This is a longer version of an article that appeared in The Straits Times on 16 November 2016. To read the article, click here.

By Jenő Doby [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In the 1840s, the Hungarian physician, Ignaz Semmelweis, made a startling observation: women giving birth at his hospital’s maternity clinic were five times more likely to die from infections if they were cared for by doctors rather than by midwives. He hypothesised that doctors often performed autopsies before attending to pregnant mothers, resulting in a high risk of cross-infection. By making doctors in the clinic wash their hands, he showed that maternal deaths could be drastically reduced. The simple lesson was this: we should maintain good hand hygiene not simply for our own benefit, but to avoid harm to others.

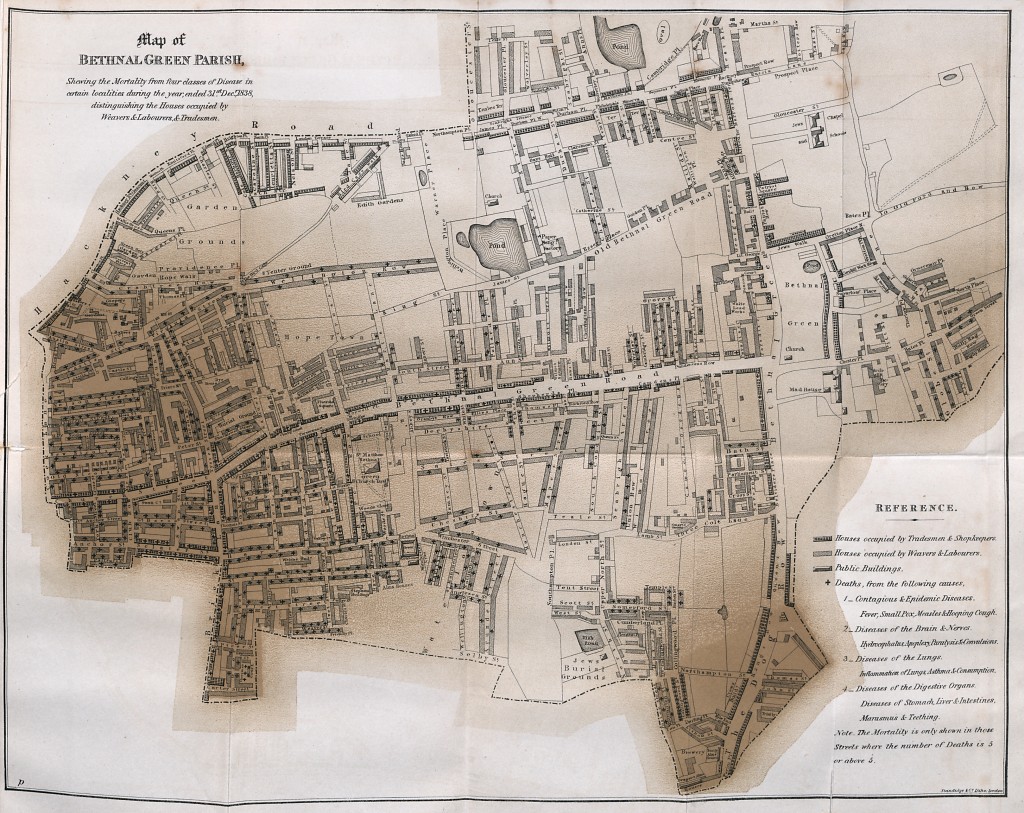

The history of public health is full of such salutary lessons. In the mid-19th century, while the scientific community debated whether diseases were caused by microscopic organisms or foul-smelling airs, the British reformer, Edwin Chadwick, showed that regardless of the mechanism, unsanitary living and working conditions were intrinsically linked to worse health and lower life expectancy. The sanitary reforms that followed resulted in vast health improvements in Britain in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Map of Bethnal Green Parish from Chadwick’s “Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain”. The map shows that many more deaths occurred in the crowded, poor homes of the labourers, relating classes of housing to disease. (In: Poor Law Commissioners’ Report on an Inquiry into the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain; London: W. Clowes and Sons, 1842)

