Abstract

Involving rural communities in nature conservation is important for tackling the biodiversity loss and environmental degradation in Southeast Asia. Using iNaturalist as a platform, a BioBlitz event was organised at the Human Ecology Practical Area (HEPA) in Ha Tinh province on 2-3 January 2021 with the dual objectives of (1) kickstarting the systematic documentation of local species diversity in the restored forest environment and (2) engaging the local community in nature education. The BioBlitz@HEPA event involved a total of 63 participants (students, educators, officials and local area support staff) from Son Kim 1 commune and 12 volunteer organisers from HEPA, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. 103 observations were uploaded onto iNaturalist and, with the crowdsourced contribution of taxonomic identifiers around the world, 12 species have been preliminarily identified as of August 2021. The event increased students’ appreciation about nature, exposed educators to a more effective pedagogy and made all those involved more enthusiastic about Vietnam’s nature. As rural communities live near natural resources and hence are at the frontlines of nature conservation, it is important to continue investing in environmental and nature education programmes to strengthen their motivation to protect the nature that is right at their backyard.

Keywords:

- biodiversity

- rural community

- iNaturalist

- citizen science

- nature conservation

Authors:

Yingshan LAU1, Thi Hoai Thu NGUYEN2, Carlos G. VELAZCO-MACÍAS3, To Kien DANG4, Van Vin LOC5, Lien PHAM6, Thi My Hoa NGUYEN76, Thi Lan DUONG8, Thanh Tung PHAN9

1Department of Geography, National University of Singapore (lau_ying_shan@u.nus.edu)

2Human Ecology Practical Area (HEPA)

3Citizen Science Team, National Geographic Society

4Community Entrepreneur Development Institute (CENDI)

5Human Ecology Practical Area (HEPA)

6Saigon Outdoor Kids

7Son Kim 1 Primary School

8Son Kim Secondary School

9Son Kim 1 Commune People’s Committee

Introduction

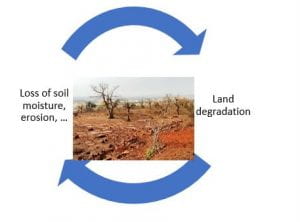

Southeast Asia is a region with high risk of animals becoming extinct, due to factors such as poverty, inadequate infrastructure, weak governance of protected areas and uncontrolled wildlife trade (Sodhi et al, 2004; Duckworth et al, 2012). Being located in remote areas, rural communities are at the frontlines of conservation, yet they tend to lack access to opportunities and resources for environmental conservation (Neudert et al, 2016; Mendez-Lopez et al, 2017; Chiutsi and Saarinen, 2017). The most effective form of environmental conservation starts from the heart: a values-driven ethic about their relationship with nature, inculcated through realising the wonders of nature, e.g. the various flora and fauna, or the ecosystem services (Washington, 2018).

The engagement of rural communities via citizen science can increase awareness, knowledge and appreciation about the biodiversity in remote areas. While there lacks consensus about what citizen science specifically is (Aristeidou, 2021), it can be understood as “the practice of public participation and collaboration in scientific research to increase scientific knowledge” in which “people share and contribute to data monitoring and collection programmes” (NGS, 2021a). Benefits include allowing public participation in science and informally improving the scientific knowledge of volunteers (Aristeidou, 2021). Citizen science combines public education with research, and the resultant environmental data generates publicly-available information that informs global biodiversity conservation, monitoring, and planetary stewardship (Dickinson et al, 2012; Chandler et al, 2017). When designed with citizen science approaches in mind, nature appreciation events targeted at rural communities are platforms for knowledge-transfer, capacity-building, documentation and reinforcement of our motivation for environmental conservation.

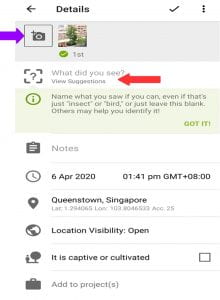

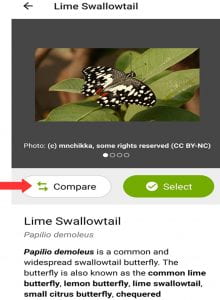

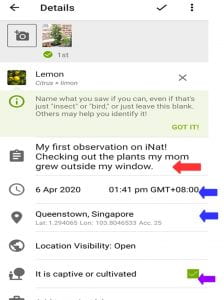

The growing pervasiveness of digital technology and network connectivity in rural areas enables citizen science. One such tool to promote nature appreciation is the iNaturalist platform, a joint initiative of the California Academy of Sciences and the National Geographic Society (iNaturalist, 2021a). Founded in 2008, iNaturalist allows the public to easily document biodiversity by making observations of organisms around them via taking photos or audio recordings (Nugent, 2018). Examples of the uses of iNaturalist has included: engaging first-year undergraduate biology students in outdoor laboratories in the USA (Unger et al, 2020) and, more recently, to document sightings of large mammals in urban centres during periods of restricted human activity arising from the Covid-19 pandemic (Vardi et al, 2021). BioBlitzes are events that bring together scientists, students, educators and community members to find and identify as many species as possible in a specific area over a short period of time, and they make use of iNaturalist to accelerate citizen science (NGS, 2021b).

