Note: This report was originally written in end-March 2020 for the Luang Prabang Urban Development & Administration Authority. For this blog post, I have included some minor updates.

Background

My PhD research project, “Living in a watershed: the role of traditional and local practices”, aims to understand the traditional/local practices that are beneficial for the management of the watershed area of the Kuang Si Waterfall, as well as how these practices can be retained in the future. It uses a participatory action research approach whereby villagers co-identify debatable or contestable traditional/local practices and subsequently co-examine these practices through field experiments/data collection. This methodological approach not only recognises that a researcher’s relationship with the researched is bi-directional, but also legitimises my presence in the villages to do extended participant-observation in order to understand the daily lives of the villagers.

The two villages that I focussed on were Thapene village and Nong Khuay village, from May 2019 – May 2020[1]. This report describes the data collection at Thapene village. Ms Phonevilay Soukhy[2] assisted me with most of the fieldwork at Thapene village.

Introduction

In June 2019, a workshop (Figure 1) was conducted with several villagers of Thapene village, to gather inputs on how Thapene village manages upstream and downstream water resources. We also asked if there were any challenges with regards to water resources management that could benefit from a research process. Through another 3 trips to Thapene village to conduct participant-observation, discuss with key villagers and understand its drainage system, we decided to focus on the practice of waste management for keeping the watershed clean. This would help to raise awareness about Thapene village’s new challenges of (i) increasing waste from tourism and (ii) the non-biodegradability of plastic litter.

Much research in recent years has shown that plastic litter can harm animals and reduce agricultural productivity. However, because plastic takes a long time to biodegrade, it would accumulate in the environment. On e common option to get rid of plastic litter is to burn the plastic waste. This is a health hazard because burning plastic without a proper incinerator and a smoke-scrubber will release harmful dioxins. These chemicals can be inhaled or enter our waters and soil, causing cancer and birth defects in human beings. Dioxins also accumulates in the fatty tissues of animals, therefore passing on through the food chain from animals to human beings. In addition, there is ongoing research about the health hazards of micro-plastics: small particles of plastic that are produced when larger plastic pieces break apart. Across the globe, more than 95% of the plastics sent for recycling does not get recycled at all. Because 40% of plastic waste across the globe is single-use plastic, there is potential to decrease the amount of plastic waste that is produced in the first place by re-using as much as possible.

From on our conversations with the villagers, we learnt that Thapene village started a rubbish collection system in the 2000s. The two dumpsites (see Figure 2) were built with support from the Tourism Department. A village-operated rubbish collection truck collects the rubbish from the houses, shops, restaurants, guesthouses and the Kuang Si Waterfall Park. The rubbish is sent to the dumpsite(s) and burned about once a week, or whenever it is full (Figure 3). We also understand that a few villagers collect used metal cans and used plastic bottles to sell to collectors for 3,000LAK/kg and 1,000LAK/kg, respectively. Because the selling price is low, the work of collecting used plastic bottles is unattractive.

Figure 3: Residual smoke from the burning of rubbish at the Thapene village dumpsite, while the rubbish collector shovels the rubbish on this truck into the dumpsite (Photo: Y.S. Lau)

Hypothesis

The hypothesis that was identified was: “Tourism-related activities/services has led to more waste being produced in Thapene village.” To investigate this hypothesis, we would need to compare (i) the amount of rubbish from tourism-related activities/services with (ii) the amount of rubbish from households.

Methods

The initial plan was to set up litter traps along Thapene village’s streams. The litter traps would be set up to collect litter washed down from the sub-catchment of the area where tourism activities are conducted and the sub-catchment of the village’s residential area, respective. However, 2019 was an exceptionally dry year and the rainy season had ended by the time I was ready to collect data.

Hence, we decided to accompany the village’s rubbish collector to collect rubbish from the entire village. As the rubbish was collected, we weighed it using a weighing scale (Figure 4) and noted down whether it was from the houses or tourism-related activities/services (e.g. Kuang Si Waterfall Park, restaurants/shops serving visitors, guesthouses/hotels etc.) We also asked the rubbish collector when he last collected rubbish from each area, so that we could obtain the daily weight of rubbish. We also took photos to qualitatively assess the type of rubbish from each area.[3] The rubbish collection and weighing was done on 20 October 2019, 27 November 2019 and 6 January 2020.