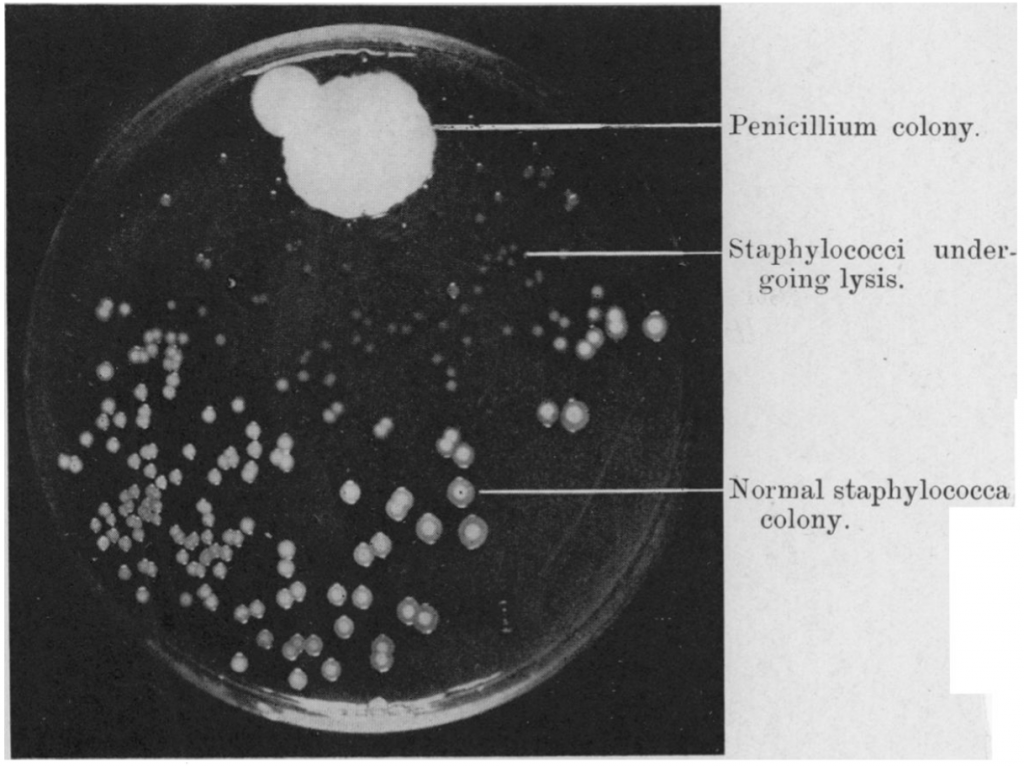

But in 1928, Alexander Fleming made a revolutionary discovery. A mold that had accidentally contaminated bacterial cultures in his laboratory produced a substance that killed the bacteria. And so, the antibiotic era was born. Since their discovery, antibiotics have revolutionised medical practice and public health. Infections that once killed could be treated with a simple course of penicillin. More complex medical procedures that make the body vulnerable to infections, such as open surgery, chemotherapy and transplantation, were made possible by antibiotics to prevent or treat these infections. And the day was foreseen when infectious diseases would no longer be a scourge on humanity.

Photograph of a culture plate showing the dissolution of staphylococcal colonies in the neighbourhood of a penicillium colony (A.Fleming, British Journal of Experimental Pathology, Vol X, No. 3, 1929).