Most citizen science programmes are in Europe, North America, South Africa, India and Australia (Chandler et al, 2017), so BioBlitz@HEPA is unique in that it was held in Vietnam. This was a BioBlitz event that was conducted at the Human Ecology Practical Area (HEPA) on 2-3 January, involving a total of 42 primary and secondary school students as well as other local stakeholders in the rural community of Son Kim 1 commune, Ha Tinh province. In addition to being a nature appreciation activity, it kickstarted the systematic record of species diversity in HEPA through the use of iNaturalist. This paper shares how BioBlitz@HEPA was organised, the biodiversity that was observed during the event and the feedback from the participants.

Methods

-

Study site

BioBlitz@HEPA took place in the Human Ecology Practical Area (HEPA), a forest protection area (approximately 18°26’N, 105°11’E) in Son Kim 1 commune, Huong Son district, Ha Tinh province (HEPA, 2021). HEPA is a 500-ha forest site located in Central Vietnam and within the Northern Annamites tropical rainforest region. HEPA’s forest has been restored from a heavily-logged site over the last 19 years (2002-2021), thanks to the enormous and persistent reforestation and protection efforts of a small group of civil society. Over the years, there have been observations of many animal species returning to HEPA, but there has not been an opportunity to systematically document these. Moreover, it has been the more affluent city-folk who have attended HEPA’s environmental workshops and nature retreats. Hence, BioBlitz@HEPA was an exceptional opportunity to contribute species data in a lesser-studied area, and to inculcate motivation for environmental conservation amongst the rural community.

-

Organising BioBlitz@HEPA

BioBlitz@HEPA took place on 2-3 January 2020. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the organisation took over a year and required a lot of perseverance and negotiation with the Son Kim 1 local commune authorities. Well-formed plans were postponed twice and then reactivated at the eleventh hour as restrictions on domestic travel were imposed and then eased. It was initially planned that volunteers experienced in nature guiding and knowledge in biodiversity would travel from Singapore, but in light of the growing contagion and its impact on international travel, the plan had to be changed. A series of online training sessions were conducted so that a team of about seven volunteers from Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) and HEPA (i.e. the Vietnam planning team) could lead the event instead. The online training sessions covered (1) the use of iNaturalist by the iNaturalist coordinator from Mexico and (2) the specific methods for conducting nature surveys by the Singaporean project lead, e.g. kick-sampling and line transects.

Considering that the event was planned for primary and secondary school students, safety was of the utmost priority and many stakeholders were involved in planning the event. The Vietnam planning team sought permission from the District Education Department of Huong Son district and relevant agencies. Representatives of Son Kim 1 commune discussed with the youth union, local police, and clinical units to ensure participants’ safety. The Vietnam planning team also chose sites within HEPA that were suitable for the experiential learning objectives of encountering biodiversity in a fun and engaging manner, and which were also safe for the young students.

Table 1 summaries the total number of participants in the BioBlitz event on 2-3 January 2021.The participant students were nominated by their respective schools based on their good academic performance in Biology, their confidence in speaking and sharing, their ability to understand English and their good behaviour. Volunteers from HEPA, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City took on the role as of organisers: experts, guides, facilitators and photographers. In line with HEPA’s ethos of “teaching by learning and learning by doing”, these volunteer organisers also learnt about the biodiversity in HEPA and nature conservation issues through their involvement in the event.

Table 1: List of people involved in the BioBlitz@HEPA on 2-3 January 2021.

| Role in BioBlitz@HEPA |

Category |

Number of people |

| 2 January 2021 |

3 January 2020 |

| Participants |

Students |

21

(Son Kim 1 Primary School;

Grades 4 and 5) |

21

(Son Kim Secondary School;

Grade 7) |

| Educators |

7

(Son Kim 1 Primary School) |

4

(Son Kim Secondary School) |

| Officials

(Commune People’s Committee) |

3 |

| Local area support staff

(rangers, doctors (for first-aid support), drivers, cooks) |

7 |

| Organisers |

Volunteers

(experts, guides, facilitators and photographers) |

12 |

-

The BioBlitz@HEPA event programme

In planning BioBlitz@HEPA as a fun and engaging nature appreciation event for students, three learning objectives were identified: (i) To develop in children a sense of awe/fascination for nature, (ii) To understand that different habitats are home to different flora/fauna, and (iii) To know the importance of forest conservation.