As rubbish from the Kuang Si Waterfall Park is normally collected daily, we also asked the Park’s ticketing counter for the visitorship numbers on the date that the rubbish was generated. This would allow us to estimate the amount of rubbish produced per visitor per day in the Kuang Si Waterfall Park.

In addition, we also conducted interviews and house-to-house visits with more than 60 households in end-September 2019 to understand what kinds of traditional/local alternatives to plastic exist in Thapene village. During these interviews, we also informed the interviewees about the advantages and disadvantages of plastic.

Figure 4: While collecting rubbish from the village, we used a weighing scale to weigh the rubbish. (Photo: Y.S. Lau)

Figure 5: Sharing with villagers about the advantages and disadvantages of plastic (Photo: Y.S. Lau)

Findings

Based on the data collected, Thapene village produces about 600-1000 kg of rubbish per day (Table 1). Of this rubbish, 15-35% is from households, and 65% – 85% is from tourism-related services/activities.

We also found that within the Kuang Si Waterfall Park, each visitor generates about 0.14kg of rubbish (Table 2). This is almost equivalent to every 2 visitors leaving behind a full 300ml bottle of water for it to be cleared from the Park.

In addition, we observed that there was more organic waste in the rubbish from households, whereas we saw more single-use plastics (e.g. plastic bottles, foam plates/boxes, plastic straws, plastic bags) in the rubbish from the tourism-related services/activities (Figures 6 and 7). Overall, it was observed that about two-thirds of the rubbish is organic waste.

Since the Tourism Department helped to build Thapene village’s dumpsites in the 2000s, the use of plastic has increased. Plastic bags became more common in Thapene village around 1995, and were also used to re-package snacks into smaller quantities. Later, foam boxes, plastic straws and plastic cups became more common around 2010. Single-use chopsticks became more common around 2015. However, from our interviews and house-to-house visits, we found that there is still a culture of re-using plastic amongst the villagers. In addition, villagers and some businesses in Thapene village have alternatives to plastic in their daily lives/operations (Table 3). These should be given more recognition and promoted, if possible.

| Date of rubbish collection | Category | Source of rubbish | Weight of rubbish collected (kg) | Frequency of collection | Weight of rubbish produced per day (kg) |

| 20 / 10 / 2019 | Houses | Houses | 680.7 | Once a week | 97.2 |

| Sub-total

|

680.7 | 97.2 (17%) | |||

| Tourism-related services/activities | Kuang Si Waterfall Park | 130.1 | Daily | 130.1 | |

| Restaurants / shops | 269.0 | Daily | 269.0 | ||

| Restaurant KW | 52.6 | Daily | 52.6 | ||

| Restaurant TH | 39.2 | Weekly | 5.6 | ||

| Private carpark / shops | 186.0 | Weekly | 26.6 | ||

| Guesthouse | 8.2 | Weekly | 1.2 | ||

| Sub-total

|

685.1 | 485.0 (83%) | |||

| Total

|

1365.8 | 582.3 (100%) | |||

| 6 / 1 / 2020 (and 27 / 11 / 2019[4]) | Houses | Houses | 756.0 | Once in 2 days[5] | 378.0 |

| Sub-total

|

756.0 | 378.0 (34%) | |||

| Tourism-related services/activities | Kuang Si Waterfall Park | 263.8 | Once in 2 days[6] | 131.9 | |

| Restaurants / shops / private parking area / Business | 836.2 | Once in 2 days[7] | 418.1 | ||

| Restaurant CD | 152.0 | Once in 3 days | 50.7 | ||

| Restaurants / shops | 152.4 | Once in 2-3 days | 61.0 | ||

| Restaurant KW[8] | 115.4 | 3 times per week | 49.5 | ||

| Hotel V[9] | 50.4 | Once in 2 days | 25.2 | ||

| Sub-total

|

1570.2 | 736.3 (66%) | |||

| Total

|

2326.2 | 1114.3 (100%) | |||

| Table 1: Amount of rubbish collected from Thapene village | |||||

| Date | Amount of rubbish (kg) | Number of visitors | Amount of rubbish per visitor (kg per person) | Remarks |

| 19 / 10 / 2019 | 130.1 | 860 | 0.15 | The ticket office provided the ticketing revenue, from which the number of visitors is estimated[10] |

| 4-5 / 1 / 2020 | 263.8 | 2070 | 0.13 | The ticket office provided the number of visitors is provided |

| Table 2: Amount of rubbish per visitor at Kuang Si Waterfall Park | ||||

| Households:

