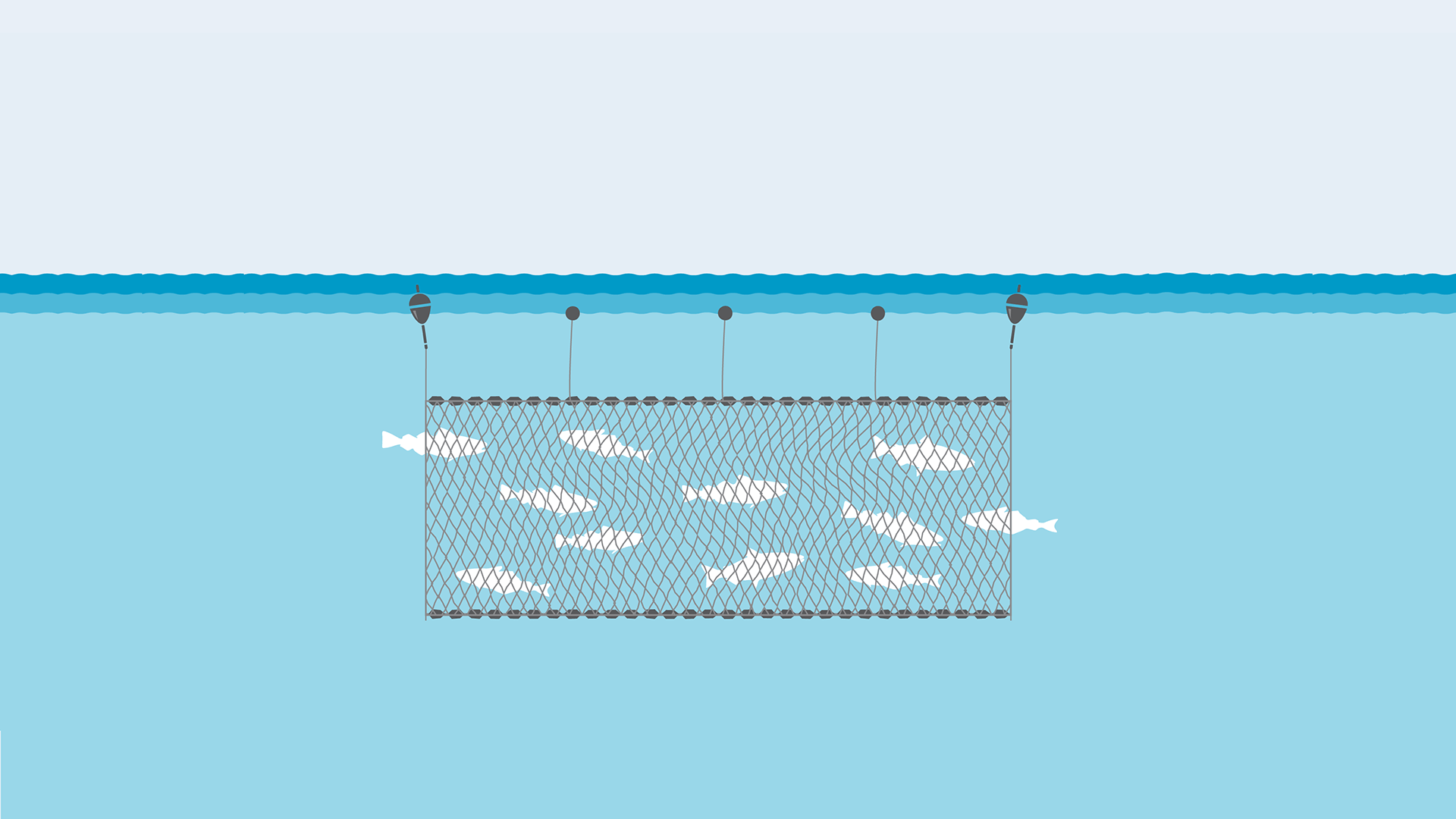

Moving on, nets are commonly employed in fishing, such as in seine fishing and trawling. But let’s look at driftnet fishing, in which huge nets are hung vertically underwater. With the nets being virtually undetectable, unsuspecting fish swim right into them and become hopelessly entangled. Driftnets are tremendously efficient in catching fish, given the low effort needed. Nevertheless, their non-selectivity leads to massive amounts of bycatch. The California Driftnet Fishery exemplifies the indiscriminate nature of driftnetting (Karpa, Steiner & Fugazzotto, 2015):

- For every 8 animals caught, only 1 is its targeted species – swordfish.