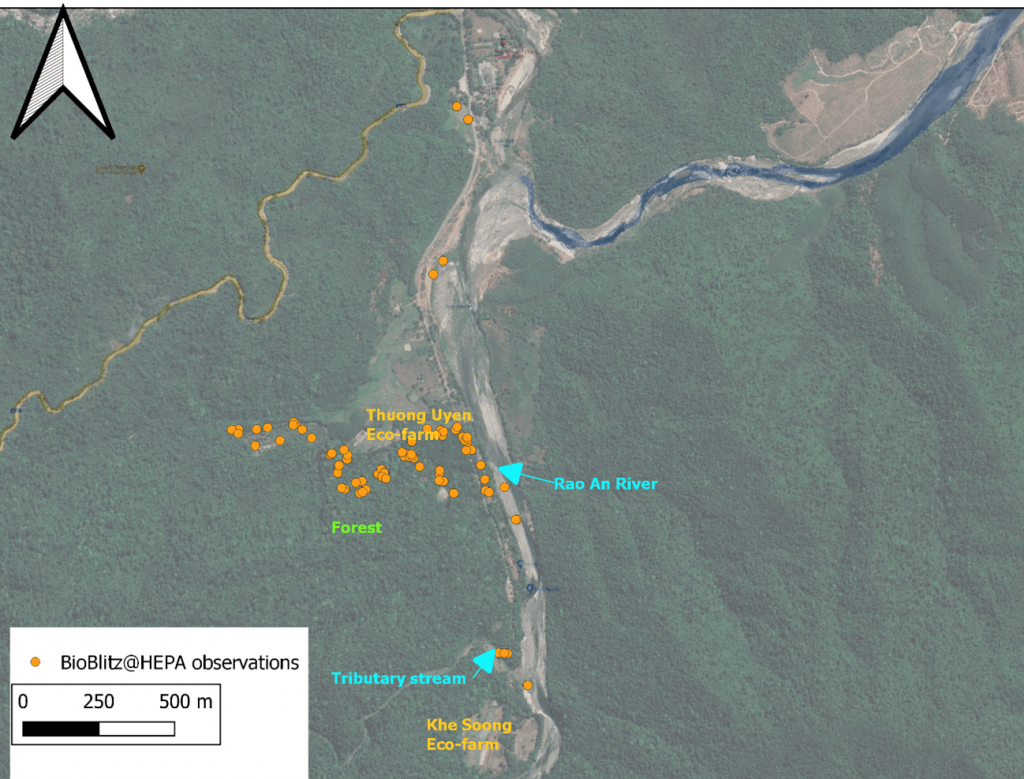

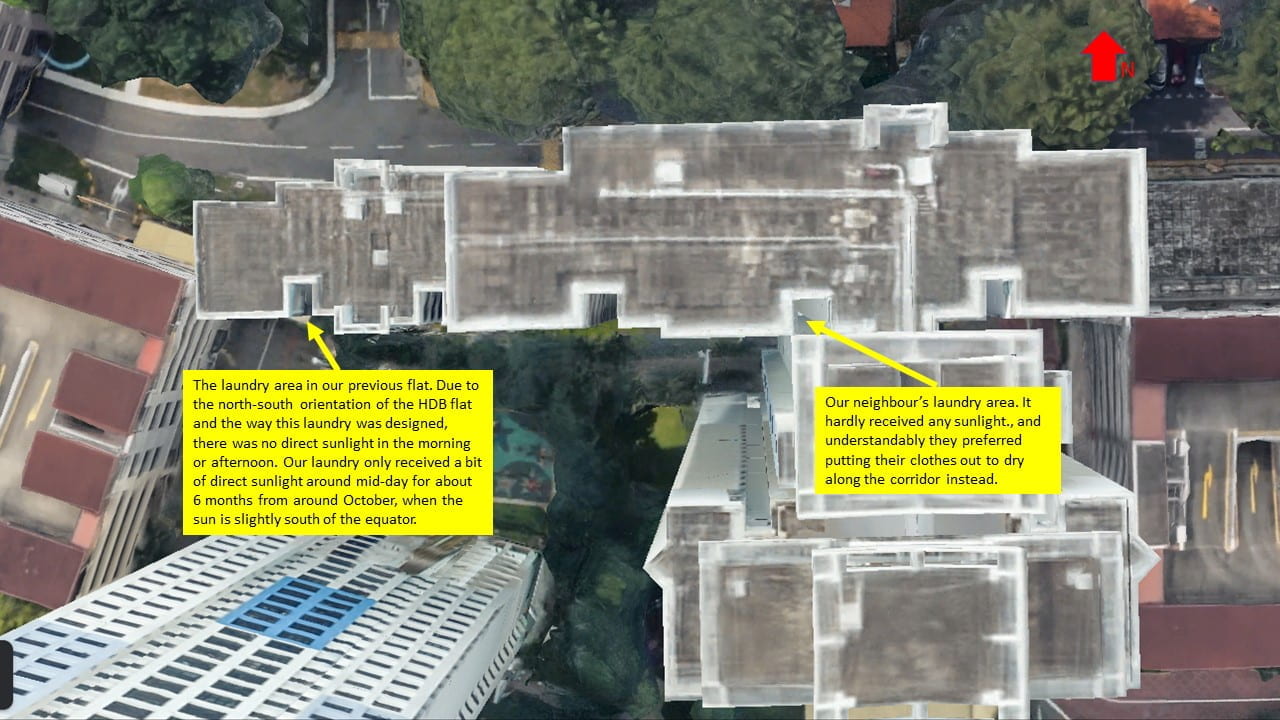

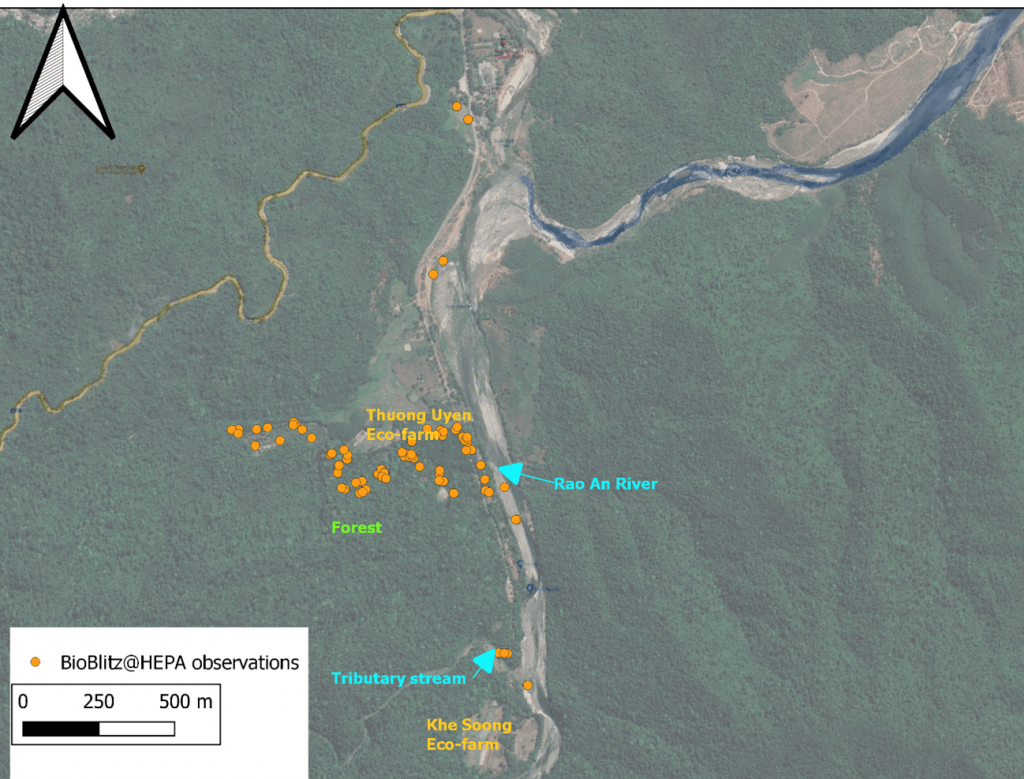

For each day, participants were divided into two large groups of about 16-17 persons (about 10 students) per group. After the morning’s briefing and introductions, students were guided to the various sites in HEPA. The local guides and the biology teachers from the schools gave explanations to the students along the way (Figure 1), such as the role of forests, the importance of conservation actions and the long-term forest protection work done in HEPA, while the students took photographs of their observations (Figure 2). Three different habitats were covered: freshwater, eco-farm and forest (Figures 3, 4 and 5). Figure 6 shows the locations of the respective habitats. The freshwater habitat was represented by the Rao An River and its tributary stream. The eco-farm habitat was represented by HEPA’s Khe Soong Farm and Thuong Uyen Farm. The forest site was along the paths leading to Khe Soong Farm, on the rocky roads leading to Cay Khe Farm and, for the Grade 7 students to explore further, along the inner route behind Linh Moc Farm. Emphasis was given to wild organisms, i.e. those not cultivated and reared by humans. At the river, the groups adopted a ‘kick-sampling’ method (TAF, 2017). At the eco-farms and in the forest, the groups adopted a ‘line transect’ method (BBC, 2021). Learning points and discussion questions, summarised in Table 2, were offered at ‘teachable moments’ during the BioBlitz nature guiding. A general ethos