• Banana leaves as wrapper • Eat food from nature • Bamboo sticks • Rope made from mulberry tree • Bamboo baskets • Bamboo strips for tying • Bags made from sacks • Plastic containers • Metal bottles • Fabric bag

|

Businesses:

• Recognise that reducing the amount of waste that is produced benefits themselves (e.g. Spring Water Cave Restaurant is too far away from the village’s rubbish collection system; spend a lot of time on cleaning) • Grow their own ingredients instead of buying from the market • Encourage people to dine-in • For takeaway: using alternatives to foam packaging – banana leaves, teak boxes, palm leaf boxes, coconut husks • Using banana leaves and plates made from bamboo – biodegradable • Using bamboo straws instead of plastic straws • When shopping for ingredients, encourage their staff to use basket instead of plastic bags • Offer reusable chopsticks as an option to customers instead of only single-use chopsticks |

| Table 3: Some examples of Thapene villagers’ alternatives to plastic use that help to reduce the amount of rubbish produced | |

Figure 6: Rubbish from the tourism-related services/activities. (Photo: Y.S. Lau)

Recommendations

To reduce the amount of rubbish sent to the dumpsite, Thapene villagers can make compost using organic waste and reduce the amount of plastic used. To do these, villagers need to be aware about how long each material takes to biodegrade.

Households and landowners can use organic food waste or horticultural waste to make compost or mulch. This will help to enrich the soil. They can also buy oil, shampoo and other daily necessities in larger quantities or in refillable bottles, to reduce the amount of single-use packaging.

Tourism and businesses can provide water refill stations instead of single-use plastic water bottles to their guests/customers. If possible, they should provide plastic bags and plastic straws only when people ask for them. They should also separate organic waste from inorganic waste so that the former can be used to make compost or garden mulch. Visitors should be reminded to throw away their rubbish properly to reduce the amount of litter.

Other partners (government, potential investors, businesses etc.) could provide financial assistance to subsidise the cost of biodegradable packaging, as a replacement to foam packaging. Some support could be provided to Thapene village to reduce incidental littering from the current waste management system. Examples of such incidental littering are: rubbish falling out of the rubbish collection truck when it travels on a bumpy road, and wind blowing rubbish out of rubbish bins. These could be addressed by, respectively, having a closed-top truck instead of an open-top truck, and having covers for rubbish bins. Looking upstream in the chain of production, product manufacturers should look into reducing packaging waste. Finally, as Thapene village is located about 1 hour from Luang Prabang city, villagers may not know about the latest ideas in minimising waste. Partners and friends should continually share ideas with Thapene village so that villagers are aware of possible options and feel part of the wider collective effort to reduce waste.

Knowledge dissemination

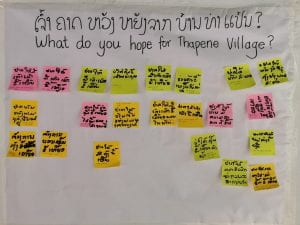

As part of the process of my PhD research, an exhibition about waste management at the meeting house of Thapene village was organised on 12-13 March 2020 to communicate the findings from my fieldwork at Thapene village. Villagers and students from the Thapene village primary school attended the exhibition (Figures 8, 9 and 10). In addition to reading the poster exhibits, they also took part in 2 simple quizzes about how long each material takes to biodegrade and why we should reduce the use of plastic. Because an earlier feedback was that villagers lacked reusable bags as an alternative to plastic bags, exhibition participants were also given reusable cotton bags which they customised through their own painting.

A workshop with was also organised on 12 March 2020 to discuss how to put possible solutions into action (Figure 11). It was attended by about 10 key villagers and two government staff from the Luang Prabang Urban Development & Administration Authority. The workshop revealed a keenness from villagers to address the issue of waste management at Thapene village. However, they need help from the government, such as through networking[11] and policy levers[12] to channel resources for addressing the issue, and to provide organisational legitimacy for initiating new programmes[13]. In addition, the key villagers pragmatically emphasised that any new programme will be self-sustainable only if there is a business case for it. The government staff shared that there is high-level political attention on the issue of waste management nationwide, and advised villagers to be specific when asking for help from external parties. They also encouraged the villagers to form small associations to make compost or biodegradable boxes for sale. Compared to other villages, the presence of the Kuang Si Waterfall is Thapene village’s geographic advantage.

