by Jason Banta

Peer writing, not peer review: a process oriented change using the Google Docs to meet the challenge of student engagement and revision in a COVID-19 learning environment

UTW2001P: Science Fiction and Empire

The switch from face-to-face to distance learning models in the middle of semester 2 of AY 2019-2020 required both proactive and efficient solutions to meet the learning objectives of UTW2000 courses. Fortunately, most of the seminar and classroom work for the course had been completed by the time that full switch to a distance learning model was made. The challenge then was to design a collaborative environment that gave the students the support they needed without overwhelming the lecturer. The switch to a distance learning model required instructors to balance the competing requirements of meeting learning objectives for courses designed for face-to-face interaction, with the need for increased student support due to the new learning environment.

I designed the collaborative environment with two guiding principles 1) minimal technology and 2) capitalization of student collaboration, both for their own benefit, but also to reduce the burden on the lecturer and allow me to focus my efforts where they would be most useful. Scholars have noted that technical limitations and difficulties are the greatest drawback of online peer review (OPR) activities (Chong, Goff, and Dej, 2012). To alleviate this as much as possible, I worked to reduce the actual technological intervention by relying only on one program. I also did not want to spend all my time merely editing student work, and instead concentrate on the higher-level content and critical thinking aspects of the writing projects.

Peer Review and Assessment in the UTW2000 modules: Peer assessment is a valuable tool for improving students’ general editing skills as well as encouraging autonomous learning practices. Benefits for the for the student receiving feedback are obvious (Van den Berg, Admiraal & Pilot, 2006). Studies have also shown that the reviewer gains valuable experience that helps her or his own editing skills, increasing the efficacy of their own work habits (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Carnell, 2015).

Module Requirements: For the UTW2000 modules, 10% of the student’s grade is determined by peer review activity. While each module has slightly different expressions of these activities, for UTW2001P, peer review is normally carried out in class, in small groups of 3 to 4 students, with supervision and intervention by the lecturer. This peer review activity focuses on the final research project. The final research project, a traditional research style paper (requiring a focused thesis and clear conceptual framework, a solid methodological orientation and sufficient evidence from a primary object to support the thesis) on a topic of the student’s choice (in this case a particular science fiction narrative that highlights postcolonial themes or concerns in a contemporary context). The students have been working on this project all semester starting with a bibliography creation activity for assignment 1 and a research pitch presentation for assignment 2. This paper compromises 40% of the final grade. Effective peer editing for this assignment can have a substantial impact of the student’s final grade.

Technology used: Google Docs.

Preparatory work: The students were divided into groups for this assignment. I usually divide the top performing students among different groups, and then used the similarity of the research projects to fill out the rest of group. This does run the risk of having the better students performing the bulk of the work. In the past, however, I have found that the increased work that some students do actually inspires other group members to work more. Regardless, even if the better students edit more thoughtfully and comprehensively, they benefit just as much due to practicing their editing and reading skills (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Carnell, 2015). In addition, by offloading much of the basic editorial work to peer activities, I have more time to monitor participation and intervene if there is a huge disparity in student work.

I worked to avoid grouping the same people from previous group exercises together. The first major writing assignment for the course was a collaborative paper and in the second assignment, the research pitch, students were assigned groups for their responding activities. The reason for continually changing the groups was to allow the students to experience a wider range of approaches, topics and writing styles form their peers, and to avoid editing fatigue from reading the same work repeatedly. Each group was then assigned a folder, as per image 1. This was done right after assignment 2 was completed and before any writing was expected to be done for paper 3.

Image 1

Initial Steps: The students were required to create documents in their folder, and use those documents as their work in progress draft of their paper (see image 2). They were encouraged to comment as their peers were writing. I also would drop by each folder (usually every few days over a 2 week period).

Image 2

Observations during the process: 80% of the students completed the assigned tasks. Of those 80%, I saw a significant increase in peer comment and peer engagement from traditional, in class peer editing work from students of all levels (from the better to the struggling).

- Of the groups where all 4 completed the requirements of the assignment, each paper was commented on by all the other group members. Sometimes in a classroom environment, especially with 4 person groups, this is not possible.

- On average, each student made 4.4 major comments on their peer’s paper (ranging from 1 – 10 comments). These comments were 3 sentences or more.

- When I did comment, I noticed that instead of shutting discussion, it usually encouraged the other group members to add their own thoughts, either clarifying what I commented on or offering suggestions as to how the writer could implement my requested changes.

- An interesting phenomenon I noticed was the emergence of the “Dr. Banta translator” student. I had a number of students who had taken my UTW1001P course, and they often offered advice that included phrases such as “when Dr. Banta says this he means….”.

- A small group of students, 5, from different groups, reached beyond their group and commented on other group papers, which then invited more cross commenting. This was especially helpful because it shored up those groups that had less than 100% participation.

- Of the comments that students made, major trends included: comments on clarity and use of vague language, suggestions for connecting the introduction and conclusions better, suggestions for clarification of terminology use (empire, power, control), help connecting frameworks to evidence, and suggestions of other sources for use in the research project.

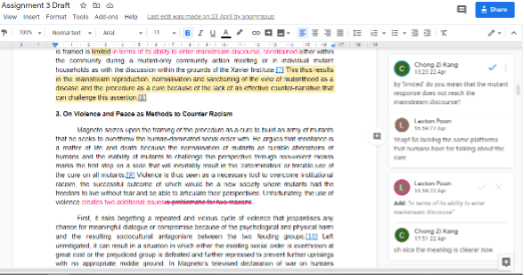

- Rather than just making the change and moving on, writers would often incorporate a suggestion and then add a comment asking what the editor thought of their change. While these comments were not followed up on every time, there was a substantial amount of the editor re-commenting and either complimenting the change or continuing a discussion on the initial edit. See image 3.

Image 3

Preliminary conclusions: This change was a great success. Looking at the anecdotal evidence, the assignment increased the density and quality of participation, kept the students on track in terms of a writing schedule, and produced stronger papers overall (which may explain the slightly elevated grade curve for my modules in that semester). As a lecturer, I felt that I had a connection to my students while they were writing, and I could throw out a lifeline for a struggling student and redirect any students who were going off track. This is not something I normally experienced during face-to-face classes, because the format I had in place usually intervened after a full draft. Due to the student enthusiasm in peer commenting, I felt that I could take a step back and look for larger issues, such as difficulties with understanding particularly complicated theories (such as posthumanism) and misuse of racially charged terms (such as hybridity). I could also focus my comments helping the students raise the overall caliber of their paper, rather than working on making sure they were merely fulfilling the requirements. I did not feel compelled to micro-manage every group.

Changes and problems: The major issue was the lack of complete participation. Of course those students who did not upload their papers on time or at all are often the ones struggling the most. For the upcoming semester I plan to address this in two major ways: 1) use this arrangement from the start, so by the time the students get their final writing assignment, they will be acclimated to the process, and 2) clearly stipulate how much of this activity is reflected in their Peer Review (10%) grade.

References

Carnell, B. (2016). Aiming for autonomy: Formative peer assessment in a final-year undergraduate course. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(8), 1269-1283.

Chong, M., Goff, L. & Dej, K. (2012). Undergraduate essay writing: Online and face-to-face peer reviews. From here to the horizon: Diversity and inclusive practice in Higher Education, 5, 69-74.

Nicol, D. J. & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199-218.

Van den Berg, I., Admiraal, W. & Pilot, A. (2006). Design principles and outcomes of peer assessment in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 31(3), 341-356.