of “Take nothing but pictures, leave nothing but footprints” was adopted at all sites to remind participants to collect all their belongings and make sure there is no litter, emphasising the need to respect nature. In the afternoon, there were talks on the importance of biodiversity and on the local conservation efforts in Vietnam. This included a short English presentation from Singapore via Skype, which was translated to Vietnamese by the facilitators and three students.

Figure 1: A local guides providing explanation to the students along the forest route. (Photo credit: HEPA)

Figure 2: Students took photographs of their observations. (Photo credit: HEPA)

Figure 3: BioBlitz@HEPA participants at the Rao An River, a freshwater habitat. (Photo credit: HEPA)

Figure 4: Khe Soong Farm, an eco-farm habitat. (Photo credit: HEPA)

Figure 5: The HEPA forest. (Photo credit: HEPA)

Figure 6: Map showing the locations of the freshwater habitats, the eco-farm habitats, the forest habitat in HEPA (approximately 18°26’N, 105°11’E) as well as the iNaturalist observations from BioBlitz@HEPA. (Source: Authors, using iNaturalist (2021b) overlaid onto Google Satellite base map.)

Table 2: Learning points and reflection questions, leveraging on teachable moments that could occur in each habitat.

| Habitat |

Learning points |

Reflection questions |

| Freshwater |

· At locations with lower streamwater velocity and more sediments, there are more diversity of species, because (i) there are more nutrients for food and (ii) it is a better/safer resting place.