Figure 9: Villagers write down what they hope for Thapene village after viewing the poster exhibits (Photo: Y.S. Lau)

Figure 11: Workshop with key villagers and government staff on 12 March 2020 (Photo: Sot Phetsamone)

Conclusion

Based on the above findings, the hypothesis that “Tourism-related activities/service has led to more waste being produced in Thapene village” holds. While tourism has helped villagers in Thapene village to improve their livelihoods, it has also introduced more rubbish – including plastic waste – into Thapene village. This rubbish is currently burned at the nearby dumpsite, and the chemicals released will be harmful to villagers and the environment. Improvements to the current rubbish collection system are needed.

However, as Thapene village develops/modernises, the use of plastic will become more pervasive in the village. This needs to be managed, such as through constant environmental campaigns to remind villagers about the disadvantages of plastic and through programmes to reinforce villagers’ traditional/local practices that are alternatives to using plastic. Villagers can also use organic waste to make compost or mulch, reducing the amount of rubbish that goes to landfill while enriching their soil.

Globally, the problem of waste management reflects mankind’s reluctance to conserve resources and take care of nature. Waste management is made even more complicated due to the presence of plastics in the waste-stream: while plastic makes our lives more convenient, it is also very difficult to manage as rubbish. We hope that villagers at Thapene village, government staff and other stakeholders can carry on the momentum from the exhibition to generate less rubbish, so that Thapene village can be a model for other villages in Laos and beyond.

Acknowledgements

My fieldwork at Thapene village would not have been possible without the assistance of Ms Phonevilay Souky, who displayed passion, strength and patient determination. She was literally willing to “get her hands dirty” and translated most of the materials for Thapene village.

Many thanks to Mr Oudom Soulimoungkhoun, Ms Sot Phetsamone and Mr Siphanh Daovongdeuan for their assistance in the various phases of my fieldwork at Thapene village. I would also like to thank Mr Phonthip Phongsavath and Mr Viengphet Panoudom of CHESH-Lao for their important behind-the-scenes support. Much appreciation also goes to the village leader and key villagers for hosting me during our numerous visits to Thapene village.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge CHESH-Lao/SPERI for hosting me in Laos, the National Geographic Society for the funding support, my PhD thesis committee for providing intellectual critique, and my family for the invaluable the moral support. Without your trust, support, feedback and understanding, I would not be able to conduct my fieldwork in Laos.

====

[1] Originally supposed to be until April 2020. See my other blog post about my fieldwork against the backdrop of covid-19 in Laos.

[2] From the Northern Agriculture & Forestry College, Luangprabang province

[3] There was a suggestion to separate the rubbish as part of the analysis. However, this would pose a safety and hygiene concerns, because items such as used toilet paper and rotting food/organic waste were part of the rubbish.

[4] There was supposed to be a village-wide collection of rubbish on 27 November 2019. However, the rubbish truck broke down mid-way. Hence, data from 27 November 2019 is used to supplement the gaps in the data collected on 6 January 2020.

[5] The frequency might actually be lower for some houses that are farther away from the main road because we understand that it is difficult for the rubbish collector to access these houses.

[6] The frequency of rubbish collection is supposed to be daily at the Kuang Si Waterfall Park. However, because of a change in rubbish collector on 5-6 January 2020, two-days’ worth of rubbish was collected on 6 January 2020.

[7] In reality, the frequency might be lower, because we saw that the rubbish from one shop was teeming with maggots.

[8] Data from 27 November 2019. Rubbish was not collected from this location on 6 January 2020.

[9] Data from 27 November 2019. Rubbish was not collected from this location on 6 January 2020.

[10] The number of visitors is estimated based on the ticket revenue of 15,000,000 LAK on 19/10/2019. Each ticket costs 20,000 LAK for a foreigner and 10,000 LAK for locals. Based on observations, we assume that at least 75% of visitors are foreigners. If the proportion of foreigners is actually higher, the number of visitors decreases and so the amount of rubbish-per-visitor increases.

[11] For example, the government is aware of support programmes that villagers are not aware of.

[12] For example, the government, which processes the permits for new businesses in Thapene village, could institute a requirement for applicants to contribute towards addressing the issue of waste management in Thapene village.

[13] A key villager fed back that sometimes it is easier to organise the villagers if there is an external party initiating the programme/initiative.

Recent Comments