- Over the past ten years, close to 900 marine mammals were killed, including dolphins, whales and seals.

- 99% of blue sharks caught over the past ten years were discarded.

This is absolutely unacceptable, to me at least. For the sake of the marine ecosystem, such destructive fishing practices ought to be banned.

And indeed, in recognition of the detrimental effects of driftnetting, the UN banned the use of large driftnets (longer than 2.5km) in international waters in the early 1990s (L.A. Times, 1991). Over the years, more driftnetting regulations seem to be forming, such as the EU proposing in 2014 to forbid the usage of driftnets in their waters (EU, 2014), and since about a year ago, California has been set to prohibit commercial driftnetting (Green, 2018)! Surely that’s a step in the right direction, but really, I wonder how effective these regulations would be in improving the sustainability of our fishing practices? Stay tuned next week when I address this question!

Sea ya!

References:

EU. (2014, May 14). Fisheries: European Commission proposes full ban on driftnets. Retrieved fromhttps://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-14-563_en.htm

Gilman, E. (2016, May 9). Accounting for Conflicts between Species Groups. Retrieved from https://iss-foundation.org/mitigating-problematic-bycatch-in-tuna-fisheries/

Green, M. (2018, August 31). California passes bill to ban controversial drift net fishing. Retrieved from https://thehill.com/policy/energy-environment/404553-california-passes-bill-to-ban-controversial-driftnet-fishing

L.A. Times. (1991, Dec 21). “U.N. Adopts Global Drift-Net Ban.” Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-12-21-mn-624-story.html.

Karpa, D., Steiner, T., & Fugazzotto, P. (2015).California Driftnet Fishery: The True Costs of a 20th Century Fishery in the 21st Century. Retrieved from https://seaturtles.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Driftnet-Overview-Turtle-Island.pdf

Ocean Portal. (2018, December 20). Sharks. Retrieved from https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/sharks-rays/sharks

Swimmer, Y., Gutierrez, A., Bigelow, K., Barceló, C., Schroeder, B., Keene, K., Shattenkirk, K., & Foster, D. G. (2017). Sea Turtle Bycatch Mitigation in U.S. Longline Fisheries. Frontiers in Marine Science, 4. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2017.00260/full

WWF. (2011, Jan).Towards the Adoption of Circle Hooks to Reduce Fisheries Bycatch in the Coral Triangle Region.

greenmoviejunkie

September 24, 2019 — 3:26 pm

Hi Vera!

This post was really informative to me since I don’t know much about fishing methods. Thanks for bringing up the strengths and weaknesses of the methods! From what I am sensing, there seems to be a lot of regulations in place to ban or switch fishing methods that may impact the environment negatively. That’s great but are there also efforts to develop new fishing methods that minimize the chances of bycatch?

-Wei Qiang

vera

September 25, 2019 — 3:51 am

Hello Wei Qiang ~

To put it simply, I don’t think there have been new methods of fishing developed to reduce bycatch. At least that’s what I got from looking up online. I think there’s only so many ways you can catch fish in bulk – angling, netting, trapping, harpooning… But in finding out whether there are any new fishing methods, I discovered quite a few unique methods (not necessarily commercial ones)! In this video, catfishes were expelled out of the water holes as oil was dribbled in (it didn’t look like oil to me though… why are there bubbles haha). I was quite intrigued! I think the oil interfered with their breathing which caused them to flop out one by one. I also discovered that in Japan, cormorants are used in traditional fishing – a method called ukai! The birds are trained to dive and catch fish, and a snare is tied around their neck to prevent them from swallowing their catch. That sounds a bit dubious :/ I hope the birds aren’t harmed from this! You can read more here!

Thanks for reading my blog 😀

Vera

e0406393

September 25, 2019 — 9:01 am

Hi Vera,

I really liked the way you presented this blog post. I was just wondering if there are any reasons why commercial fishers might be deterred from or uninterested in adopting more sustainable fishing practices?

Cheers,

Elliott

vera

September 25, 2019 — 2:29 pm

Hello Elliott! Thanks for reading my blog 🙂

The way I see it, some commercial fishers aren’t that receptive to more sustainable fishing practices if it entails a change in their fishing gear since it could mean compromising their catch. After all, that’s their main concern (more catch = more profit!), and so it’s understandable for them to worry about the efficiency of the more sustainable fishing practices!