· Some water bugs are good at camouflage: evolved to hide in nature… predator-prey relationship… |

Will these animals still exist without the forest around the stream? |

| Eco-farm |

· Even in a human-modified landscape like a farm, there are wild organisms hiding in the corners…

· Some animals are good at camouflage: evolved to hide in nature… predator-prey relationship…

· Relationships in ecosystems includes humans e.g. snakes eat rats that destroy crops; making organic compost attracts worms that aerate the soil |

Will these animals/plants still exist if heavy doses of pesticides/herbicides are used? |

| Forest |

· Greater diversity of organisms in less-disturbed/less-modified areas…

· Some animals are good at camouflage: evolved to hide in nature… predator-prey relationship…

· Be quiet to listen for bird calls: to observe nature well, we need to quieten ourselves…

· Non-timber forest products (NTFP) value of species e.g. herbal plants for medicine; trees for timber; mushrooms for food: (i) forest ecosystems are important for humans too (ii) some of these NTFPs can only grow in forests because they need shade or unique growing conditions |

Will these animals/plants still exist without the forest? |

Assessment of the participants’ learning were through group presentations and interviews. Over the two days, eight group presentations were made by the students in the afternoon. The students shared what they had observed during the morning’s guided field trip. Interviews were conducted with six students and two teachers and recorded on video, with informed consent. The interview questions for the students were: “What did you see today?”; “What did you learn today about nature?”; and “What should you do to protect the environment and biodiversity?” The interview questions for the teachers included: “What are your thoughts about the BioBlitz@HEPA programme?”; and “How does this relate to what students learn in school about Biology?” Insights to the participants’ learning were also gleaned from the organisers’ interactions with them, e.g. conversations during breaks and over the campfire.

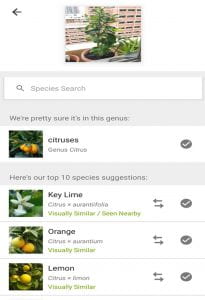

After the event, the geo-tagged photo observations were uploaded onto iNaturalist by the teachers and the organisers. The image recognition algorithm on the iNaturalist platform suggested a preliminary species identification of these observations, and taxonomic identifiers from around the world went through these observations to confirm them. When two or more identifiers agreed on the species, the observation was considered ‘research-grade’ and became part of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, an open-source database used by scientists and policy makers around the world (GBIF, 2021).

Results

-

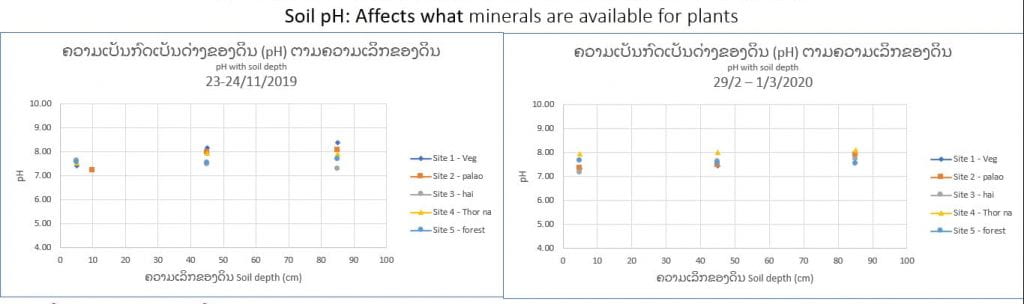

A preliminary biodiversity database for HEPA

From BioBlitz@HEPA, there were a total of 103 observations.[1] As of August 2021, 31 citizen-science taxonomic identifiers from around the world helped to identify the species in the observations, and 11 observations were research grade. As the uploaded observations were geotagged, the geographical distribution of the observations is also accessible on iNaturalist project webpage (https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/hepa-bioblitz-2020-nat-geo and Figure 6) (iNaturalist, 2021b). About 15% of the observations could be identified up to the species level, from which there were 12 distinct species. Examples of observations from the freshwater habitat are: green algae Chlorophyta, frogs/toads Anura and crabs Brachyura (Figure 7). Examples from the forest and eco-farm habitats are: splitgill mushrooms Schizophyllum commune, Elephant’s Foot Elephantopus mollis and Asian House Gecko Hemidactylus frenatus (Figure 8). Table 3 provides a summary of the observations.

Figure 7: Observations of flora and fauna at the freshwater habitat. (Source: iNaturalist, 2021b)

Figure 8: Observations of flora and fauna at the eco-farm and forest habitats. (Source: iNaturalist, 2021b)

Table 3: List of observations from BioBlitz@HEPA and their taxonomic rank.