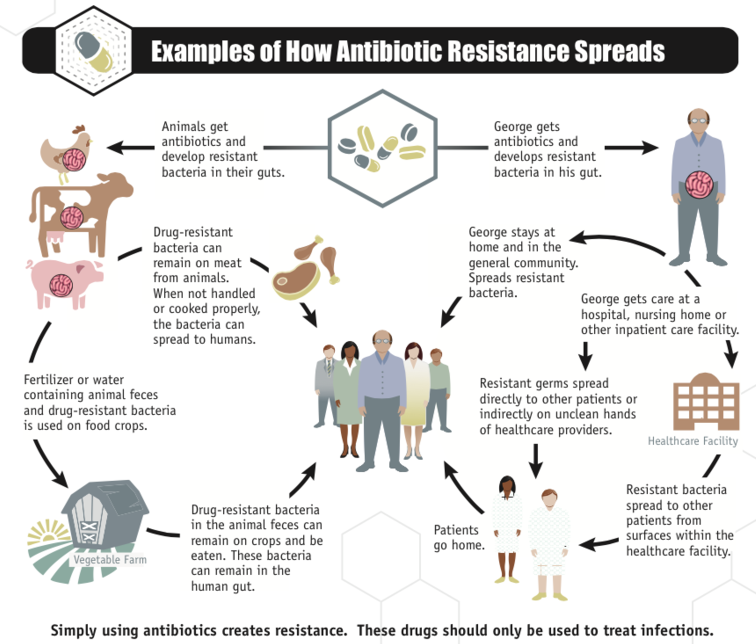

The evolution of resistance is a natural phenomenon innate to the survival of bacteria and other microbes, but the problem of antimicrobial resistance is man-made, a result of large scale over-use and misuse of antimicrobial drugs, especially antibiotics. More than half of all antibiotics are used in the agricultural sector and of these, about 70 percent are antibiotic classes that are important for human medical use. Antibiotics have become so cheap and widespread that large sectors of the agricultural industry can afford to mass treat entire fish farms and herds of pigs, poultry and cattle to promote faster growth or prevent infection in food animals. The high densities in which food animals are increasingly reared to meet global demand for animal protein would not be possible without using antibiotics.

Image credit: www.id-ea.org

The economic benefits to agricultural producers of using antibiotics for growth promotion and disease prevention are substantial, but the health and societal consequences are disastrous. Evidence of resistant bacteria emerging from antibiotic use in food animals is growing. Scientific studies increasingly show that alarming levels of antibiotics are leaked into the environment from agriculture and pharmaceutical production, creating ideal conditions for bacteria to exchange genetic material that allows them to become resistant to antibiotics. Such irresponsible use of antibiotics not only poses a risk to those in contact with animals, but also to consumers of contaminated meat products and the wider public.

Image credit: CDC

At the same time, over-prescription and misuse of antibiotics in human and veterinary medicine has led to a rise in so-called superbugs. Around 80% of antibiotics used in human medicine are prescribed in ambulatory and primary care. Studies suggest that about half of these are used to treat infections for which antibiotics are ineffective, such as colds and flu, or to treat infections that are already resistant to these antibiotics. Often, these infections are treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics that target a wide range of bacteria. But inappropriate use of broad-spectrum antibiotics also serves to promote resistance in a wide range of bacterial species, making things worse in the long run. Killing off the susceptible bacteria helps bacteria resistant to those antibiotics to survive and multiply without competition. And because resistant bacteria can be transmitted between people even if they have no symptoms, over time our existing arsenal of antibiotics becomes less and less effective for treating patients who really need them. Doctors are increasingly encountering patients with infections that are untreatable, or treatable only with last-resort drugs that are both more costly and more toxic.