Check out this video on the switch to circle hooks in the Coral Triangle – some fishers expressed doubts on the capability of the circle hook in catching fish, worried that it would be inferior to the J hook. Happily enough, they came to accept it after trying it out themselves. From what was shown, these fishers needed that one push to try out the circle hook, which came in the forms of:

– Explanations by relevant authorities

– Hearsay from friends

– Observing trials that had been done elsewhere

This shows that it’s not that simple to get fishers to switch to more sustainable fishing practices. They want to maintain their volume of catch, so there needs to be evidence to convince them that these sustainable practices aren’t going to reduce it. For some sustainable fishing practices (I can’t think of any examples right now oops), the lack of trial-and-error and its results could reduce the confidence of commercial fishers in adopting them.

However, even with evidence to show that catch is not affected, there may still be resistance against the sustainable fishing practice in question. One such example would be the usage of turtle excluding devices (TEDs) in shrimp trawlers. TEDs are basically escape routes for turtles caught in trawl nets, so they won’t drown. Though proven to not reduce shrimp catch significantly, shrimpers still opposed to using the TEDs. Mainly, they argued that TEDs costed them to lose substantial profits – which is invalid because the catch is only reduced by a small margin, and even that can be overcome through accumulating experiences in using TEDs. So why else were the shrimpers so against TEDs? One reason could be due to the impersonal nature of the whole affair. There weren’t many one-on-one discussions going on between conservationists (TED supporters) and shrimpers, and that led to the rise of the “us vs them” divide. The shrimpers probably felt that the TED supporters had no care for their income (and the conservationists probably felt that the shrimpers were simply unreasonable), hence leading to the resistance against TEDs. You can read up more about this here! Actually, this reminds me of what we are learning in ENV1202 – communication really is key, and perhaps the best way to get people to understand your point of view would be to talk to them personally!

So, the uncertainty in the efficiency of sustainable fishing practices plus the ineffective (or sometimes lack of) communication in portraying their efficiency to fishers could be some factors deterring commercial fishers from making the switch!

Vera

Joanna L Coleman

September 28, 2019 — 6:30 am

Hi Elliott,

Vera did an AMAZING job replying to your question, so my addition isn’t meant to suggest she missed something. In fact, she conveyed relevant info I probably wouldn’t have known about otherwise.

But it occurred to me that another barrier is the fact that fishing vessels and gear cost a lot of money. I’m not sure, but I suspect it might be very expensive to retrofit a vessel that uses, say, purse seining, with an entirely new system. And if, as Vera points out, alternate gear types might reduce the landings and therefore profitability, the investment might take a really long time to pay for itself, and maybe it wouldn’t ever.

jc

Dennis

September 27, 2019 — 2:09 am

Hey Vera, your post made me wonder if Singapore has any laws regarding bycatch (if there is commercial fishing in our waters). Would you know anything about that and if so what do you think about them?

vera

September 27, 2019 — 5:22 am

Hey Dennis!

Unfortunately, I have ZERO clues on Singapore’s laws on bycatch. Googling didn’t seem to bring any information. I intend to visit our fishery ports to take a look at our fish imports though – perhaps I can find someone who’s willing to talk to me about this! (Both Ophelia and Sheryl already went down to Senoko Fishery Port and wrote about it in their blogs – I’m kinda excited to go down and see things with my own eyes :D)

Commercial fishing likely occurs within our Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), looking at the vessel tracking map that Global Fishing Watch has on their website.

While not really answering your question, I found something interesting! This 1977 study showed that in the mid-1970s, trawlers fishing at the Kangkar Fish Market (of course it’s closed now – it used to be located at the end of Upper Serangoon Road) had an average of 30% bycatch in their landings. Apparently, these undesirable fishes are termed ‘trash fish’, and consisted of immature fishes, commercially insignificant fishes and species that can’t be eaten (by humans at least). The authors attributed landings of immature fishes to small mesh sizes in the trawl nets. This is all new information, and reveals a nice bit of our history, doesn’t it? The market was known for selling fish wholesale 🙂

Vera

References

https://www.singaporememory.sg/contents/SMA-6c232073-c8ee-4792-9a43-9eb660a83e96

Dennis

October 1, 2019 — 2:42 am

Cool! Thanks for finding that 1977 study, I thought it was really interesting that such studies were done then, by the Japanese Society of Scientific Fishes no less. I wonder why there haven’t been any recent studies done.

I’m excited to read your blog on your trip down to Senoko!