|

Scientific name |

Taxonomic rank |

Number of observations |

| 1 |

Acmella |

Genus |

1 |

| 2 |

Agaricales |

order |

2 |

| 3 |

Agaricomycetes |

class |

4 |

| 4 |

Amauroderma |

genus |

1 |

| 5 |

Amphibia |

class |

1 |

| 6 |

Angiospermae |

phylum / division |

1 |

| 7 |

Animalia |

kingdom |

1 |

| 8 |

Anura |

order |

1 |

| 9 |

Araceae |

family |

2 |

| 10 |

Aralia |

Genus |

1 |

| 11 |

Araliaceae |

family |

1 |

| 12 |

Asteraceae |

family |

1 |

| 13 |

Bambusoideae |

family |

1 |

| 14 |

Brachyura |

order |

1 |

| 15 |

Camellia |

Genus |

1 |

| 16 |

Chlorophyta |

phylum / division |

3 |

| 17 |

Cocoseae |

family |

1 |

| 18 |

Codiaeum variegatum |

species |

1 |

| 19 |

Coffea arabica |

species |

1 |

| 20 |

Coleoptera |

order |

1 |

| 21 |

Dichomeris flavocostella |

species |

1 |

| 22 |

Echthromorpha |

genus |

1 |

| 23 |

Elephantopus mollis |

species |

1 |

| 24 |

Ephemeroptera |

order |

1 |

| 25 |

Eupatorieae |

family |

1 |

| 26 |

Fagaceae |

family |

1 |

| 27 |

Fungi |

kingdom |

2 |

| 28 |

Gastropoda |

class |

2 |

| 29 |

Hemidactylus frenatus |

species |

1 |

| 30 |

Heteropoda |

Genus |

1 |

| 31 |

Ichneumonidae |

family |

1 |

| 32 |

Insecta |

class |

2 |

| 33 |

Laccaria |

Genus |

2 |

| 34 |

Libnotes |

Genus |

1 |

| 35 |

Magnoliopsida |

class |

12 |

| 36 |

Megaloptera |

order |

1 |

| 37 |

Microporus |

genus |

2 |

| 38 |

Microporus xanthopus |

species |

2 |

| 39 |

Mimosa |

genus |

1 |

| 40 |

Mimosoideae |

family |

2 |

| 41 |

Muscidae |

family |

1 |

| 42 |

Nephrolepis |

genus |

1 |

| 43 |

Noctuoidea |

family |

1 |

| 44 |

Nyctemera adversata |

species |

1 |

| 45 |

Opiliones |

order |

1 |

| 46 |

Persicaria chinensis |

species |

2 |

| 47 |

Phanera championii |

species |

1 |

| 48 |

Phaonia |

genus |

1 |

| 49 |

Plantae |

kingdom |

9 |

| 50 |

Polypodiopsida |

phylum / division |

2 |

| 51 |

Polyporaceae |

family |

2 |

| 52 |

Polyporales |

phylum / division |

1 |

| 53 |

Rubus |

genus |

1 |

| 54 |

Schizophyllum commune |

species |

3 |

| 55 |

Stromanthe |

genus |

1 |

| 56 |

Synedrella nodiflora |

species |

1 |

| 57 |

Thelypteridaceae |

family |

1 |

| 58 |

Tracheophyta |

phylum / division |

1 |

| 59 |

Trametes coccinea |

species |

1 |

| 60 |

Trichilia |

genus |

1 |

| 61 |

Zingiberaceae |

family |

3 |

| 62 |

Zingiberales |

order |

2 |

| Number of identified species: |

12 |

| Total number of observations: |

103 |

[1] Excluding four observations of ‘Homo sapiens’ and five non-useable observations (e.g. blur or non-specific).

-

Students: increased appreciation about nature

For many students, it was their first time venturing into the forest. They were very excited and curious, with many questions for the facilitators. From the organisers’ interactions with the students, the students expressed that they wanted return to HEPA in the summer. With their field observations uploaded on iNaturalist and hence made available to the global community, they felt proud and more confident of their work.

During the group presentations, they shared that they became highly aware of the importance of nature in providing them with a safe place to play and to live. For example, they developed a better understanding of the relationships between trees, animals, insects, bacteria, fungi and the environment. They also expressed their commitment to take action in daily activities to protect biodiversity and nature and to encourage their friends and family to protect the environment.

A student from Son Kim 1 Primary School said during the interview:

“Today when we went to the river, I saw the fishes, fish and frog eggs; I also saw the different shades of rocks, stones – they are very nice. This afternoon we visited the forest: I saw Lim trees, a forest chicken, insects and spiders.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Male student from Son Kim 1 Primary School (translated from Vietnamese)

Beyond specifying what they observed, students from Son Kim Secondary School expressed the importance of nature in terms of how human beings are dependent on it:

“I learnt a lot of things today: the diversity of nature around us. After the trip, I know that nature has an important place in our lives. It provides us with food, clothes, drinks and clean air.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Female student from Son Kim Secondary School

“Today, I learnt a lot of things about nature and the importance of nature. As we know, nature is an essential part of our lives. It provides food, drink, clean air, and it helps human beings, animals and other living beings to grow and develop naturally.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Female student from Son Kim Secondary School

The interviewees expressed the need to protect nature:

“We must not destroy the trees, the environment; and need to protect nature, the forest, and plant more trees, protect the environment, and take care of our planet for a beautiful life.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Male student from Son Kim 1 Primary School (translated from Vietnamese)

“Today, nature is being destroyed. A lot of trees are cut. The water we drink everyday is polluted. So we must learn to protect nature. We must learn not to throw rubbish everywhere; tell everyone that we must protect, and the importance of, nature.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Female student from Son Kim Secondary School

“We should [keep nature clean] and reduce the amount of waste [generated] and many other single[-use] waste.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Female student from Son Kim Secondary School

-

Educators: a more effective pedagogy

The teachers were happy to witness that enjoying nature provides an immense opportunity for students to learn and develop. Their students were able to directly see and touch the flora and fauna, which the experts concurrently explained about. Pedagogically, organizing such outdoor lessons as experiential learning enables students to learn more effectively than instruction in the classroom (Son Kim 1 commune, 2021). They fed back that the event was effective in getting people to engage with and enjoy the real world through the use of iNaturalist.