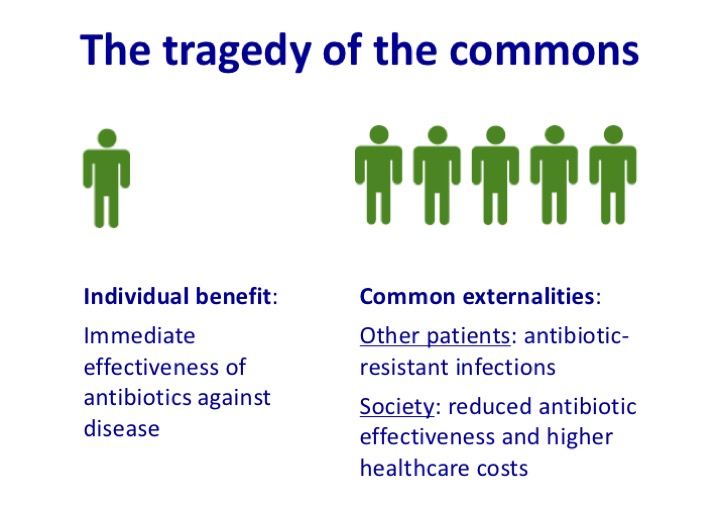

Antibiotic resistance is a classic example of what economists call the tragedy of the commons: while we can all benefit from appropriate use of antibiotics, the harmful consequences of antibiotic misuse, in the form of resistant infections, tend to fall on others. As a result, we have little incentive to use antibiotics cautiously. But the more we all use antibiotics, the worse off we all are as a society. And because antibiotics are used for short periods, they are less profitable than other drugs, creating a financial disincentive for pharmaceutical companies to invest in antibiotic discovery – no new class of antibiotics has been developed for the past thirty years.

The problem of antimicrobial resistance is so urgent that it was specifically singled out for discussion at the United Nations General Assembly meeting in New York last month, only the fourth time a health-related issue has been discussed in that forum. The resulting declaration was heartening, an affirmation by world leaders to tackle antimicrobial resistance, by committing to strengthening monitoring of the problem, preventing infection through immunisation and improved sanitation, encouraging the development of diagnostics to determine when antibiotics are appropriate, creating viable economic models for the development of new antibiotics, reducing overuse of antibiotics in humans and animals while improving access for those who need them most, and enhancing education and communication on prudent antibiotic use.

This list underlines the breadth and scale of the challenge. It is also a reminder that in public health there are no silver bullets. Over the past century, we have gradually lost sight of this fact, while becoming increasingly focused on a predominantly technological and biomedical view of health and disease. Our narrow focus and misplaced hope in magic fixes has led to an isolation of public health from other areas of public policy, resulting in policies that are often disjointed and contradictory. We allow the food industry to make products laden with sugar and fat derived from heavily subsidised agricultural practices, but then tax them for selling these products; we require workers to work longer hours, but recommend that they stand at their desks while doing so; we tell children they must study harder and be IT literate in order to succeed, but lament the health effects of too much screen time and not enough time spent outdoors; we have strict requirements for the licensing and use of pharmaceutical products, but make ‘natural’ remedies and supplements with no proven medical benefit widely available with little regulation.

Disjointed policies will not work for a problem as complex as antimicrobial resistance. To tackle this problem, we need to re-think how we as a society organise and mobilise our institutions to address global challenges, safeguard the health of current and future generations and ensure that the health advances of the past century are not undone. The UN declaration is a welcome step, but we should not simply rely on governments or the scientific community to act. An effective response will require coordination between national institutions, international governments and the private sector, it will require sustained investments in sanitation and health systems, and it will take decades of research and implementation.

But you can act now. You can help to reduce our demand for antibiotics by pledging to take a few key steps. You can reduce your own and others’ risk of infections by keeping up to date with vaccinations and maintaining good hand hygiene. You can demand better information about how the food you eat is produced, and you can choose to reduce consumption and demand for animal products produced using irresponsible practices. You can demand more action to improve hygiene and infection control practices to prevent transmission of antibiotic resistant bacteria and other infections in our hospitals and healthcare institutions, which have a responsibility to safeguard our health. And you can choose to use antibiotics responsibly by acting on public health’s salutary lessons. The next time you experience a minor ailment, you can question whether you really need a course of antibiotics, not simply because it might not do you any good, but because it could prevent doing harm to others.

By Clarence Tam