Hsu Li Yang is Associate Professor at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, where he leads the Antimicrobial Resistance Programme. In the first of a series of blog posts for World Antibiotic Awareness Week, he talks about the progress and challenges of controlling MRSA in Singaporean hospitals.

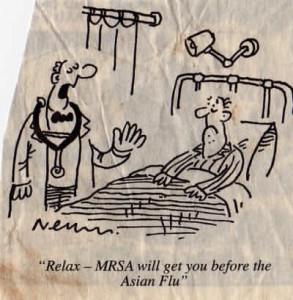

I was asked to write a blog post about antimicrobial resistance in Singapore for World Antibiotic Awareness Week 2016 and I wondered what I could write without repeating previous posts and articles ad nauseam, including those written by the current head of the Department of Microbiology at Singapore General Hospital (http://10minus6cosm.tumblr.com/). In the end, I came to the conclusion that it did not really matter – some things deserve to be repeated ad nauseam until change happens. I have put together a narrative on one of the better-known drug-resistant bacteria: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

We do not really know when MRSA first appeared in Singapore, and whether the first MRSA isolates were imported or indigenous. Many will recall that MRSA was first discovered by the late bacteriologist Prof Patricia Jevons at Colindale Laboratory in UK in 1960. By 1979, almost 19% of all S. aureus isolated at the Department of Pathology – at that time the only microbiology laboratory in Singapore – were classified as “methicillin-resistant”. But it was only in the early 1990’s that MRSA became a cause for public concern here. In 1991, the country’s first infectious diseases physician Dr David Allen (the term “foreign talent” did not exist then, but he was invited to Singapore to establish infectious diseases as a medical specialty) and a local microbiologist Dr Mavis Yeo had both warned that MRSA was spreading rapidly in our hospitals. In February 1993, The Straits Times published a report of an MRSA outbreak at the Singapore General Hospital, stating among other things that “21 died from infection picked up in hospital”. In a follow-up piece 5 days later, the newspaper reported that “people had checked out and cancelled operations overnight”.

That led to multiple activities in local hospitals – mostly uncoordinated – to bring MRSA under control. And for a large part, these failed to do so. With a more modern understanding of MRSA transmission and how hospital systems work, it is easy to understand why. The science of infection prevention was in its infancy in Singapore then, and local experts believed that patients with MRSA-infected open wounds or MRSA pneumonia were more likely to spread the bug to others – these patients were isolated while others with MRSA colonization or other forms of infection were not. There was also little attempt to find patients with MRSA colonization (what we call “active surveillance” currently), who comprised the majority of patients with MRSA. Community hospitals and nursing homes also refused to accept MRSA-infected patients from the acute care hospitals (the patients had to have documented clearance of MRSA in the form of negative wound or nasal swabs), leading to many patients being stuck in the acute care hospitals. In the end, the Ministry of Health had to step in to compel nursing homes and community hospitals to accept MRSA-infected patients, and MRSA control efforts in hospitals waned (or at least did not progress) by the end of the 1990s.

A second intensification of MRSA control efforts in local hospitals occurred from 2006 onwards. I am not sure why this happened, but perhaps it was a confluence of several events, including:

- Having a new generation of infection prevention experts in Singapore (many of whom had not experienced the failure of the 1990s).

- More coverage on MRSA in both The Straits Times and other newspapers.

- Perhaps even the success of UK in controlling MRSA as a result of the then Labour Government’s commitment to reduce MRSA rates in UK hospitals by 50% in the course of an election cycle.

This time, many of the mistakes of the past decade were avoided. There were multiple efforts aimed at increasing that most basic and important infection prevention measure – hand hygiene. Most hospitals also initiated “active surveillance” to detect and isolate/cohort the huge reservoir of asymptomatic MRSA-colonized patients, implementing these in steps in order to ensure that there was sufficient laboratory capability and isolation/cohort facilities (because there is a paucity of isolation rooms in local hospitals and a significant number of patients with various drug-resistant bacteria, patients with the same drug-resistant bacteria are commonly placed together in 4- to 8-bed cubicles).

Coincidentally, antimicrobial stewardship programmes were also implemented in many local hospitals after 2008, in order to reduce the inappropriate prescription of broad-spectrum antibiotics. However, it is unlikely that this played a direct role in the control of MRSA.

And the good news is that MRSA rates started to fall in 2008, and have continued to dip in the 8 years since, although the rate of decline has slowed in recent years. We have not achieved the standards of the northern European countries (where hospital-associated MRSA has virtually been eliminated) or West Australia, and still lag behind the UK considerably. Will we ever get there? At current projections and technology, and understanding local limitations, the answer is no. Our hospitals remain congested with high bed occupancy rates, which has knock-on effects on the practice of hand hygiene and the ability to isolate/cohort MRSA-infected patients. The rise and spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CREs) also introduced a “competitor” for both scarce isolation/cohort resources in local hospitals, and the attention of healthcare staff. More resources or process/technology breakthroughs are required in order to attain what the northern European hospitals have achieved for decades.