“Through this outdoor activity, students have learnt and understood about the biodiversity that surrounds us. In the school, students [have] already learnt this topic but it is in theory and separately in each small topic. However, via today’s outdoor activity, students learnt lots of new things from the diverse knowledges in biodiversity to the methodology by [the organisers] from HEPA, Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi and Singapore. Students are confident to observe fauna and flora in the HEPA forest, from these activities they can understand more about the theories which they learnt from the school.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Teacher from Son Kim 1 Primary School (translated from Vietnamese)

-

Other stakeholders: increased enthusiasm about Vietnam’s nature

The Son Kim 1 commune government was proud that HEPA hosted this BioBlitz event. The local police, who oversees the Vietnamese-Lao border, learnt a new way of educating people about forest protection. The volunteers from Hanoi and HCMC were spellbound by the forest’s beauty and impressed by the collaboration from the local teachers and the local government. The commune Vice-Chairman added that he would like to replicate the event for more people in the commune. All participants enjoyed learning about nature and would like the event to happen again.

Discussion

The preliminary biodiversity database for HEPA is an evolving one. iNaturalist is a ‘live’ platform and the identification of species in the uploaded observations would continue to evolve with the involvement of more taxonomic identifiers from Vietnam and around the world. For example, the total number of identified species recorded from BioBlitz@HEPA could increase or decrease from 12 as more identifiers take part in identifying the observations and either agree or disagree with the identifications of other identifiers. Although the Singaporean project lead and the Vietnam planning team members were not taxonomic experts, developing such a preliminary biodiversity database for HEPA was possible because iNaturalist linked up with project with the global community of taxonomic identifiers. With the growing prevalence of mobile internet-associated technologies (Blaschke, 2012) including in rural areas, this shows that iNaturalist is a useful tool for developing local biodiversity databases.

As an educational activity, the BioBlitz@HEPA event was not able to completely reflect the range of fauna that can be found in HEPA (e.g. chameleons, squirrels, cobras, iguanas, pangolins, birds and nocturnal animals), because it had many participants and was conducted during the day. Nonetheless, the preliminary open-source database, with its geotagged photographic records of flora and fauna such as forest mushrooms and spiders, is a good start for HEPA. This database will be used to enrich the curriculum of HEPA’s environmental workshops and nature retreats for the younger generation.

Against the backdrop of an ongoing global pandemic, the positive feedback from all participants, especially regarding how their perception of nature was transformed, made the arduous organisational efforts all the more meaningful. The Vietnam planning team and the organisers felt that they were doing their part to avert future pandemics, by reinforcing in the rural Son Kim 1 community a love for nature. This is because protecting Earth’s fragile ecosystems has never been more urgent due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which is attributed to an imbalance between nature and mankind (UNEP, 2020). As the participants unanimously reflected, there is value to conducting similar nature appreciation events for the Son Kim 1 local community at HEPA again.

Conclusion

BioBlitz@HEPA took place on 2-3 January 2021 with the cooperation of the Son Kim 1 commune government, school teachers and other local area support staff. Through iNaturalist, the event kickstarted the systematic documentation of local biodiversity. A total of 103 observations were uploaded onto the event’s iNaturalist project page. With the contribution of the global community of scientists and taxonomic identifiers, 11 observations were research grade and a total of 12 species were identified. The event also increased the appreciation of nature amongst the 42 student participants from the commune’s primary and secondary schools, exposed local educators to a more effective pedagogy of learning through outdoor activities and amplified local stakeholders’ enthusiasm about Vietnam’s nature.

Communities in rural areas live close to nature, yet may not be the most well-resourced. Engaging their hearts will steer them towards daily decisions that are pro-nature, hence it is important to conduct more environmental and nature education for them. Particularly, the youth can be environmental advocates in their communities. Further investment and support are needed to engage rural communities on this agenda, for example by conducting more BioBlitz events. iNaturalist is a helpful tool to enable this.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the technical advice and iNaturalist support from Mr Carlos Velazco, the dedicated work from the staff at HEPA, and the advice on biodiversity survey methods from Mr Junhien Chong and Mr Raymond Karam. Heartfelt appreciation also goes to the principals and teachers of Son Kim 1 primary school and Son Kim secondary school, the leaders of Son Kim 1 commune in Huong Son district, Ha Tinh province, Vietnam. BioBlitz@HEPA was funded in part through a grant from the National Geographic Society.

REFERENCES

Aristeidou, M., Herodotou, C., Ballard, H. L., Young, A. N., Miller, A. E., Higgins, L., & Johnson, R. F. (2021). Exploring the participation of young citizen scientists in scientific research: The case of iNaturalist. Plos one, 16(1), e0245682.

BBC (2021). GCSE: Investigating ecosystems. Bitesize, BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zmxbkqt/revision/5 (Accessed: 19 February 2021)

Blaschke, L.M. (2012) Heutagogy and lifelong learning: A review of heutagogical practice and self-determined learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 13(1): 56-71.

Chandler, M., See, L., Copas, K., Bonde, A. M., López, B. C., Danielsen, F., Legind, J.L., Masinde, S., Miller-Rushing, A.J., Newman, G., Rosemartin, A. & Turak, E. (2017). Contribution of citizen science towards international biodiversity monitoring. Biological Conservation, 213, 280-294.

Chiutsi, S. and Saarinen, J. (2017) Local participation in transfrontier tourism: case of Sengwe community in Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area, Zimbabwe. Development Southern Africa, 34(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2016.1259987

Dickinson, J. L., Shirk, J., Bonter, D., Bonney, R., Crain, R. L., Martin, J., Phillips, T. & Purcell, K. (2012). The current state of citizen science as a tool for ecological research and public engagement. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 10(6), 291-297. (https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1890/110236)

Duckworth, J.W., Batters, G., Belant, J.L., Bennett, E.L., Brunner, J., Burton, J., Challender, D.W.S., Cowling, V., Duplaix, N., Harris, J.D., Hedges, S., Long, B., Mahood, S.P., McGowan, P.J.K., McShea, W.J., Oliver, W.L.R., Perkin, S., Rawson, B.M., Shepherd, C.R., Stuart, S.N., Talukdar, B.K., van Dijk, P.P., Vie, J-C., Walston, J.L., Whitten, T. and Wirth, R. (2012) Why Southeast Asian should be the world’s priority for averting imminent species extinctions, and a call to join a developing cross-institutional programme to tackle this urgent issue. Surveys and Perspectives Integrating Environment and Society, 5(2): 1327.

GBIF (2021). Free and open access to biodiversity data. Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). https://www.gbif.org/ (Accessed: 19 February 2021)

HEPA (2021). HEPA Farmer Field School. http://ecofarmingschool.org/eng/ (Accessed: 19 February 2021)

iNaturalist (2021a). https://www.inaturalist.org/ (Accessed: 19 February 2021)

iNaturalist (2021b). HEPA BioBlitz 2020 Nat Geo: Jan 2, 2021 – Jan 3, 20201. https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/hepa-bioblitz-2020-nat-geo?tab=observations (Accessed: 19 February 2021)

Mendez-Lopez, M.E., Garcia-Frapolli, E., Ruiz-Mallen, I., Porter-Bolland, L., Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.C. and Reyes-Garcia, V. (2018) Who participates in conservation initiatives? Case studies in six rural communities of Mexico. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2018.1462152

Neudert, R., Ganzhorn, J.U. and Watzold, F. (2016) Global benefits and local costs – the diliemma of tropical forest conservation: a review of the situation in Madagascar. Environmental Conservation, 44(1): 82-96.

NGS (2021a). Resource library – Encyclopaedic entry: citizen science. National Geographic Society. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/citizen-science/ (Accessed: 19 February 2021)

NGS (2021b) BioBlitz and iNaturalist. National Geographic Society. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/projects/bioblitz/ (Accessed: 19 August 2021)

Nugent, J. (2018) iNaturalist: Citizen science for 21st-century naturalists. Science Scope, 41(7): 12-13.

Sohdi, N.S., Koh, L.P., Brook, B.W. and Ng, P.K.L. (2004) Southeast Asian biodiversity: an impending disaster. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 19(12): 654-660.

Son Kim 1 commune (2021, 3 January). Học sinh trường THCS Sơn Kim và trường tiểu học Sơn Kim 1 trải nghiệm thực tế tại khu sinh thái Hepa. http://xasonkim1.hatinh.gov.vn/hoc-sinh-truong-thcs-son-kim-va-truong-tieu-hoc-son-kim-1-trai-nghiem-thuc-te-tai-khu-sinh-thai-hepa-nd,25128 (Accessed: 19 February 2021)

TAF (2017). Community Water Quality Monitoring: Biomonitoring Approach using Macroinvertebrates – training guide. The Asia Foundation – Laos, Vientiane, Lao PDR.

UNEP (2020, 31 March). COVID-19 and the nature trade-off paradigm. United Nations Environment Programme. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/covid-19-and-nature-trade-paradigm (Accessed: 19 February 2021)

Unger, S., Rollins, M., Tietz, A. and Dumais, H. (2020) iNaturalist as an engaging tool for identifying organisms in outdoor activities. Journal of Biological Education, https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2020.1739114

Vardi, R., Berger-Tal, O. and Roll, U. (2021) iNaturalist insights illuminate Covid-19 effects on large mammals in urban centres. Biological Conservation, 254: 108953.

Washington, H. (2018) A Sense of Wonder towards Nature: Healing the Planet through Belonging. Routledge.

Recent Comments